https://www.circologhislandi.net/en/conferenze/ When I was in graduate school, some time back in the Jurassic period, I was assigned Henry James’ The Ambassadors to read for a seminar in literary theory. I remember slashing my way through the morass of James’ language like Henry Morton Stanley macheting his way through the thickest jungles in his search for Dr. Livingstone, he presumed. I was exhausted by the end of a day of reading maybe thirty pages in that dense text. Sometimes it would take me thirty minutes to read a page, often because I’d fall asleep twice before the end of the page, and I remember the extreme irony when I reached the point in the novel when the protagonist, Strether, advises a young man “Live! Live all you can! It’s a mistake not to!” And thinking to myself, this reading experience is the opposite of living all I can.

Tramadol Online Best Price My experiences reading some of James’s other major novels—The Golden Bowl, for example, and Wings of the Dove—were not quite as unpleasant, and I admit that Portrait of a Lady is not at all execrable. Still, when I began to assemble my list of the “100 Most Lovable Novel in the English Language,” I had little expectation that James would be included, despite his reputation as one of the great stylists in the language. As my very first review in this series stated (that was in Achebe’s Things Fall Apart) that no matter how high a novel’s reputation was among scholars and critics, I would not include in my list any books that, for me, were more of chore than a joy to read. So there seemed little chance for James.

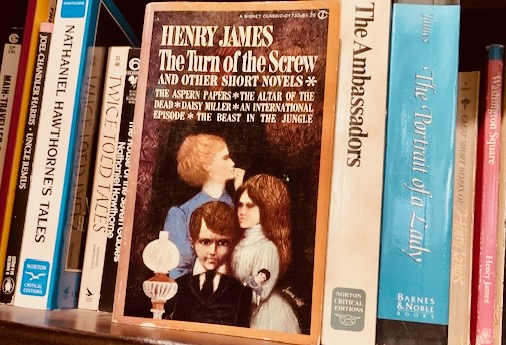

But then, to give James his due, I reflected that his short novels—the Washington Squares and the Beast in the Jungles and the Aspern Papers(es)—were surprisingly readable and enjoyable, and I realized that one of these in particular—The Turn of the Screw—was a psychological thriller unequaled by anything before and seldom equaled since. Hence, despite my initial misgivings, The Turn of the Screw becomes book number 50—the very center point of my list—of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

The excellence of Turn of the Screw has been often recognized. It’s on Penguin Random House’s list of “The Best Horror Novels of All Time.” You will also find it on a list of “61 Scariest Horror Novels Ever” on the website “Books & Bao.” Finally, there is an interesting web site called “The Greatest Books of all Time,” in which the site’s founder looked at 291 (that’s right, folks, you didn’t misread it) lists that purported to enumerate the best books in the world in any language. Using an algorithm (that I have no way of comprehending) that the researcher developed, s/he made a list several hundred titles long. These included nonfiction and non-English language books, but if one chooses only novels in English, there are three Henry James books on the list: Portrait of a Lady at number 41, The Ambassadors at 126, and Turn of the Screw at 164.

James’ employs the frame story convention in relating his ghost story. It’s Christmas Eve, and a group of friends are telling stories around a fire. The unnamed narrator tells how one of the others, a man named Douglas, reads a document written by his sister’s now late governess in which she reports, confesses one might say, how in a previous job she was hired by a man who had a young niece and nephew whose parents had died, and that he wanted a governess for (not caring to spend much of his own time with the children). The man lived in London but the children were living in his country house in Bly. As James sets up the narrative, he is telling a story about an unnamed man who is telling the story of a man named Douglas who is reading the story told by a woman he’s never met and who’s dead. As readers, we have a long way to go to get to the truth of this tale.

The ten-year-old nephew, Miles, is at boarding school, while the eight-year-old girl, Flora, lives at Bly with the housekeeper, Mrs. Grose. The uncle has given full charge of the children over to their new governess, whom he has instructed not to bother him about the children. Thus the governess has no one to discuss the children with or help her consider the things that begin to happen around her, other than Mrs. Grose, whose love for the children and belief that they are “angels” is hardly an impartial point of view.

