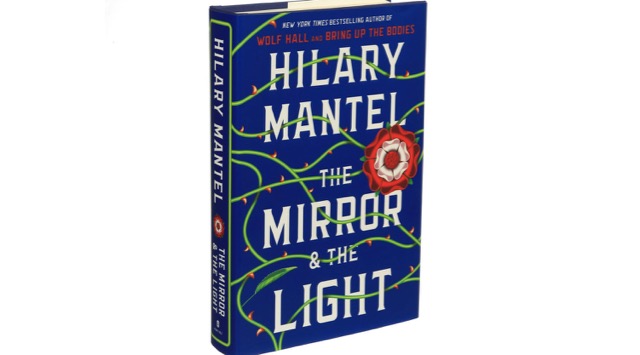

The Mirror & The Light

Hilary Mantel (2020)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

If you have read the first two books in Hilary Mantel’s epic historical trilogy covering the career of Renaissance English statesman Thomas Cromwell, you are no doubt poised to finish the story by reading the third and final novel, The Mirror & The Light. You should know from the outset that this is going to take some real commitment: This last volume is 754 pages in its American edition—if you happen to listen to it on Audible, it’s longer than 38 hours—only minutes short of the combined length of Wolf Hall and Bring Up the Bodies, the first two books. But if your experience of the text is anything like mine, you will regret that ending when it comes, and Cromwell is silenced forever. Mantel won the Booker Prize for Wolf Hall in 2009, and joined a very exclusive group (including only herself, Peter Carey, J.G. Farrell, Margaret Atwood, and Nobel laureate J.M. Coetzee) of writers that have won the award twice. The Mirror & The Light, which came out in March of this year, has now been long-listed for this year’s award, and appears to be the favorite, so the there is a good chance Mantel will become the first three-time winner of the coveted prize.

In Wolf Hall, Mantel recounted the rise of Thomas Cromwell in the service of Cardinal Wolsey, and his stepping into the Cardinal’s shoes as Henry VIII’s primary counselor after Wolsey’s fall from grace. It takes the story through Henry’s divorce from his first wife, Catherine of Aragon, his break from the Roman Church, and his marriage to Anne Boleyn. It ends with the death of Thomas More, who stubbornly refuses to accept Henry as head of the Church in England, though Cromwell bends over backward trying to save him. In Bring Up the Bodies, Henry’s relationship with Anne Boleyn deteriorates as she fails to give Henry a legitimate son and heir. Henry, now in love with Jane Seymour, wants to end his marriage with Anne, and charges Cromwell, now the king’s Master Secretary, with freeing him from this inconvenient wife. Cromwell tries at first to find legal means of ending the marriage. As he investigates Anne’s behavior she threatens his own position, and he finds that many of the people close to the queen are willing to pass on rumors of her infidelity to the king; ultimately Cromwell brings a case against Anne for adultery. One of Cromwell’s motivations is that a number of the men closest to Anne were instrumental in bringing down his old master, the Cardinal, and ultimately it is those men, including her own brother, George Boleyn, who are executed for adultery with the queen. Though Cromwell certainly suspects that not all the evidence against Anne is true, he is still willing to let Anne herself go to the executioner’s block, since it is what the king desires.

The Mirror and the Light begins immediately after Anne’s execution on 19 May 1536, and covers the last four years of Cromwell’s life, until his own execution on 28 July 1540. I apologize if that is a spoiler, but you had to know that a three-volume work dealing with a well-known historical figure is pretty certain to end in that figure’s demise. There is also, of course, a kind of symmetry achieved as Mantel ends each volume with an execution ordered by King Henry, and Cromwell’s death might be viewed by some as a sort of poetic justice: since he had been responsible for bringing about the execution of so many others, it is appropriate that he die in the same manner. Or, in the same vein, since Cromwell has devoted his life to serving a king whose whims, passions and egotism made him dangerous to anyone close to him, it was inevitable that his most effective instrument would ultimately end up as just another victim.

Still, the fact is that by the time we get to this third volume, we are heavily invested in Cromwell and his schemes.

The complexity of Cromwell’s character becomes more problematic as this long novel progresses. As Cromwell grows richer and more powerful, his motivations appear less and less pure. He has always been ready to do whatever the king requires, no matter how questionable its morality, but he has consistently tried to do the least harm. His vindictiveness began to appear in the denouement of Bring Up the Bodies, and here appears more openly at times (especially in an incident he relates from his youth that we have not been told of before), and his desire to enrich himself and his close supporters is more apparent here.

