Tramadol Online Legal If you envisage heading for Europe any time soon in a wildly optimistic post-Covid (Ha!) gesture, you may be thinking of London or Paris or Florence. Maybe Oslo, Lisbon, Amsterdam. Vilnius may not pop up in your daydreams. But let me encourage you to think outside the well-worn box. Lithuania is an EU country (using the Euro) in the NATO alliance, and Vilnius, its capital, boasts an Old Town area recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site, as well as, a short ride away, a magnificent late Gothic red-brick castle at Trakai, built by the 14th century Grand Duke Vytautas in the middle of a lake.

Buy Cheap Tramadol Mastercard And if that doesn’t sell you on it, wouldn’t you like to visit a city in Russia’s neighborhood that has the chutzpah to put a huge Ukrainian flag on one of their tallest downtown buildings along with a giant sign basically telling Vladimir Putin where to stick it?

If you’re still thinking, “What does Lithuania have to do with me?” you might consider some of the well-known Americans who’ve been Lithuanian immigrants or were of Lithuanian descent. Starting with Al Jolson, star of Broadway and, later, several musical films, including the first “talkie,” The Jazz Singer. In the 1910s and 20s and into the 30s, Jolson was the world’s most famous entertainer. He was born in Lithuania. So was actor Lawrence Harvey (The Manchurian Candidate), while several other film names—Charles Bronson (The Great Escape), Sean Penn (Dead Man Walking) on his mother’s side, director Robert Zemeckis (Back to the Future) on his father’s side—are also Lithuanian Americans. What about Johnny Unitas, the original iconic franchise quarterback of the Baltimore Colts? Also of Lithuanian heritage.

A name you might not recognize is Frank Lubin, the son of Lithuanian immigrants who was a basketball star at UCLA and went on the help the U.S. National Team to a gold medal in the 1936 Berlin Olympics. He was invited to Lithuania to coach the fledgling Lithuanian team in the newly formed EuroBasket tournament. Lubin led the team to two consecutive gold medals (1937 and 1939) in what was essentially the World Cup of European hoops, and helped make basketball Lithuania’s national sport.

