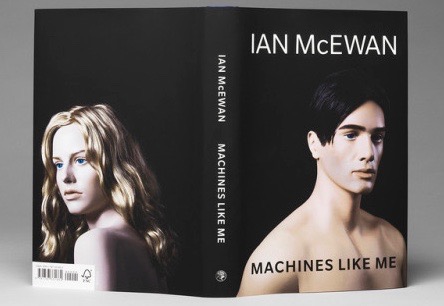

Machines Like Me

Ian McEwan (2019)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/3-12.jpg’ attachment=313′ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Three Tennysons/Half Shakespeare[/av_image]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Ian McEwan’s most recent novel is a departure from his usually realistic, historically-based narratives. Of course, his last novel, Nutshell (2016), was also a departure, being as it was a new twist on the Hamlet story told from the perspective of a fetus. But in Machines Like Me, McEwan enters the realm of alternative history, a genre more commonly associated with science fiction writers, like Philip K. Dick in his 1962 novel The Man in the High Tower (in which it is imagined that the Axis powers won World War II), but which more recently has been used in more mainstream novels like Vladimir Nabokov’s Ada (in which North America was partially settled by Tsarist Russia), Kingsley Amis’s The Alteration (in which the Protestant Reformation never took place), Phillip Roth’s The Plot Against America (in which pro-fascist Charles Lindbergh won the 1940 U.S. election), or Michael Chabon’s The Yiddish Policeman’s Union (in which there is no State of Israel, but many Jews live in an area of Alaska set aside for them by the U.S government).

In this novel, McEwan puts his own spin on the genre with a novel set in a London of 1982, the London of Margaret Thatcher, in which the British navy sets off to fight a war in the Falkland Islands which, in the first jarring clue that the novel is alternative history, turns into a devastating defeat for Britain, crushed by Argentina, which annexes the islands and changes their name to Las Malvinas. The defeat drives Mrs. Thatcher from office, resulting in the rise of a populist Labour candidate and a movement to separate from the European Union—nearly forty years in advance of Brexit.

But these events play a relatively minor role in the novel’s alternative history. For McEwan’s chief question in the book is, what would have happened if the brilliant computer scientist Alan Turing hadn’t committed suicide in 1954?

Turing, best known to the general public as Benedict Cumberbatch in the 2014 film The Imitation Game, was, as that film makes clear, instrumental in developing a prototypical computer during World War II that could discover the settings of the Germans’ Enigma machine, thereby cracking intercepted coded Nazi messages that made it possible for the allies to win the war. The acknowledged father of theoretical computer science, a mathematical genius who was a pioneer in the development of artificial intelligence, Turing ultimately developed what has become known as the “Turing test”: for a machine to be deemed “intelligent,” that is, capable of actual “thought,” Turing suggested, it would have to be impossible for a human interrogator to tell the difference between the machine and another human through conversation.

Just how far the development of computer science and artificial intelligence might have come, or what direction it might have taken, if Turing had lived, is impossible to determine. But he did not live. In 1952, Turing was convicted of what the British law called “gross indecency” because of his sexual orientation, and he was given the choice of going to prison or submitting to a year of what was called “chemical castration.” He was given the drug diethylstilbestrol, which rendered him impotent and caused breast tissue to form. A year later he died by his own hand through cyanide poisoning. He was 41.

In McEwan’s alternate history, Turing chose prison rather than sterilization, and went on to continue the advances in computer science and artificial intelligence he was making. He appears in the novel himself, as a kind of chorus figure. As a result of his continued work, the world achieves an information revolution decades before it reached that stage in actual history. There are electric cars that drive themselves. There is a surprisingly advanced version of the Internet that allows day trading online. And, most important for this novel, there are artificial human beings, androids, who can be ordered, delivered to your house, and programmed with personality traits that you choose for them.

At this stage, admittedly, they are only prototypes. There are twenty-five of them: thirteen males or “Adams,” and twelve females or “Eves.” The novel’s protagonist, Charlie Friend, is a thirty-two-year-old man-child who ironically seems to have no “friends” of his own. He’s a one-time computer whiz who studied physics and anthropology in school but seems never to have held down a steady job, but rather invested in a number of failed get-rich-quick schemes and seems to have barely escaped prison for tax fraud. Now he spends his days in his two-room flat in south London, playing the stock market on his home computer with just enough success to scrape by. But when the new artificial humans come on the market, computer nerd Charlie spends his whole inheritance from his mother, £86,000, on a brand new Adam. He had really wanted an Eve, but they’d all been snapped up already.