But at the same time, Cromwell’s virtues still shine through: He is still in this third book a “modern” man, a commoner who rose by his own skill and intelligence to threaten the entrenched interests of the aristocracy, a proponent of Protestantism against the interests of a smug and bloated Catholic tradition that serves the privileges of the old Plantagenet nobility, the Howards and the Poles, who think of England as their personal minibar. This is the Cromwell who believes that government can do something to help common people by improving roads and public works, but like many of his ideas that one is too progressive—“Parliament cannot see how it is the state’s job to create work,” he laments. This is also the Cromwell who has always done his best to stand between women and the king’s ire (well, except perhaps in the case of Anne), probably saving the lives of the king’s daughter Mary and his niece Margaret by teaching them to bend to Henry’s will.

But Cromwell must inevitably fall. In part his downfall is a result of his own merciful attitude toward his enemies: The old Catholic aristocracy of England, most significantly the Duke of Norfolk, Thomas Howard, were allied with him when he brought down Anne Boleyn, but are put out that he does not continue to do their will once Anne is gone. Cromwell had chances to bring Norfolk down but never does, because his military prowess is needed in the north to deter Scottish invasion, and unlike anyone else in the government, he puts the country’s interests ahead of his own. When Cromwell fails to have Reginald Pole, the traitorous scion of the Catholic Pole family who has called for Henry’s assassination, tracked down and murdered in Europe, Cromwell is in hot water with the king. And when, after Jane Seymour’s death in childbirth, Henry wants to marry again, Cromwell dismisses any alliance with either France or Spain, and argues that the king must be allied with the Protestant German princes. He arranges for Henry’s marriage to Anne of Cleves—a marriage that is a disaster from the moment the two see each other. This is a mistake from which Cromwell cannot recover.

But he is also brought down by his own hubris, helped along by those old Plantagenets. Cromwell, as Henry’s closest adviser, is the government, and begins to believe he is indispensable. At one point he thinks to himself “It is I who tell [Henry] who he can marry and unmarry and who he can marry next, and who and how to kill.” As the book’s title implies, he is the mirror to Henry’s light, a reflection of the king who performs the king’s wishes and takes the blame for the king’s decisions, but who knows Henry to be “a man of great endowments, lacking only in consistency, reason and sense.” At one point he recklessly says in what he believes to be a private conversation that if the king tries to move back into Catholicism, “Even if Henry does turn, I will not turn. I am not too old to take a sword in my hand.” It is a statement that will come back to bite him. So, too, does his kindness toward Henry’s daughter Mary. These two trivial things combine to allow his enemies to make a case that he is trying to marry Lady Mary and become king himself. And so, like the hero of a tragedy, Cromwell falls.

The final volume of Mantel’s trilogy recreates the Tudor era in spectacular detail and verisimilitude. With so much material to cover, it is probably less tightly focused than the previous books, but it is rich and rewarding. It would be perfectly justified for Mantel to sweep to her third Booker Prize for this book. In any case, it will definitely satisfy you if you are a fan of Mantel or a lover of history. Four Shakespeares.

NOW AVAILABLE:

To the Great Deep, the sixth and final novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at http://encirclepub.com/product/to-the-great-deep/

You can also order from Amazon (a Kindle edition is available) at https://www.amazon.com/Jay-Ruud/e/B001JS9L1Q?ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_1&qid=1594229242&sr=8-1

Here’s what the book is about:

When Sir Agravain leads a dozen knights to arrest Lancelot in the queen’s chamber, he kills them all in his own defense-all except the villainous Mordred, who pushes the king to make war on the escaped Lancelot, and to burn the queen for treason. On the morning of the queen’s execution, Lancelot leads an army of his supporters to scatter King Arthur’s knights and rescue Guinevere from the flames, leaving several of Arthur’s knights dead in their wake, including Sir Gawain’s favorite brother Gareth. Gawain, chief of what is left of the Round Table knights, insists that the king besiege Lancelot and Guinevere at the castle of Joyous Gard, goading Lancelot to come and fight him in single combat.

However, Merlin, examining the bodies on the battlefield, realizes that Gareth and three other knights were killed not by Lancelot’s mounted army but by someone on the ground who attacked them from behind during the melee. Once again it is up to Merlin and Gildas to find the real killer of Sir Gareth before Arthur’s reign is brought down completely by the warring knights, and by the machinations of Mordred, who has been left behind to rule in the king’s stead.