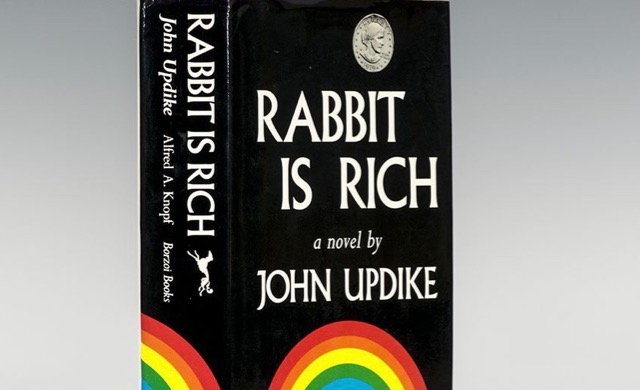

Rabbit Is Rich

John Updike (1981)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Tennyson-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’77’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Rabbit Run, John Updike’s classic 1960 novel introducing the antiheroic everyman Harry “Rabbit” Angstrom into American literature, was listed on Timemagazine’s famous 2010 list of the “100 greatest English-language novels published since 1923” (the year Timewas born) I’d never read the novel, and resolved last year to correct that oversight, and so read it and its sequel, Rabbit Redux, set, and published, ten years later. Now, having lost myself completely down the rabbit hole, I’ve completed the third novel in Updike’s tetralogy, Rabbit is Rich. This is a book that won Updike his first Pulitzer Prize in 1982, as well as the National Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction. That is a significant achievement, and one cannot help approaching the novel with some trepidation, wondering if it can possibly live up to its reputation.

You have to remember, coming to this book after meeting the Rabbit of 1960 and the Rabbit of 1970 (which you really need to do before tackling this book), that Harry Angstrom is just not that likeable a guy, and you’re not really likely to find the Rabbit of 1980 any more palatable. After all, the name “Angstrom” fits him pretty well: That mind of his quivers with angst like a rabbit’s nose. And here more than in the previous books it is hard to ignore the similarity of the name “Rabbit” to Sinclair Lewis’s “Babbit”—a character whose name has entered the English language to mean “a person and especially a business or professional man who conforms unthinkingly to prevailing middle-class standards.”

In Updike’s first two Rabbit books. Harry chafed—with much angst—against the conventions of the middle-class society to which he aspired, leaving his wife and son out of the blue and ultimately taking up with another woman, Ruth, living with her in defiance of popular opinion, before returning to Janice, his wife. In Rabbit Redux, Janice has left him ten years later to live with Charlie, a salesman at her father’s car dealership, and Harry takes in a wayward young girl and a prickly black revolutionary named Skeeter, who educates him in black history—a living arrangement much to the chagrin of his white neighbors, who ultimately burn down his house, killing the girl and driving Skeeter into hiding. But by this third book, Rabbit, now back and solidly married to Janice, is living in her parents’ house after the death of Janice’s father, and is now running her dad’s old Toyota dealership. It’s 1979, and the fuel crisis is driving gas prices through the roof and prompting people to buy small foreign cars with excellent gas mileage—so the Toyota dealership is cleaning up, and Rabbit is rich.

Now in his paunchy mid-forties, Rabbit has settled down in his fictional down at-the-heel hometown of Brewer, Pennsylvania, into a comfortable upper-middle-class Babbit-like existence: He and Janice, now married 22 years, belong to the country club and spend most of their free time there, mainly drinking with three other couples, investing in gold and silver in the face of economic uncertainty, finally buying a house to replace the one that burned down in the previous book and worrying about their son Nelson, who’s grown into a feckless kid who’s dropped out of college at Kent State after having impregnated a girl who really doesn’t seem all that into him. The fact that Rabbit’s new house and lifestyle would have embarrassed his own working-class parents seems to be fine with him, though the fact that Nelson is looking at a shotgun wedding disturbs him since it is too much like a replay of Rabbit’s own past trials. And then there’s Janice’s drinking: This seems to be a perpetual problem, and in fact caused the death of their infant daughter in the first novel when Janice drowned her in the bathtub. Interestingly, Rabbit is the one everyone blames for that. Harry’s libido is another perpetual problem, or character trait as I suppose he would call it. He mentally undresses pretty much every woman he sees and evaluates her as a potential sex partner, including his son’s girlfriend, and including (obsessively) the young trophy wife of one of his country club buddies.