But Charlie doesn’t just love robots; he’s also enamored of his upstairs neighbor Miranda. Ten years his junior, she is a graduate student of history, and is the daughter of a famous but reclusive writer. Part of his courting of Miranda consists of Charlie’s allowing her to choose half of Adam’s traits that can be programed into him. In a way, Adam becomes a kind of surrogate child for the two of them as they form a pseudo-family. This becomes complicated when the now totally functional Adam, conversant with computerized data from all over the 1980s Internet, warns Charlie that Miranda is not completely truthful and is hiding a dark secret; more complicated when, after an argument with Charlie, Miranda takes the anatomically correct Adam to bed and the artificial man develops “feelings” for his mistress; and even more complicated still when Miranda, no longer content with her artificial offspring with Charlie, becomes intent on adopting an abused young “real” boy named Mark.

I don’t want to go further since I don’t want to spoil any of the later plot developments for you. And indeed, some reviewers have seen the plot as less unified than they would like. Some have also criticized the world McEwan creates here as not fundamentally different enough from our own to be acceptable as alternate history. Frankly, it seems to me these complaints fall into the trap of criticizing the book for not being the book those critics would have written if they had written the book. Thematically, the novel seems to me perfectly unified. It is, first of all, a representation of a being who passes “Turing’s test” brilliantly: there is a tour de force demonstration of that in a scene when Charlie and Adam visit Miranda’s father, and after their conversation he concludes that Charlie is the robot.

But beyond that the book also explores to a great extent the differences between human and artificial intelligence. One disturbing aspect of the story is that a rash of suicides begins among the artificial humans, as if for some reason they can no longer face a world governed by human beings. Adam, for good or ill, makes his decisions based on assembling all the facts and coming to the most logical conclusions from them. Truth is to him of foremost importance. When it comes to Miranda’s “dark secret,” which involves a moral decision she made which she believes to be justified and ethical even though it involves lying, Adam cannot see it. And far from being a servant, he ultimately takes matters into his own hands, first by overriding his off switch (an act McEwan refers to, in an allusion to Paradise Lost, as his “first disobedience”), and later by making independent moral decisions without consulting his “masters.”

These questions of moral relativity are set against a backdrop of a world full of fairly arbitrary differences from our own—a world where Jimmy Carter was elected to a second term and Ronald Reagan never became president, where the Beatles were reunited in 1982, and in which it turns out JFK was not assassinated after all—but one in which human nature has not changed at all, and everyday life, despite the technological advances, is much the same as it is in our world. Brexit, after all, still occurs. It’s the contrast between that indelible human nature and the artificial intelligence of an Adam that this book is about. Three Tennysons and half a Shakespeare for this one.

NOW AVAILABLE:

The Knight of the Cart, fifth novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at https://encirclepub.com/product/theknightofthecart/

You can also order from Amazon at

https://www.amazon.com/Knight-Cart-MERLIN-MYS…/…/ref=sr_1_1…

OR an electronic version from Barnes and Noble at

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-knight-of-…/1133349679…

Here’s what the book is about:

The embittered Sir Meliagaunt is overlooked by King Arthur when a group of new knights, including Gildas of Cornwall, are appointed to the Round Table. In an ill-conceived attempt to catch Arthur’s notice, Meliagaunt kidnaps Queen Guinevere and much of her household from a spring picnic and carries them off to his fortified castle of Gorre, hoping to force one of Arthur’s greatest knights to fight him in order to rescue the queen. Sir Lancelot follows the kidnappers, and when his horse is shot from under him, he risks his reputation when he pursues them in a cart used for transporting prisoners. But after Meliagaunt accuses the queen of adultery and demands a trial by combat to prove his charge, Lancelot, too, disappears, and Merlin and the newly-knighted Sir Gildas are called into action to find Lancelot and bring him back to Camelot in time to save the queen from the stake. Now Gildas finds himself locked in a life-and-death battle to save Lancelot and the young girl Guinevere has chosen for his bride.