The first disturbing occurrence is that a letter comes from Miles’ school, informing them that Miles has been expelled but not including the reason for the expulsion. And when Miles arrives back at Bly shortly after, he won’t talk about the expulsion, which leaves the governess to imagine possible terrible things that Miles may have done. Shortly after, the governess begins to see, around the grounds of the estate—figures that Mrs. Grose apparently cannot see, and that the children will not admit to seeing. But the governess does learn from the housekeeper that the children’s previous governess, Miss Jessel, had engaged in an illicit affair with the uncle’s valet, Peter Quint, and that when the scandal broke the two were discharged. They had both since died, but their close relationship with the two children leads the governess to believe that their malevolent spirits are now consorting with the children and influencing their actions.

After an incident in which Flora leaves the house and cannot be found until the governess and Mrs. Grose finally discover her on the shore of a small lake, where the governess also sees the spirit of Miss Jessel. She is convinced that lora has been talking with the ghost of her former governess, but Mrs. Grose says she see no one else there, and Flora will not admit that she does either. After this, Flora refuses to see her current governess again.

Ultimately, the governess decides that Mrs. Grose should take Flora to her uncle to get her away from Miss Jessel, and plans to stay with Niles and break Quint’s influence on the boy. This does lead to a chilling and ambiguous ending which, of course, I cannot reveal because of spoiler issues.

When James agreed to publish the short novel in Collier’s Weekly in 1898, he specifically contracted to give them a “ghost story.” He took a number of hints from the Gothic tradition, and alludes to both Charlotte Bronte’s Jane Eyre and Anne Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho, but his chief interest was the ghosts and the horror they invoke. James’ first readers saw nothing in the text beyond a classic horror story, and even contemporary readers are often struck first by the tale’s horror. Stephen King, no stranger to horror fiction, wrote in a 1983 survey of the genre that the only two great supernatural horror stories of the past century (i.e., 1883-1983) had been Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House and Turn of the Screw.

Later on, though, readers and critics began to pay a lot more attention to the narrator’s own voice (and by narrator I mean the governess), likely under the influence of Freudian thought. As early as 1918, Virginia Woolf wrote that Jessel and Quint had “neither the substance nor independent existence of ghosts,” but represented the young governess’s own developing realization of the very real presence of evil in the world. By the 1930s (particularly under the influence of scholar Edmund Wilson) it had become common to see the ghosts as hallucinations, and to see the governess, as the sheltered and repressed daughter of a country parson, as having these visions of the notoriously erotic couple because of her own sexual repression. Later feminist scholars have objected to Wilson’s analysis, and it’s hard to accept his Freudian reading whole hog. Still, James clearly incudes hints in the novel intended to make us wonder about the governess’s sanity. At one point, declaring her intention to stand between the children and their ghostly companions, she declares

I began to watch them [the children] in a stifled suspense, a disguised excitement that might well, had it continued too long, have turned to something like madness. What saved me, as I now see, was that it turned to something else altogether. It didn’t last as suspense—it was superseded by horrible proofs.

But to accept the ghosts as real, you have to find a way to explain away the fact that no one but the governess can see the ghosts. And if you accept the governess as mad, then how do you explain the undeniable terror her sightings of the ghosts evoke? But there is nothing concrete there. We never actually know what the governess thinks may be going on between the ghosts and the children. At one point, when Miles seems to be reading aloud to Flora, the governess insists

“He’s not reading to her,” I declared; “they’re talking of them—they’re talking horrors! I go on, I know, as if I were crazy, and it’s a wonder I’m not. What I’ve seen would have made you so; but it has only made me more lucid, made me get hold of still other things.”

So we’re not sure what those “horrors” are, but perhaps we, too, are as crazy as she is, and the madness is the result of, not the cause of, the horrors we imagine. In his preface to the 1908 edition of the text, James wrote that he wanted the reader to “think the evil, make him think it for himself,” just as the governess thinks it for herself. James has given us a world full of ambiguity, in which the horror is in our own minds, just as it is in the governess’s. This is masterly done, and I’d be hard put to name another text that creates and uses ambiguity as well.

The Turn of the Screw has been adapted several times, for stage, screen, and television. Almost certainly the best of these adaptations is the 1961 film entitled The Innocents, which starred Deborah Kerr as the governess. This film has the further distinction of having a screenplay by Truman Capote, who made it quite clear he believed the ghosts were real. It’s an adaptation worth watching for the sake of the horror, but the ambiguity of the novel is largely lost. So be sure to read the book so you can be less clear about what actually happens.