The latter plot point reaches a climax, no pun intended, when Harry and Janice take a Caribbean vacation with two of their country club crowd, and the three couples decide to engage in a night of wife-swapping—something that had become a daring fad in the “Swinging ’70s”—but Harry ends up not with the woman after whom he’s been lusting for months, but with the other wife, Thelma, a woman he’s never been interested in at all but who, it turns out, has been lusting after him for years.

You have to face it that Harry is really not an admirable character, in fact is something of a boor. But there is something about him, buried beneath the surface—sometimes very deep beneath the surface—that is a core of goodness and basic humanity. He’s something of a casual bigot, yet in RabbitReduxhe became friendly with a number of black characters and listened to Skeeter’s radical speeches with interest. In this book he seems genuinely moved when he hears of Skeeter’s death. He’s not a misogynist but he’s certainly a male chauvinist who sees women mainly as pieces of meat, but he’s actually interested in them as people once he gets to know them. So while his night with Thelma is not exactly his finest hour, he actually talks intimately with her about herself and her illness. He even has a oft spot for his wife’s old lover Charlie, whom he fights to keep on at the car dealership when Janice and her mother want to fire him and hire Nelson. And while he walked out on his pregnant lover Ruth to go back to his wife in Rabbit Run, he has never forgotten her and, in this book, meets a young woman who comes into his dealership with her boyfriend who is the right age and is from the right place in the country and who looks something like Ruth—and himself—so that he becomes obsessed with finding out if she is in fact his daughter. (Of course, he does this only after he’s ogled her and thought about what sex would be like with her, as he does with every other woman). Partly it is disappointment with his son, and the old grief of having lost his legitimate daughter, but Harry seems to truly want to help this girl the only way he can think of—with money, that he thinks might help her get to college.

Ruth tells Harry that he is all “me, me and gimme, gimme.” Thelma, on the other hand, tells Harry that she thinks he is “radiant,” particularly in “the way you never sit down anywhere without making sure there’s a way out.” The truth is not, as you might suspect, somewhere in between. The truth is that both things are true. Rabbit Angstrom is both a greedy egotist and a person who can rise to surprising if not heroic empathy. All the while he is haunted by the deeper questions of existence—age and death and God—but he’s at a point when his material possessions can stop his ears to those kinds of things. And even with these he can be an egotist. Considering all those he has lost in his life, he opines. “Maybe the dead are gods, there’s certainly something kind about them, the way they give you room. What you lose as you age is witnesses, the ones who watched from early on and cared, like your own little grandstand.”

No, Harry’s not just reprehensible. It wouldn’t be worth reading, or writing, four books about him if he were. He’s an average American—maybe a little below average, like a C minus—who seems redeemable. We just have to see if he turns out redeemed. Overall, this is a good book—maybe not as great as its list of awards might indicate, but certainly worth reading.

NOW AVAILABLE:

“The Knight of the Cart,” fifth novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at https://encirclepub.com/product/theknightofthecart/

You can also order from Amazon at

https://www.amazon.com/Knight-Cart-MERLIN-MYS…/…/ref=sr_1_1…

OR an electronic version from Barnes and Noble at

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-knight-of-…/1133349679…

Here’s what the book is about:

The embittered Sir Meliagaunt is overlooked by King Arthur when a group of new knights, including Gildas of Cornwall, are appointed to the Round Table. In an ill-conceived attempt to catch Arthur’s notice, Meliagaunt kidnaps Queen Guinevere and much of her household from a spring picnic and carries them off to his fortified castle of Gorre, hoping to force one of Arthur’s greatest knights to fight him in order to rescue the queen. Sir Lancelot follows the kidnappers, and when his horse is shot from under him, he risks his reputation when he pursues them in a cart used for transporting prisoners. But after Meliagaunt accuses the queen of adultery and demands a trial by combat to prove his charge, Lancelot, too, disappears, and Merlin and the newly-knighted Sir Gildas are called into action to find Lancelot and bring him back to Camelot in time to save the queen from the stake. Now Gildas finds himself locked in a life-and-death battle to save Lancelot and the young girl Guinevere has chosen for his bride.