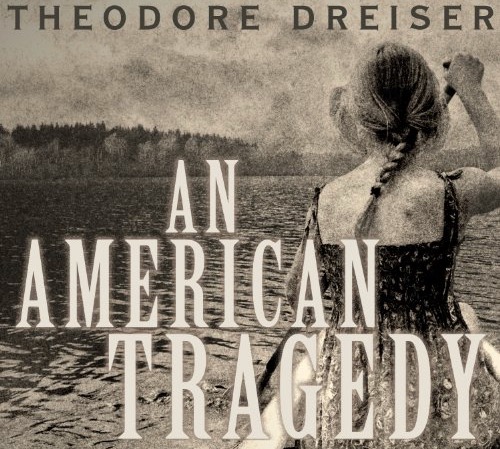

An American Tragedy

Theodore Dreiser (1925)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Tennyson-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’77’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Does anybody really read Dreiser anymore? I remember being rather unimpressed by The Financier in my course in “American Realism and Naturalism” back around 1970. And I did try Sister Carrie decades later but it left me pretty cold. Nevertheless, in my undaunted quest to read all the books on Modern Library’s list of the “100 Best English Language Novels of the Twentieth Century,” there’s no escaping Dreiser’s gargantuan An American Tragedy, sitting there insistently at number 16.

Dreiser has never been admired for his style. In fact, even his greatest supporters, like H.L. Mencken, lampooned passages of his prose, and the influential literary scholar F.R. Leavis famously wrote that Dreiser “seems as though he learned English from a newspaper. He gives the feeling that he doesn’t have any native language.” With these caveats in mind, and hence daunted (and who wouldn’t be) by this novel’s mammoth 940 pages, I chose the perhaps even more masochistic route of listening to the book on Audible—itself a 36-hour ultra-marathon.

Verbosity is Dreiser’s other problem. It’s hard to imagine that this novel would not have been more effective if it were half as long. Every minute detail about every moment of our poor protagonist Clyde Griffith’s life is really not necessary, Teddy!

But where Dreiser excels is in the larger picture—plot, theme, and character. And his hyperattention to detail is explicable when you consider the movement he was a part of. Dreiser was a naturalist writer, spawned by Darwinism and refined by Zola, who saw human beings’ actions as determined by the irresistible forces of heredity and environment. So it was necessary to describe Clyde’s family in great detail, and dwell at length on his early experiences in work and in love, to understand why he turned out the way he did.

Born and raised in poverty in Kansas City and shaped by the puritanical fundamentalist preaching of his uneducated street-preacher father and sincere, mission-oriented mother, Clyde is ill-equipped for the economic realities of the adult world. But with his ambition and drive for both economic success and the romantic conquests forbidden him by the strict constraints of his family, Clyde finds some success as a bellboy in a Kansas City hotel. After he is involved in a fatal accident that leaves a child dead, however, he flees to Chicago and works under an assumed name. A chance encounter with his father’s brother, a successful manufacturer from upstate New York, results in an invitation to take a job at the uncle’s factory. By this time, however, to naturalist Dreiser, Clyde’s character is already inescapably formed by the deterministic forces of the universe: he will always evade personal responsibility if he possibly can, and he will make irrational decisions when faced with a crisis. In a Shakespearean tragedy, these traits constitute his tragic flaw.

Mesmerized by the wealth and the social position his uncle’s family holds, Clyde is irresistibly drawn to the lifestyle of the moneyed class. Attracted to Roberta Alden, one of the employees in the department he manages in his uncle’s firm, he begins a secret relationship with her (secret because romantic involvement with employees is strictly forbidden at his job), Clyde at the same time begins running with the rich crowd of young people in town, who accept him despite his poverty because he is Sam Griffith’s nephew. And he becomes completely enamored of the wealthy socialite Sondra Finchley. Wanting nothing more to do with the working-class Roberta, Clyde focuses on Sondra, but his plans hit a serious stumbling block with the news that Roberta is pregnant.

