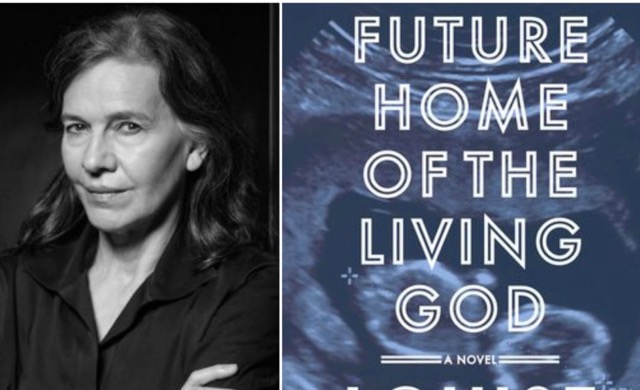

Future Home of the Living God

Louise Erdrich (2017)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Tennyson-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’77’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

There’s no doubt that Louse Erdrich is one of the pantheon of American writers whose novels are always greeted with anticipation and excitement, who has produced so many critically acclaimed works over several decades that the next book is always an event. From her debut novel Love Medicine in 1984 (winner of a National Book Critics Circle Award), through the more mature Plague of Doves (a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in 2009), to her more recent successes with The Round House (winner of the National Book Award for 2013) and LaRose (winner of another National Book Critics Circle Award in 2016), her brand of fiction, rooted as it has been in her own experiences as a Turtle Mountain Chippewa, has struck a chord with everyday readers and critics alike.

So it’s a bit jarring to see some of the critical responses to Erdrich’s most recent novel, Future Home of the Living God (2017). One of the kinder critics wrote that the novel is “not entirely satisfying,” while another, less kind, called it “an overreaching, frequently bizarre book that never really comes close to getting off the ground.” A third said that “The writing is oddly flat, and occasionally inexplicable,” ultimately concluding that the “novel might be a well-intentioned disaster.” One wonders, if this had been a novel by some little-known writer rather than a much-honored national treasure, whether reviews would have been less negative. Oh, who am I kidding: Given the state of publishing these days, if it hadn’t been by a well-known writer it wouldn’t have been reviewed at all. Personally, while I don’t think I’m going to be remembering this book as vividly or as fondly as I do Love Medicine or Plague of Doves, I found the book to be very readable, fast-paced and meaningful, not to mention timely. I’m certainly not going to knock it for not being The Handmaid’s Tale.

For that will be the inevitable comparison readers will make. Like Atwood’s classic novel, Erdrich’s Future Home is set in a dystopian future United States in which an existential crisis involving human beings’ reproductive ability has incited the usurpation of the government by a party of extreme right-wing religious bigots who establish a theocratic dictatorship bent on controlling women’s reproductive rights. Two significant differences in the two novels are that, in Atwood’s, the theocracy is cemented in place and resistance seems futile. In Erdrich’s, the takeover is in process even as the story unfolds. Another difference is that Erdrich makes much more of the environmental crisis: Though the story takes place in the near future, the characters in the Minnesota setting of the novel have already seen their last winter with snow, and a ninety-degree day is “an unusually cool day for August.” But there is no question that one of the books that most influenced Erdrich’s was Atwood’s. Elle magazine, in a brilliant coup, printed an interview with Erdrich conducted by Margaret Atwood herself soon after Future Home was published, in which Erdrich says that she “profoundly admire[s]” Atwood’s book:

“Your book has always resonated for me. Fundamentalist religions always include religious laws that control the female body—you got that perfectly right, and invented such a horrifyingly normal society based on literal readings of scripture. Of course, The Handmaid’s Tale draws enormous energy from biological shuttering, or refusal. No babies, no future. No human race. Men find ways to engulf women and to manipulate the female body. We keep thinking about it, because we are always close to the edge. Women’s rights are just a watery paint on the walls of history. We must not forget.”

Erdrich’s intent is stated fairly succinctly in that paragraph. And her tone is more zealous toward the disaster that must be fended off, than Atwood’s, which seems elegiac toward the past that must be mourned. Atwood’s 1985 novel was prompted in large part by the new rise of the religious right in America that had brought about the election of Ronald Reagan and a real threat to Roe v. Wade. Erdrich’s book was begun in about 2002, after the renewed threat to women’s rights ushered in with the Bush administration, as well as the suppression of voices of dissent in the wake of 9/11 and the new rise of U.S. militarism. But Erdrich abandoned the novel after a few years, turning to her other projects, including Plague of Doves, and seemed unlikely to return to it…until the current occupant of the White House began his full frontal assault on women’s rights and on the environment. The time seemed ripe for a return to the themes of Future Home, and the same national mood that welcomed the televised version of Atwood’s novel seemed poised to receive this book of Erdrich’s. So she dusted off the manuscript, cut some 200 pages of it, and rushed it into print.

