The titanic figure of William Faulkner looms above American modernism like his contemporary Babe Ruth towered over the ballplayers of his era. There is no question that Faulkner must appear on any list of the best books in English, even though, truth be told, it wasn’t until his Nobel Prize in 1949 that he began to command a large and faithful readership. Before that, he was seen largely as a regional Southern writer whose books tended toward violence and whose style was often too experimental for a wide readership—as if he were a James Joyce or something.

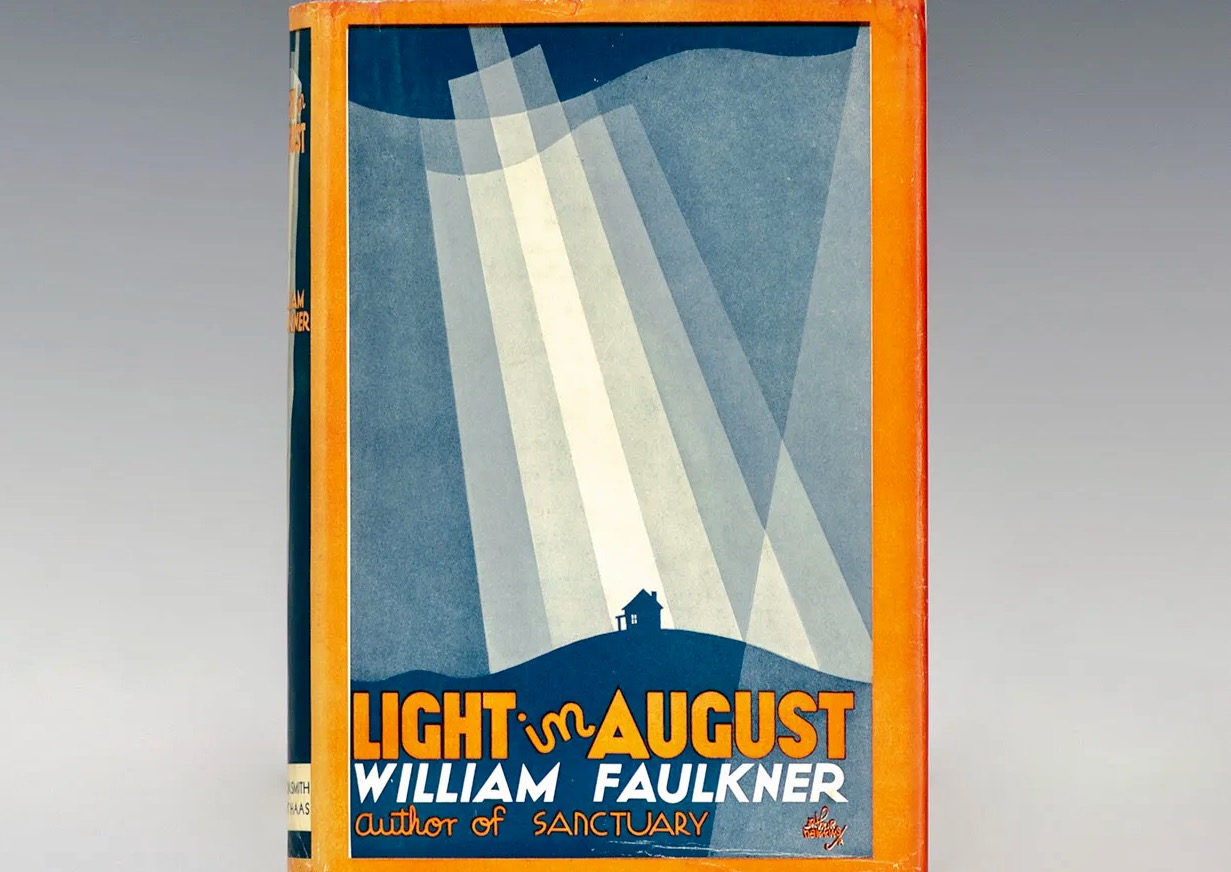

https://www.circologhislandi.net/en/conferenze/Purchase tramadol without prescription The question was not whether to include Faulkner. The question was which of Faulkner’s many masterpieces ought to be on my list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.” A popular choice would no doubt have been The Sound and the Fury, his 1929 novel in which he first used the stream of consciousness technique he had learned from reading Joyce. The Sound and the Fury is included as #6 on the Modern Library’s list of the 100 greatest novels of the twentieth century, and appears on Time magazine’s list of the top 100 novels written after 1923, and on the Norwegian Book Club/Nobel Institute’s list of the “100 Greatest World Novels of All Time.” Not a bad pedigree. That Modern Library list also includes Faulkner’s subsequent novel about the Compson family, Absalom, Absalom! (1936), the culmination of Faulkner’s stylistic experimentation. Perhaps even more acclaimed than these two novels is a third novel that utilizes stream of consciousness in a range of narrators (15 in all), As I Lay Dying (1930), which appears as #35 on the Modern Library list, and is included in the Guardian list of the best 100 novels in English, as well as the Observer’s list of the “100 Greatest Novels of All Time.” But I’m ignoring all of that and choosing Faulkner’s 1932 novel Light in August, a less experimental novel but one dealing with complex issues of race and gender, class and religion that still resonate in America nearly a hundred years after its publication. Light in August also appears on the Modern Library list, as #54, and on Time magazine’s list. I’m including it as book #31, alphabetically, on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

