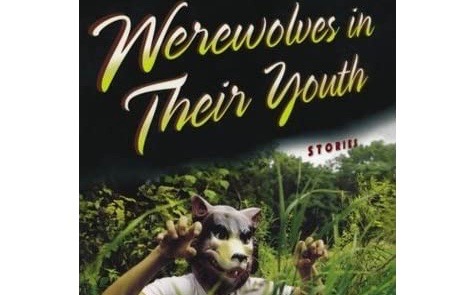

Werewolves in Their Youth

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Tennyson-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’77’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Michael Chabon (1999)

I freely confess to being a Michael Chabon completist, at least as far as his fiction goes. Ever since reading his 2001 Pulitzer Prize-winning Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, I have aspired to read every novel and short story Chabon ever wrote, from his acclaimed first novel The Mysteries of Pittsburgh (1988) through his most recent semi-fictional novel about his grandfather, Moonglow (2016). The list includes two collections of short stories: A Model World and Other Stories (1991) and this one, with the promising title Werewolves in Their Youth. With Werewolves, I have completed this self-imposed task—at least temporarily, until Chabon’s current fictional project (purported to be a sequel to his 2002 YA novel Summerland) is published. One general truth I’ve observed in all of this reading, which pertains to the book under discussion here, is that Chabon’s novels tend to be far more impressive than his short stories.

I’m probably not the first of Chabon’s sympathetic readers to think this, and I’m certainly not the first to put it in writing. In 2003, Chabon was guest editor for McSweeney’s Mammoth Treasury of Thrilling Tales, and in the editor’s preface to that collection he lamented—humorously but not insincerely—that the short story in English, as practiced for some fifty years, was almost exclusively “the contemporary, quotidian, plotless, moment-of-truth revelatory story.” Most readers, he suggested, were bored by this. And, he added, “I am that bored reader, in that circumscribed world, laying aside his book with a sigh: only the book is my own, and it is filled with my own short stories, plotless and sparkling with epiphanic dew.” He seems to have been referring to his own (at that time) recent collection, Werewolves in Their Youth: nine stories, the first eight of which follow the sort of Joycean pattern he suggests in this comment. Chabon was making an argument for genre fiction in his editorial comments for McSweeney’s, an argument for science fiction or mystery or horror (the American short story was fathered, after all, by Poe), and in the final story of Werewolves, Chabon breaks out of his slavish homage to Joyce and provides a macabre homage, instead, to H.P. Lovecraft.

That final story, “In the Black Mill,” actually purports to be written not by Chabon himself but rather by August Van Zorn, whose name readers of Chabon’s Wonder Boys (1995) will recognize as the pulp fiction writer who, as a boarder in his grandmother’s hotel, served as a kind of role model for the young Grady Tripp, the protagonist of that novel: Van Zorn wrote horror stories at night ‘”in a bentwood rocking chair…a bottle of bourbon on the table before him”—until his ultimate suicide. He’s the model of the old plot-driven genre writer who cranks out one story after another while Grady spends seven years writing an unpublishable novel thousands of pages in length. In a move reminiscent of Kurt Vonnegut’s use of his imaginary science-fiction author Kilgore Trout, it’s Van Zorn Chabon turns to as the supposed author of the very Lovecraft-esque “In the Black Mill.”

This story, set in the Yuggogheny Hills near Chabon’s native Pittsburgh, involves an archeologist who, researching the former Native American residents around the town of Plunkettsburg, begins to take an interest in the history of the local Plunkettsburg Mill, wondering why so many of the men who work at the Mill are missing parts of their bodies: here a finger, there an ear, even perhaps a foot. What exactly do they manufacture in this Mill? No one ever seems to be able to tell him. He tries at one point to enter the Mill, passing as a laborer, but is thrown out before he can get inside. The feeling that something sinister is going on in that place becomes stronger and stronger, and the narrator needs to drown his apprehensions by indulging in the local beer, “Indian Ring.” The horrifying denouement is everything you’d want in this particular sort of genre thriller.