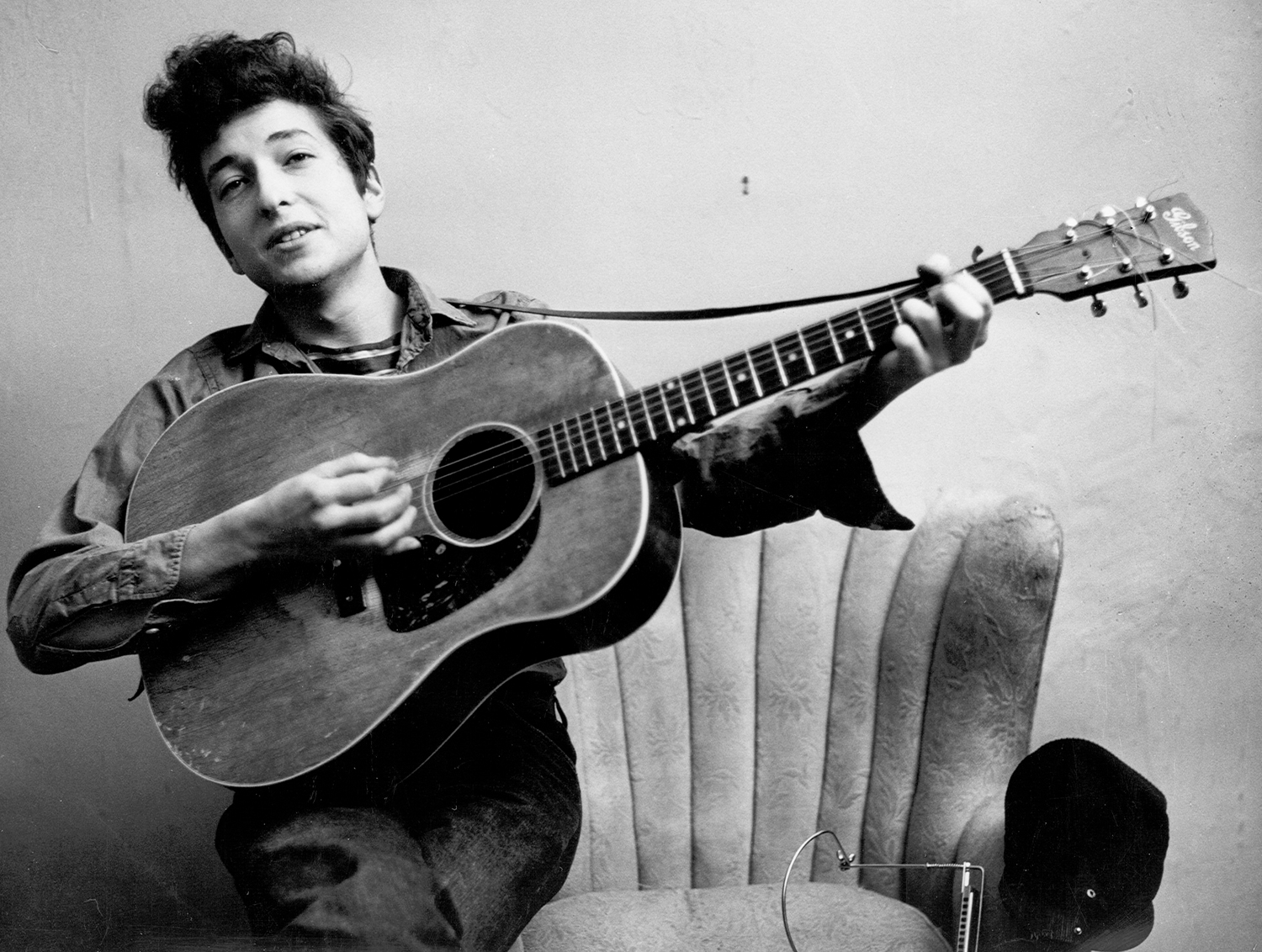

Another Lithuanian/American you might recognize was born in Duluth, MN 1941 to a mother whose parents were immigrant Lithuanian Jews (and to a father whose parents were immigrant Ukrainian Jews). They named him Shabtai Zisl ben Avraham, in English Robert Allen Zimmerman. You might know him better by his stage name, Bob Dylan.

I mention the Nobel Laureate here because, as you might recall, this is a post about writing and writers. And the fact is, Lithuanians seem to love their writers—enough that they actually commemorate them publicly in lavish civic displays. On our first night in town, walking the short distance from our hotel to Old Town to see the cathedral and its ancient tower, we passed a large square with a bronze statue of a man in the midst of it. The square was named for the man—“V. Kudirka.” So who’s he when he’s at home, I wondered. Some politician or war hero, I supposed. Turns out Vincas Kudirka (1858-1899) was a celebrated Lithuanian poet, who wrote the words and music to the Lithuanian National anthem Tautiška giesmė (literally “National Hymn”). Kudirka was expelled from the University of Warsaw as a radical because he had a copy of Das Kapital; then, being readmitted, he founded a secret society—Lietuva (“Lithuania”) devoted to Lithuanian nationalism, agitating for independence from the Russian empire. In 1889 the society began an underground newspaper called Varpas (“The Bell”) which Kudirka edited and published in for the next ten years. The text of Tautiška giesmė was published in Varpas in 1898, and when Lithuania became an independent country again in 1918, the poem became the official National Anthem.

Kudirka, who died of tuberculosis in 1899, did not live to see his dream of an independent Lithuania finally come true. But his words remain. In English, the poem says

Lithuania, our homeland,

Land of worshiped heroes!

Let your sons draw their strength

From our past experience.

Let your children always follow

Only roads of virtue,

May your own, mankind’s well-being

Be the goals they work for.

May the sun above our land

Banish darkening clouds around

Light and truth all along

Guide our steps forever.

May the love of Lithuania

Brightly burn in our hearts.

For the sake of this land

Let unity blossom.

