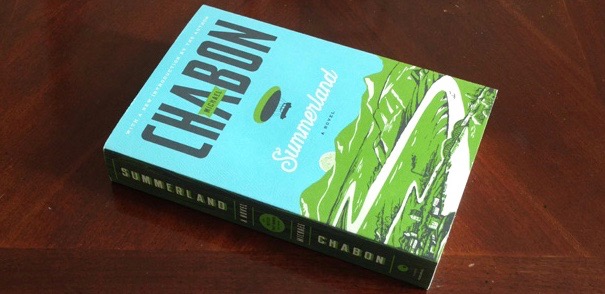

Summerland

Michael Chabon (2002)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Ruud Rating

4 Shakespeares

[/av_image]

I freely admit that it took me way too long to get around to reading Michael Chabon’s brilliant Pulitzer-Prize-winning Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clayand don’t mind declaring myself on the road to being a Chabon Completist (i.e., my goal is to read everything he’s written). But coming across Summerland was a bit unexpected. It’s Chabon’s first and only venture into YA fantasy, and so may come as something of a surprise. It was certainly a surprise to a number of readers and critics when it came out in 2002—for some an unpleasant surprise. For this is the Chabon novel that received the most mixed reviews on its publication. The New York Times, for example, described it as “bewilderingly busy,” while a British reviewer said that Chabon’s “story is chiefly informed by the type of whimsical drollery which, like a watched kettle, never quite manages to get to boiling point.” Chabon himself has written, in his 2009 book Manhood for Amateurs, that “anyone who has ever received a bad review knows how it outlasts, by decades, the memory of a favorable word,” and therefore it is just conceivable that, despite numerous positive reviews of Summerland, those other reviews have kept him from returning to YA fiction.

Which is too bad, because I found Summerland to be a delightful fantasy that ranks with some of the finest of post-Tolkienesque fiction. Certainly Chabon hasn’t given up on fantasy, since his swashbuckling Gentlemen of the Road and his entertaining Yiddish Policeman’s Union make liberal use of that genre. But coming when it did, Summerlands was subjected to inevitable comparisons with Harry Potter: Harry had a male and female companion, while Ethan Feld, hero of Summerland, had a male friend (Thor, a boy who thinks he is an android) and a female friend (Jennifer T., a girl who turns out to be a star pitcher); Harry had a wand that chose him, Ethan has a bat made especially for him from a piece of the World Tree; Harry battles the personification of evil in Voldemort, Ethan battles an archetypal nemesis in Coyote, who is trying to bring about the end of the world; Harry is obsessed by the national sport of wizardry, Quidditch; Ethan by America’s national pastime, baseball (that same British critic complained that the baseball terms in the novel are bewildering and that the completely imaginary Quidditch is more comprehensible, but can anybody take a comment like that seriously from somebody in a country that supports the thoroughly Byzantine sport of Cricket?).

But these similarities do not make the book derivative. At least no more than any other modern fantasy, Rowling’s included. Chabon includes a fairly lengthy introduction in the 2011 paperback reprint of the book in which he describes his own childhood fascination with the idea of fairies, or the concept of what Tolkien more accurately described as “Faerie,” that mythical realm of the supernatural and what Tolkien called “secondary creation”—the author’s god-like imaginative invention of another world. Thus Summerland has roots not only in Rowling but in Tolkien (a lengthy quest ending in a battle for the end of the world), C.S. Lewis (a plethora of mythical and animal helping figures), Philip Pullman and Madeleine L’Engle (the quest includes a rescue of an endangered father figure). Like Tolkien, he has also plumbed the depths of ancient mythologies that first formed our notion of Faerie, especially Native American traditions of the Coyote Trickster who is the chief antagonist of the novel, and Old Norse traditions that picture the universe as centered in a great tree (Yggdrasil), fed by a well (the well of Urd), which will fall and the end of time, at Ragnarok, when the gods will be defeated by the powers of darkness. In Summertime, the end of the world is called “Ragged Rock,” the time that Ethan and his friends must try to prevent, as the Norse gods strove to put off Ragnarok for as long as they could.

Of course, the other important aspect of the novel is baseball, a sport with which Chabon, as he describes in his introduction, has always been obsessed with himself. And why not? Baseball is the sport most congenial for writers, its archetypal romance qualities made manifest by such mythic narratives as The Natural and Field of Dreams, as well as by real-life heroes in the form of Jackie Robinson, Lou Gehrig, Satchell Paige, Sandy Koufax, Henry Aaron, Mike Trout, et al., or legendary events like Dimaggio’s hitting streak, Babe Ruth’s called shot, Bobby Thompson’s “shot heard round the world,” or the ending of the Chicago Cubs’ 108-year title drought. But I digress. Sure there was the Black Sox scandal, Pete Rose’s betting scandal, the darkness of the steroid scandals, and the recent sign-stealing bruhaha, but that’s life. And Chabon is very clear that baseball is in many ways a metaphor for life. In what other sport can you fail 70 per cent of the time and still be a hero? In what other sport does the best team lose almost as many games as it wins, or the worst team lose only a few more games than it wins over a 162-game season? Will you be so boorish as to imply that baseball is a slow-moving game? Chabon tells you here in no uncertain terms that “A baseball game is nothing but a great slow contraption for getting you to pay attention to the cadence of a summer day.”