There is a kind of Gothic vibe that unifies all the stories in the collection, though in all but the last it is more figurative than real. The title story, which begins the volume, focuses on two schoolboys, Paul and Timothy, the latter of whom consistently says he is a werewolf. Paul tries to dissociate himself from his friend, who is too weird for anyone else in the class, and Timothy ends up attacking another student and gets sent to a special school. In “House Hunting,” a young quarreling couple is shown a house by a drunken realtor who keeps pocketing random items as they go through the house. In “Son of the Wolfman,” a couple who have unsuccessfully tried everything to have a child is rocked when the woman is raped and becomes pregnant. In “The Harris Fetko Story,” a professional football player is estranged from his father and former coach, now remarried, and has to decide whether to attend the bris for his new half-brother. And in one of the most successful stories, “Mrs. Box,” a young bankrupt optometrist with $20,000 worth of equipment in his trunk is fleeing town to get away from his failed business and his failed marriage, when on a whim he decides to visit his ex-wife’s elderly grandmother only to find that she’s lost her short-term memory, and he decides to rob her.

Each story has a kind of monster, a kind of extreme character whose behavior is beyond everyday classification. A “werewolf” as it were. The stories are also united by the recurring theme of failed marriage or other significant relationship, and by the conventional “epiphany” ending that often restores a relationship or brings a flash of insight to the protagonist: In other words, the kind of story Chabon deprecated in his McSweeney’s foreword. But the collection is not so very disappointing: Chabon’s insightful and vivid prose, what critics have called his “perfectly self-contained” and “finely crafted” sentences, still sparkles in these stories. Marriage, he writes in what could describe the whole collection, is “at once a container for the madness between men and women and a fragile hedge against it.” Of our football player he says “Inside Harris Fetko the frontier between petulance and rage was generally left unguarded, and he crossed it now without slowing down.” And our realtor is described thus: “Bob Hogue was a leathery man of indefinite middle age, wearing a green polo shirt, tan chinos, and a madras blazer in the palette favored by the manufacturers of the cellophane grass that goes into Easter baskets.”

If you decide to take a look at these stories, you’ll enjoy this kind of vivid language, and you’ll be rewarded with the tour de force horror story in the end. It’s also fascinating to consider this book as the one that immediately preceded the publication of Chabon’s work of genius, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, in which he might be said to break out of the mold of the conventional realist novel. Prior to that novel, Chabon was most often compared to Fitzgerald, or occasionally Cheever or Updike. After Kavalier and Clay—well, he’s a genius in his own right That shift seems to occur in this particular book, in the chasm between the first eight stories and “In the Black Mill.” If you’re a Chabon fan, you’ll definitely find this book worthwhile. If you’re a Chabon completist, you’ll have to.

NOW AVAILABLE:

To the Great Deep, the sixth and final novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at http://encirclepub.com/product/to-the-great-deep/

You can also order from Amazon (a Kindle edition is available) at https://www.amazon.com/Jay-Ruud/e/B001JS9L1Q?ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_1&qid=1594229242&sr=8-1

Here’s what the book is about:

When Sir Agravain leads a dozen knights to arrest Lancelot in the queen’s chamber, he kills them all in his own defense-all except the villainous Mordred, who pushes the king to make war on the escaped Lancelot, and to burn the queen for treason. On the morning of the queen’s execution, Lancelot leads an army of his supporters to scatter King Arthur’s knights and rescue Guinevere from the flames, leaving several of Arthur’s knights dead in their wake, including Sir Gawain’s favorite brother Gareth. Gawain, chief of what is left of the Round Table knights, insists that the king besiege Lancelot and Guinevere at the castle of Joyous Gard, goading Lancelot to come and fight him in single combat.

However, Merlin, examining the bodies on the battlefield, realizes that Gareth and three other knights were killed not by Lancelot’s mounted army but by someone on the ground who attacked them from behind during the melee. Once again it is up to Merlin and Gildas to find the real killer of Sir Gareth before Arthur’s reign is brought down completely by the warring knights, and by the machinations of Mordred, who has been left behind to rule in the king’s stead.