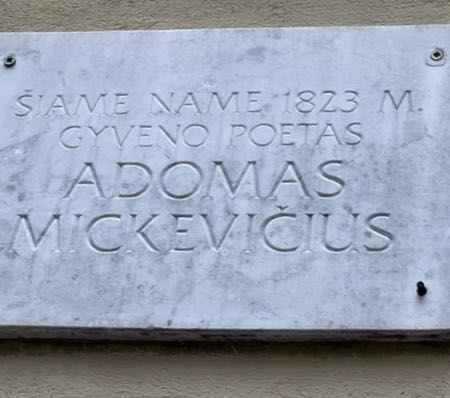

In Old Town itself, right next to the gorgeous late Gothic red brick Church of St. Anne, stands another larger-than-life statue of another poet and dramatist, one who was certainly one of Kudirka’s great inspirations: the Romantic era author who cut a swath across Europe in the vein of a Byron or even a Goethe—Adam Bernard Mickiewicz (1798-1855), who is regarded as Lithuania’s national poet. He’s also regarded as the national poet of Poland. Also of Belarus. How can this be, I can hear you thinking. Well, here’s the thing: he was born in what is now Belarus. He lived and attended university for four years in Vilnius, now the capital of Lithuania. And his family’s ethnicity was Polish, and he wrote in the Polish language. But this was not unusual at the time. You should know that the Commonwealth of Poland/Lithuania, which existed for 400 years and was the largest country in Europe, comprised not only modern day Poland and Lithuania but the other Baltic states too, as well as parts of Prussia, Russia, pretty much all of modern Belarus and Ukraine, all the way to the Black Sea. In the late 18th century, the three most powerful nations of the area—the Prussian Empire, the Hapsburg (Austrian) Empire, and the expanding Russian Empire—partitioned the commonwealth out of existence. Mickiewicz, growing up in the Russian part of the partitioned territories, wanted his country back. His whole country, and that included Poland, Lithuania, and Belarus.

His best known works are his drama Dziady (“Forefathers’ Eve”) and the epic poem Pan Tadekusz (subtitled “Last Forray into Lithuania”). These and his other works were instrumental in inciting uprisings in the partitioned lands. Mickiewicz was exiled to central Russia in 1824, but managed to leave the Russian empire in 1829 and spent the rest of his life, like Childe Harold, dragging his bleeding heart across Europe. He died, again recalling Byron, in Istanbul trying to organize Polish expatriates to fight against Russia in the Crimean War.

Not far from the statue, Mickiewicz’s house from his university days can also be seen. Here are the opening words of his epic Pan Tadekusz in the contemporary translation of Leonard Kress:

O Lithuania, my native land,

you are like health–so valued when lost

beyond recovery; let these words now stand

restoring you, redeeming exile’s cost.

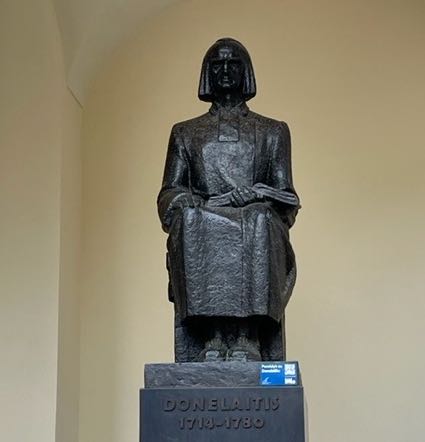

Also in the Old Town neighborhood of the University, one finds a tribute to another important Lithuanian author, Krisitjonas Donelaitis, known in Latin as Christian Donalitius (1714-1780). A Lutheran pastor of Prussian ethnicity, Donelaititis lived in a Lithuanian speaking area of Prussia and wrote the very first known poem in the Lithuanian language, a work called Metai (“The Seasons”) which is now considered classic in Lithuanian literature, describing the life of Lithuanian peasants living on the land and dealing with the annual cycle of life.

In 2009, Vilnius was designated by the EU as “European Capital of Culture,” a distinction given to cities for a year-long period during which the city organizes a variety of cultural events of a pan-European nature. One of the things Vilnius did can still be enjoyed on a long wall near Adam Minkiewicz’s house in Old Town: Artists from all over Europe created small tributes to favorite writers, and these vary across many centuries and many countries and languages, but my personal favorite was an artist’s tribute to Frank Zappa for his songwriting. If Dylan sprang from this country’s roots, it’s not surprising that they admire Zappa. There is, in fact, a bronze bust of Zappa somewhere in the city (we weren’t there long enough to track it down) erected shortly after the offbeat rocker’s death in 1993—the first such memorial in the world. Many Lithuanians saw him as a symbol of the freedom of expression they were enjoying in those years immediately following their independence from the Soviet Union.