Thus the epic journey of Chabon’s novel involves Ethan, Thor, Jennifer T., and their friends barnstorming through supernatural realms where they engage in baseball games with higher and higher stakes, until the ultimate game against Coyote’s team that will decide the fate of the universe. To put it into a scarcely comprehensible nutshell, 11-hear-old Ethan is the worst baseball player on the worst Little League team on Calm Island (off the coast of Washington). But he meets a werefox named Cutbelly, who tells him about the Lodgepole (i.e., the World Tree) that connects the four worlds, between which one can scamper if one knows how. He is also recruited by the ancient scout Chiron “Ringfinger” Brown, one-time pitching great (an allusion to Hall of Fame Cubs’ pitcher Mordecai “Three Finger” Brown) and now recruiter of heroes (an allusion to Chron, the Centaur of Greek mythology who trained such heroes as Achilles, Ajax, Perseus and Theseus). Brown recruits Ethan to come to Summerland, the land of the fairy folk called ferishers, to help shore up their baseball team and thereby to help defeat Coyote, who is determined to destroy the Lodgepole and bring about Ragged Rock. At the same time, Ethan must track down his father, an engineer whom Coyote has captured and is forcing to produce a batch of his invention, the virtually indestructible “picofiber.” Coyote intends to use this substance to create a container for the toxic poison with which he plans to foul Murmury Well, the water source for the World Tree. Ethan, Jennifer T., and Thor put together a “fellowship” of nine representatives of various races of Summerland (sound vaguely familiar?) to form a baseball team: These include a ferisher chief named Cinquefoil, a dwarf-sized giant, a depressed female Sasquatch, a talking rat, and a “ringer” in the form of an over-the-hill Cuban defector-ballplayer from their own world, who play their way across Summerland to the final Armageddon-like ballgame against Coyote.

I won’t give away anything with spoilers here about the outcome of the game, or the book. But the above synopsis is a pretty good indication of the complexity of the novel. So even though its alleged audience is the YA range of 10- to 15-year-olds, Chabon’s adult fans will want to read it if they haven’t already. It’s definitely not a children’s-level book in terms of its theology or world view. Coyote is a case in point: Most reviewers of the book refer to him as a demonic character, an embodiment of evil, like the Christian Satan. But Chabon is careful to name him Coyote—the Trickster figure of Native American cosmology. He also is clearly drawn from the Old Norse Loki, another Trickster who, like the Old Testament Satan of the book of Job, is part of the heavenly court. Coyote is not pure evil. As Prometheus, he brought fire to human beings. He separated the world of men from the word of gods, making human beings responsible for their own actions. And, in Chabon’s book, he also invented baseball. How can that be bad? Of course, he is also responsible for the invention of the Designated Hitter rule, which Chabon correctly attests has all but ruined the game.

The point is that Coyote, or Loki, or any mythological Trickster, is not evil incarnate but rather that figure who violates the principles of social or natural order, embodies that ungovernable and unpredictable element of the universe or of life present in every endeavor, that element which must be anticipated and dealt with in any true picture of life: it’s the error, the grounder that takes a bad hop, the bloop single, the Steve Bartman, that unpredictably changes the outcome of the game, of life, or of the universe.

Chabon’s book is a boisterous, rollicking, freewheeling, adventurous, epically wild turmoil of a novel that, if you like fantasy and baseball in equal measure, you will love. I loved this book.

NOW AVAILABLE:

“The Knight of the Cart,” fifth novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at https://encirclepub.com/product/theknightofthecart/

You can also order from Amazon at

https://www.amazon.com/Knight-Cart-MERLIN-MYS…/…/ref=sr_1_1…

OR an electronic version from Barnes and Noble at

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-knight-of-…/1133349679…

Here’s what the book is about:

The embittered Sir Meliagaunt is overlooked by King Arthur when a group of new knights, including Gildas of Cornwall, are appointed to the Round Table. In an ill-conceived attempt to catch Arthur’s notice, Meliagaunt kidnaps Queen Guinevere and much of her household from a spring picnic and carries them off to his fortified castle of Gorre, hoping to force one of Arthur’s greatest knights to fight him in order to rescue the queen. Sir Lancelot follows the kidnappers, and when his horse is shot from under him, he risks his reputation when he pursues them in a cart used for transporting prisoners. But after Meliagaunt accuses the queen of adultery and demands a trial by combat to prove his charge, Lancelot, too, disappears, and Merlin and the newly-knighted Sir Gildas are called into action to find Lancelot and bring him back to Camelot in time to save the queen from the stake. Now Gildas finds himself locked in a life-and-death battle to save Lancelot and the young girl Guinevere has chosen for his bride.