It’s only at this point that Dreiser gets to the heart of the story. Clyde tries to find a way to end Roberta’s pregnancy, but everything proves unsuccessful. Forty-eight years before Roe v. Wade, there’s no legal way out of this mess. Roberta insists on Clyde’s marrying her, or she will destroy his reputation and lose him his job. Meanwhile Clyde believes he will be able to marry Sondra, despite her family’s objections to his low class, when she comes of age in a few months. He just needs to get out from under the problem of Roberta. And after a good deal of planning, Clyde believes he has the solution. Go with her on a supposed wedding/honeymoon trip to the Adirondacks, go out on a boat on a deserted lake, and tip her in the water. He knows she can’t swim.

Nearly twenty years earlier, Dreiser had read sensational newspaper accounts of the notorious case of Chester E. Gillette. Resort owners in upstate New York found an overturned boat and the body of a young pregnant girl, Grace Brown, in the water at Big Moose Lake. Gillette was arrested soon after, and tried for murder. He claimed the girl’s death had been a suicide, but he was convicted, and the trial drew international attention when Grace’s love letters to him were read aloud in court. Gillette died in the electric chair on March 28, 1908. Dreiser was fascinated by the case, and for more than fifteen years saved the newspaper clippings, and after a few false starts finally completed his mammoth masterpiece in 1925.

Reading the text now, nearly a century later, one is struck by the constraints that combined to place such a tightening net around Clyde—the strictures that prevented any kind of safe and legal termination of the pregnancy, the puritanical and patriarchal rules about his dating a woman from his department, neither of which would have doomed him in a contemporary setting. Add to that the lack of Miranda rights that allowed the politically-motivated sheriff to question him with no lawyer present, the denial of a change of venue for the trial when he’d already been tried and convicted in the press and it was impossible for objective jurors to be found in the county, the prejudicial reading of the love letters, which had nothing to do with evidence and served only to cast him in an unfavorable light, even the prosecution’s planting of evidence, and you have what amounts to a wholesale skewering of the criminal justice system in the U.S. at that time. And this is not even taking into account the clear prejudice revealed in the makeup of the death row inmates (all foreigners, blacks, or working class poor), and the tragic execution of the penitent Clyde, which serves as as good an argument against the justice or efficacy of the death penalty as any I’ve seen.

But these things were not even the chief targets of Dreiser’s novel. When the book was made into a major film in 1931, Dreiser was appalled at what they had done to his story. The movie focused on society’s hypocritical attitude toward sex as Clyde’s downfall, but Dreiser, (a socialist, like many of his fellow writers of the Progressive era) was aiming his criticism at capitalist society and fundamentalist religion. Clyde is not the least bit admirable, but we identify with him through most of the novel because, like us, he is pursuit of the promise of a better—because wealthier—lifestyle. Thus he is a “representative” American, and so a candidate for a traditional tragedy. In any case, Clyde’s tragedy is a specifically “American” one because what draws Clyde to his fall is the seduction of wealth. Inspired by the “American dream” of rising from poverty to great wealth—at a time, like ours, when the gap between rich and poor in America was as wide as at any time in history—Clyde comes to believe that money is the Greatest Good, and therefore anything done in its pursuit is justifiable. That’s his tragedy. And, Dreiser implies, it is America’s.

NOW AVAILABLE

To the Great Deep, the sixth and final novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at http://encirclepub.com/product/to-the-great-deep/

You can also order from Amazon (a Kindle edition is available) at https://www.amazon.com/Jay-Ruud/e/B001JS9L1Q?ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_1&qid=1594229242&sr=8-1

Here’s what the book is about:

When Sir Agravain leads a dozen knights to arrest Lancelot in the queen’s chamber, he kills them all in his own defense-all except the villainous Mordred, who pushes the king to make war on the escaped Lancelot, and to burn the queen for treason. On the morning of the queen’s execution, Lancelot leads an army of his supporters to scatter King Arthur’s knights and rescue Guinevere from the flames, leaving several of Arthur’s knights dead in their wake, including Sir Gawain’s favorite brother Gareth. Gawain, chief of what is left of the Round Table knights, insists that the king besiege Lancelot and Guinevere at the castle of Joyous Gard, goading Lancelot to come and fight him in single combat.

However, Merlin, examining the bodies on the battlefield, realizes that Gareth and three other knights were killed not by Lancelot’s mounted army but by someone on the ground who attacked them from behind during the melee. Once again it is up to Merlin and Gildas to find the real killer of Sir Gareth before Arthur’s reign is brought down completely by the warring knights, and by the machinations of Mordred, who has been left behind to rule in the king’s stead.