I first read Light in August when I was in my junior year of college. I read it in an upper level “Contemporary Literature” course (yes, Faulkner was actually still considered “contemporary” when I was in college). And I remember the professor saying that “If you’re going to like Faulkner, you’re most likely going to like him in Light in August.” At the same time, I was taking a course in “Tragedy” in which we were reading another of Faulkner’s most acclaimed novels, Absalom, Absalom!, as a specimen of tragic novel. As I was reading the two Faulkner novels simultaneously, what the former professor had said was brought home to me: The straightforward style of Light in in August made the book more immediately accessible, and hence more directly appealing, than the more impenetrable Absalom. It’s a book I’ve admired ever since.

The most emotionally engaging issue the novel explores is the obsession with race that persisted in the rural south in 1932, three quarters of a century after the Civil War. American obsession with race has hardly disappeared even now, well over another three quarters of a century since Faulkner’s novel. The book’s protagonist, the anti-hero Joe Christmas, happens to have a slightly darker complexion then the typical white southerner and, being raised as an orphan in Mississippi, cannot evade the suspicion that he may have a sprinkling of African American “blood” in his heritage. Thus like Mark Twain’s Puddnhead Wilson, he never quite knows whether he belongs to the white race or the black, and in the south at this time there is no middle ground. His life has been confusing and difficult, and sometimes violent, because of this suspicion, and while Christmas may be accepted as a white man wherever he goes, if once the suspicion of his “blackness” comes out, he is immediately recategorized by white society as a specimen in the “N word” category with all the prejudices and stereotypes that categorization would imply in the unenlightened south of 1932.

A secondary protagonist, whose story follows a parallel arc to that of Christmas in the novel, is the poor unmarried young pregnant woman named Lena Grove. The innocent and trusting Lena arrives as an outsider (like Christmas himself) in Jefferson, Mississippi (seat of Faulkner’s fictional Yoknapatawpha County). She has walked and hitchhiked all the way there from Doane’s Mill, Alabama, searching for the baby’s father, Lucas Burch, who she has heard may be working in a plaining mill there. Unlike virtually everyone she meets, Lena believes that Lucas will be glad to see her and will take care of her when she finds him. A local mill worker, the mild-mannered and upright Byron Bunch, dedicates himself to helping the passive and trusting Lena and to reuniting her with Burch, though he is in love with Lena himself. In fact, Lucas is in Jefferson—he has changed his name to Joe Brown and has partnered with Joe Christmas in a bootlegging operation.

Christmas, Lena and Byron are all outsiders in the evangelical Christian Jefferson of the novel, as is Byron’s friend the disgraced clergyman Hightower, as well as the woman Joanna Burden, the descendant of a family of Northern abolitionists who had moved to the county as carpetbaggers during Reconstruction. Christmas lives with Brown in a shack on Joanna’s land, and carries on a secret affair with her at night. But she ruins the relationship when she insists that Christmas pray with her. In one of many flashbacks of the novel, it becomes clear that at a young age Christmas was adopted by a grim tyrannical religious fanatic named McEachern, who tried to beat Christianity into his adopted son. At the age of 18, Christmas finally returned the beating and left McEachern for dead, becoming a wanderer. When Joanna turns up murdered and her house burnt down, the police first focus on Brown, who is found in the burning house. But when Brown suggests that Christmas may have “black blood,” the police drop all their suspicion of Brown and focus on the “Negro,” who must after all be guilty, because killing and raping white women is what black men do.

It’s frustrating to experience, even vicariously through reading, the blind and vicious racism that characterizes the citizens of Jefferson in Faulkner’s novel of the Jim Crow south. It is also frustrating that the truth of the two major assumptions that determine Joe Christmas’s life and death—that he was born with “Negro blood” and that he murdered his lover Joanna Burden—Faulkner never asserts. The two remain mere assumptions, and it is those insubstantial ideas that determine the actions of the people around him. Facts, evidence, truth, are all sacrificed on the shrine of blind prejudice.

One fascinating aspect of the novel’s reception is that it was translated into German and became quite popular with the Nazis of the 1930s, who missed the irony of the book altogether and read it as a manifesto on racial purity—a fact that ought to resonate with contemporary readers. It is significant that it is the misfits of this society—the Byrons of the novel—whose charity rises above the mass’s iniquity. Much has been made of the parallels between Joe Christmas and Christ, and at the same time between the husbandless and pregnant Lena and the Virgin Mary. Obviously Lena and Christmas fall far short of the ideals they recall, but it seems to me they represent those to whom Jesus in Matthew 25.40 refers when he says “Truly I tell you, just as you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me” (NRSV). It is thus Byron and Hightower, who attempt to help Lena and Christmas, whom Jesus would call “you who are blessed of my Father” (Mt. 25.34). That may be the biggest takeaway of the book.