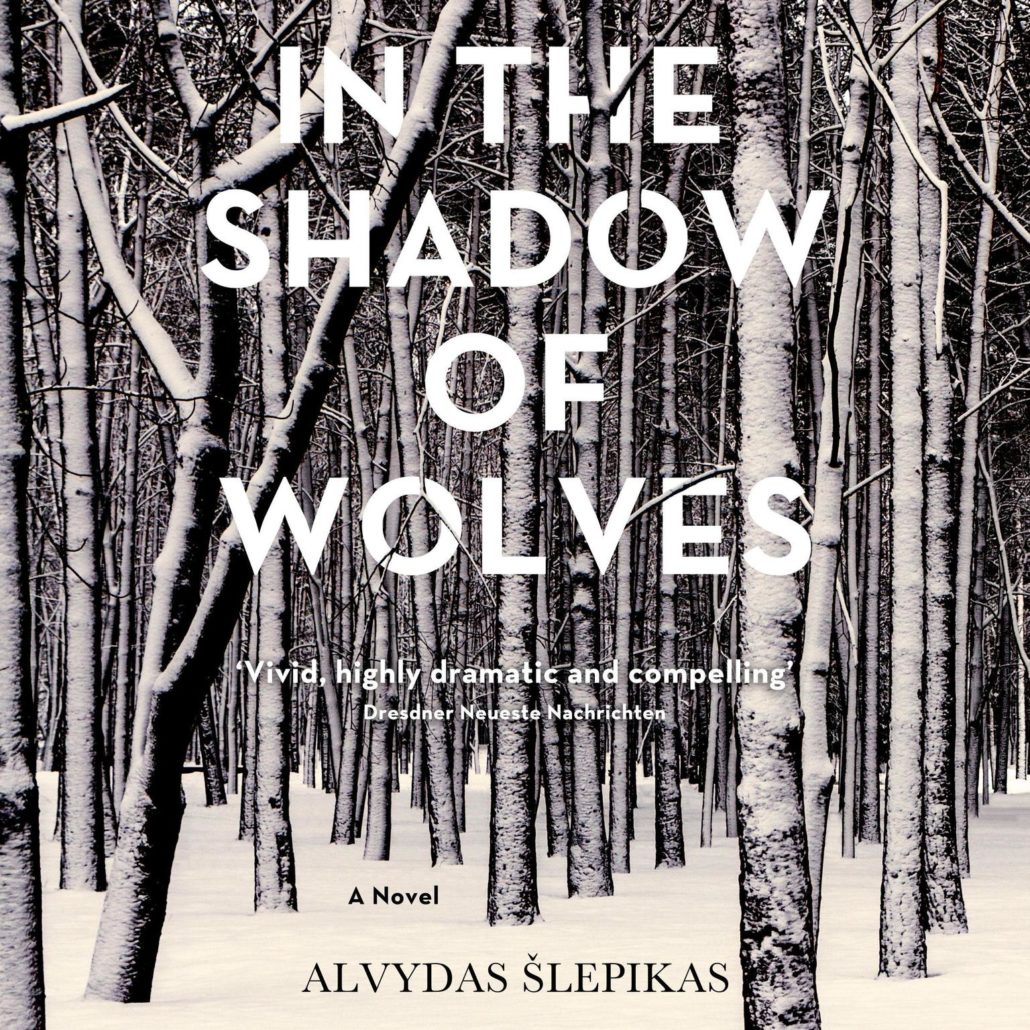

Let me leave you with a recommendation. If you’d like to read something by a contemporary Lithuanian writer, Alvydas Šlepikas (playwright, screenwriter, director, actor, and now novelist) might be of particular interest. His novel In the Shadow of Wolves, translated into English by Romas Kinka, was a New York Times best-seller and a Times book of the year in 2019. It’s a grim read—it opens with a Russian soldier throwing a grenade into a group of German children, and essentially moves off from there. But it’s the gripping, unflinchingly real story of life in the former East Prussia (now known as Kaliningrad) after it is occupied and annexed by Soviet troops at the end of the Second World War,

The novel’s Amazon blurb describes the book thus: “As victorious Russian troops sweep across East Prussia, a group of desperate children face a new battle. Confronted by critical food shortages and the onset of a bitterly cold winter, these ‘wolf children’ secretly cross the border into Lithuania in search of work or food to take back to their starving families. In a world still reeling from the devastation of war, the children must risk everything to survive.”

SPOILER ALERT: Some of them do not survive. But the book is an excellent read, hard to put down. And may be a good gateway into Lithuanian literature.