That rushing seems to have created some of the problems critics have found with the book. There are certain characters whose motivations seem fuzzy, and certain questions that remain unanswered at the end of the novel. But for the most part, it’s an entertaining read. The first half of the novel is fairly typical Erdrich: The book’s narrator, Cedar Hawk Songmaker, is a member of the Ojibwe tribe, but is the “adopted child of Minneapolis liberals,” she says. Ironically, her white liberal adoptive parents are named Songmaker (the father’s name, of English ancestry). When Cedar makes an effort to find and reconnect with her Native American birth family, she finds that her birth name was actually the very un-Indian sounding name of Mary Potts, that her mother’s name is also Mary Potts, and that her grandmother, one of Erdrich’s wise old Native grandmothers, is also named Mary Potts (“Mary Potts Senior,” in contrast with her daughter, Cedar’s mother, whom Cedar dubs “Mary Potts Almost Senior”). And just in case that’s not enough, Cedar also finds she has a younger sister, named, well, Mary of course (or “Little Mary”). Any romantic ideas that Cedar may have had about her birth family, noble denizens of the plain and preservers of the natural world and environmentally respectful Native traditions, are shattered when she finds they are a bourgeois clan who run a gas station and convenience store: “My family had no special powers with healing spirits or sacred animals. We weren’t even poor. We owned a Superpumper.”

The scenes with the Native family are some of the most effective in the book. Cedar’s mother is a devout Catholic bent on getting the tribe to put up money for a park honoring indigenous saint Kateri Tekakwitha, in part to ramp up tourism in their northern Minnesota town. Little Mary is a teenager chiefly interested in developing her“Goth-Lolita” look and persona, and in not cleaning her room. Cedar’s step-father Eddy may be the most memorable: A Ph.D. who spends his time working at the gas station, he is writing a manuscript to which he daily adds a new page detailing one reason he did not kill himself that day. The manuscript is now more than 3,000 pages.

Where the book careens into new territory for Erdrich is when we discover why she is so interested in meeting her birth family now, at the age of 26: She is pregnant, and in fact the book itself is a long letter written to her unborn child. She wants to know whether there is any history in the family of birth defects or other genetic deformities. The reason she is so interested is that, apparently as a result of climate changes, evolution has stopped and apparently reversed itself, so that ladybugs are being born the size of cats, and birds are giving birth to half-reptilian Archaeopteryxes. More disturbing, human babies are being born as throwback Cro-Magnons or worse. As Cedar says, “Maybe God has decided that we are an idea not worth thinking anymore.”

It’s a fascinating twist never completely developed. The newly instated government wants to ensure that they keep every pregnant woman in their control, and babies seem to be kept from their mothers and either killed or held for study, while at the same time women of child-bearing years are being coerced into acting a surrogate mothers for embryos produced in pre-apocalypse years. For the sake of avoiding spoilers, I won’t say how all this affects Cedar, or her baby, or how the baby’s father helps or hinders Cedar’s quest to control her own pregnancy and birth. I will say that it becomes a fast-paced suspense novel in the end that makes you want to keep reading.

For me the reverse-evolution aspect of the book was hard to fathom, since it presupposes that evolution is a progress and not a random process steered by adaptation to environment. In other words, the “regression” to previous biological forms seems unlikely, as opposed to human adaptation to the climate-changed world as a new creature (as Kurt Vonnegut describes in his similar-themed novel Galapagos). But this does not undermine the theme of the novel, or the likelihood that drastic changes in the environment will affect human life as drastically as other forms of life.

Ultimately, although I do believe Erdrich has written better books and perhaps could have made this one better with a few careful changes, this is still a good read and a page turner. I’ll give it three Tennysons.

NOW AVAILABLE:

“The Knight of the Cart,” fifth novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at https://encirclepub.com/product/theknightofthecart/

You can also order from Amazon at

https://www.amazon.com/Knight-Cart-MERLIN-MYS…/…/ref=sr_1_1…

OR an electronic version from Barnes and Noble at

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-knight-of-…/1133349679…

Here’s what the book is about:

The embittered Sir Meliagaunt is overlooked by King Arthur when a group of new knights, including Gildas of Cornwall, are appointed to the Round Table. In an ill-conceived attempt to catch Arthur’s notice, Meliagaunt kidnaps Queen Guinevere and much of her household from a spring picnic and carries them off to his fortified castle of Gorre, hoping to force one of Arthur’s greatest knights to fight him in order to rescue the queen. Sir Lancelot follows the kidnappers, and when his horse is shot from under him, he risks his reputation when he pursues them in a cart used for transporting prisoners. But after Meliagaunt accuses the queen of adultery and demands a trial by combat to prove his charge, Lancelot, too, disappears, and Merlin and the newly-knighted Sir Gildas are called into action to find Lancelot and bring him back to Camelot in time to save the queen from the stake. Now Gildas finds himself locked in a life-and-death battle to save Lancelot and the young girl Guinevere has chosen for his bride.