A.S. Byatt’s Possession: A Romance won the 1990 Booker Prize for Fiction. It appeared on Time Magazine’s list of the 100 greatest novels since 1923, and came in at #49 on the BBC’s list of the 100 Greatest British Novels. And for me, Byatt’s novel comes in at #15 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

This is a novel I let slip through the cracks when it first came out, but I made up for the gaffe last year, when my wife and I read it aloud over a period of a few weeks. It’s probably time I admitted something that everyone following my list and reading these little reviews has been aware of from the beginning: Much as I try to limit the influence subjectivity plays on my choices by focusing generally on novels that other important readers and critics have blessed before me, there’s no denying that my list is going to be different from those of others because I’m reacting to these novels from my own perspective—that of a white straight American male who grew up in the 1960s and still thinks that the Beatles are the pinnacle of popular music and Sandy Koufax is the greatest pitcher of all time. And who spent 40 years teaching college literature classes in Wisconsin, South Dakota, and Arkansas. So some books are naturally going to affect me more than they might someone with a different background, though I like to think that there are such things as universal themes—a belief that more recent Ph.D.’s might deny. But let me admit at the outset that Possession appeals to me in large part because its plot revolves around an academic literary project.

The novel focuses on Roland Michell, an English graduate student working in the London Library, and Dr. Maud Bailey, an English professor at a provincial university who has a reputation as an expert on the Victorian poet Christabel LaMotte. In the course of his research on another famous Victorian poet, Randolph Henry Ash, Roland discovers a hitherto unknown love letter written by Ash to a mystery woman not his wife. He suspects the woman may be LaMotte, and tracks down Maud to enlist her aid in solving the literary mystery. As the novel progresses, the reader follows the love affair between Ash and LaMotte through letters, journals, poems and other devices, and along with Maud and Roland watch the progress of the clandestine love affair between the Victorian poets, at the same time following the blooming affair between Roland and Maud. A number of surprising, even shocking revelations are uncovered by their exploration (none of which I’ll reveal to avoid spoilers), culminating in a meeting at Ash’s grave, where the scholars intend to solve the entire mystery by unearthing documents that Ash’s wife buried with him. The novel engages us on the level of a mystery or thriller, and also as a parallel love story set in both the present and the Victorian past. Byatt also plays with the modern genre of the comic “academic novel,” popularized by Kingsley Amis and David Lodge.

But transcending all these popular genres, Byatt also manages to explore universal themes of the nature of love and art, at the same time employing the devices of metafiction so dear to the post-modern novelist. The style of the mystery novelist, the style of modern academic prose, the style of Victorian prose and poetry, all combine in the novel to make it a kind of showcase of various literary techniques or ways to tell a story. The whole academic endeavor also raises questions in the readers’ minds about the authority of literary texts and their authors, including the apparently objective authority of the novel itself.

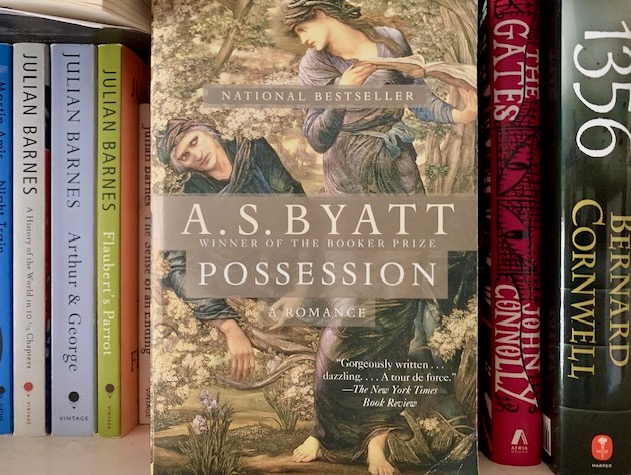

It’s fun to follow the way that Byatt plays with the details of the story. Ash and LaMotte are fictional poets, of course, but it seems that LaMotte’s biography is based on that of Christina Rosetti, while most people think Ash is based on Robert Browning—although the stature Ash reflects in this novel is more in line with Alfred, Lord Tennyson, and Ash’s share of 1700 lines of poetry Byatt composed for the novel seem more in the vein of Tennyson. The cover of the novel is a painting based on Tennyson’s Idylls of the King by the artist Edward Burne-Jones, a member of Christina Rosetti’s Pre-Raphaelite school. Byatt also teases us with the names of her main characters, Maud being the title of one of Tennyson’s more famous poems, and Roland recalling Browning’s “Childe Roland to the Dark Tower Came.” There are a number of other allusions made by the names in the novel, which is just one of the games Byatt plays with her readers.

The title of the novel, too, is a multivalent term. In the plot of the academic mystery, it seems to refer to the question, debated in the novel, of who has ownership of the literary papers and letters that Roland and Maud uncover. It also alludes to question of who owns the right to tell the story of Ash and LaMotte, as Roland and Maud find they have rivals in chasing down the story of the Victorian poets. The question of possession also arises in the competing claims of LaMotte and Ash’s wife to the love of the man—and of Ash and LaMotte’s long-time companion for her love. “Possession” may even suggest the manner in which love, like a demon, may possess one and drive one’s actions and decisions beyond one’s self control.

More than one reviewer at the time called the effect of Possession “dazzling,” particularly in the completely believable plethora of Victorian letters, journals, and poems all composed by a late 20th-century writer. If you like novels about academia, or mysteries, or love stories, or historical fiction, or metahistorical fiction, you’ll love this book if you’ve not already read it.