https://www.circologhislandi.net/en/conferenze/Tramadol 50Mg Buy Uk Nous Nous

Tramadol Where To Buy Uk John Vanderslie (2022)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

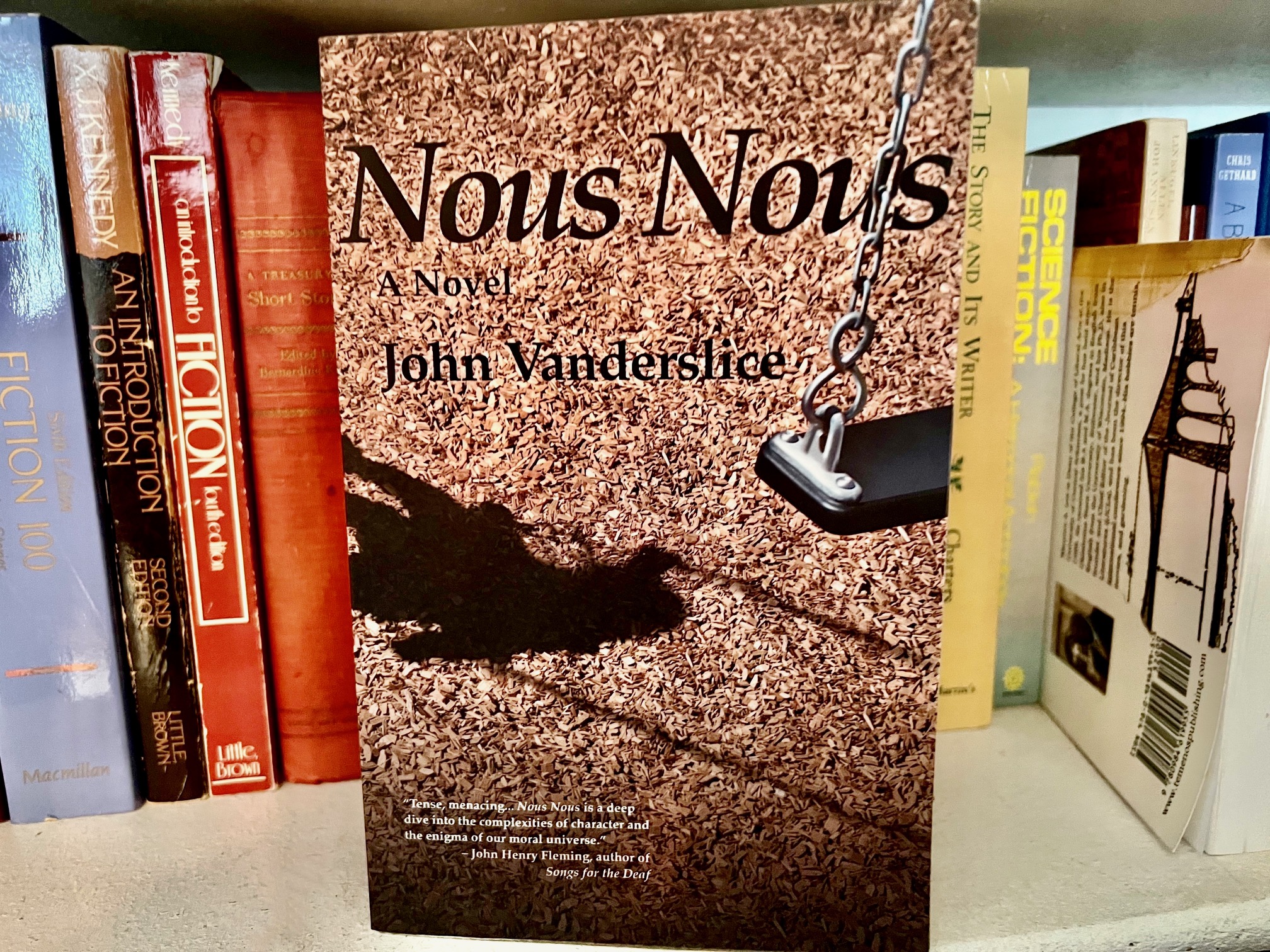

It’s been a long time since I read a book that I literally could not put down. But that is the case with John Vanderslice’s new novel Nous Nous.

Much of the reason for this urgency is the book’s affinities with the standard cinematic suspense thriller. It has the feel for much of its plot of a film like Taken—a daughter is kidnapped here, and much of the novel concerns her mother’s frantic efforts to find the girl and her captor before it’s too late, before the unthinkable happens and the girl is lost forever.

But if that were all there were to this novel, it would simply be a potboiler: easily consumed, digested and forgotten about. Something to pass the time until the next titillating distraction comes along. However, this novel transcends the thriller genre. For awhile, it seems as if it’s heading for an unusual and life-affirming denouement. But Vanderslice does not even play that expectation out to the end, and the final outcome is neither of the ones we have been expecting.

If you are one of that vast majority of Americans who has never studied any French to speak of, the book’s title must need some explaining. “Nous” is the French word for “we.” The title, then, is literally “we we”—not to be confused with “oui oui,” or “yes, yes.” (Just a little French joke there). Grammatically, in French, the second “nous” of the title is reflexive, which is to say, the title means “we ourselves.” Vanderslice himself has said in an interview that he decided on the title after writing a scene in which one of the characters, a French teacher, explains reflexive phrases to her class, and introduces nous nous. “I realized that the phrase captured the sense of collective longing that I seemed to be developing,” Vanderslice said. But the grammar suggests more: In French, nous nous is used with a verb, so that nous nous lavonsmeans “we wash ourselves.” Then what exactly might it mean in the title of this book? There is no verb. So exactly what is it we are doing to ourselves here? Perhaps that is the point. The title actually raises the question, “What are we doing to ourselves?”

The novel itself is a collective story. It is about “ourselves.” The narration alternates among four principal characters in the Arkansas town of Caddo (a thinly-disguised version of Conway, Vanderslice’s own home town): the French teacher—a college student named Angel who comes to the school once a week to try to get seventh graders interested in French; an Episcopal priest named Elizabeth Riddle, the mother of one of Angel’s students and embittered by a recent divorce; the daughter, Jeannine, a fairly typical middle school girl, more intelligent than most of her peers but mortified at the idea of standing out; and finally, a bereaved father named Lawrence Baine, whose own daughter was brutally murdered by a neighbor.

The action begins when Baine, clearly weighing the morality of what he is about to do, stops at the local Episcopal church and speaks to Elizabeth, the priest there. He suggests he is considering killing someone, but dances around his intentions and his doubts, and she is impatient with his evasions and put off by the red mark that dominates half Baine’s face. She peremptorily goes to fetch him a pamphlet called “Twenty Questions about the Episcopal Church.” Baine has disappeared before she returns.

Where he goes is the middle school where Elizabeth’s daughter attends. Baine has been casing the place at dismissal time for some days, walking by with his dog Cocteau (named, presumably, for the French director whose film Beauty and the Beast is reflected in the monstrous Baine’s kidnapping of Jeannine). The dog and the regularity of his walks seems normal and nonthreatening.

Baine has not chosen anyone in particular for his victim, but when Jeannine’s mother fails to arrive at dismissal time (she has had to deal with her son first), Baine approaches the girl and convinces her to leave with him, saying her mother was delayed and has sent him to pick her up. Only the intern Angel notices just who Jeannine leaves school with.

The rest of the novel unfolds as a simple thriller might, at least until the end. Yet because of the multiple perspectives, we become more and more familiar with Elizabeth and her personal trials, as well as Baine and the agonizing horrors that have made him what he is, and the almost unbearable terrors that Jeannine undergoes. Vanderslice succeeds in evoking at least a modicum of empathy for all of them.

More than a simple thriller, Nous Nous raises difficult questions about our lives in the world, and about our inner lives as well. Is “justice” a matter of retribution or restoration? If we purport to be a “Christian nation,” why is our society so violent? And why is violence our go-to response to difficult or threatening situations? How much is society responsible to individuals who have suffered soul-shattering trauma? If we ignore the most devastated in our midst, how much are we responsible for their condition? And can we then demand sympathy for our own shattering? If Christian love is the answer, can we truly love the worst monstrous of our fellows? And if we can do so in the abstract, can we do so when their monstrous behavior affects us directly in the real world? And finally, if we show the abstract face of love to those around us but fail to forgive those closest to us, what have we gained? In the spirit of nous nous, what have we done to ourselves?

I am simply overwhelmed but such a thoughtful and provocative review of my novel. Those are probably the wisest words I have ever heard about it. Thank you.