Order Tramadol 50 mg There is no question that James Joyce is the most significant and influential English language writer of the twentieth century. As the preeminent stylist in English, with the uncanny ability to adopt style to situation, the premiere example of the use of “stream of consciousness,” the creator of a new kind of short story that relied on a climactic “epiphany,” Joyce is the author who made Virginia Woolf, William Faulkner, Samuel Beckett, and many others possible. The conventional wisdom accepts Ulysses as Joyce’s greatest work: It was ranked as number 1 in Modern Library’s famous 1998 list of the top English language novels of the twentieth century. It appears as well on the Guardian list of greatest novels in English, the Observer’s list of greatest world novels, and Penguin’s list of the hundred favorite novels as selected by their readers. It appeared, as well, on the 2002 list of the “100 Greatest Books of World Literature” compiled by Norwegian Book Clubs in conjunction with the Norwegian Nobel Institute. On the “Greatest Books of All Time” web site, which presents an amalgam of 291 different “Great Books” lists world-wide, Ulysses ranked as the second English language novel (coming in right behind The Great Gatsby).

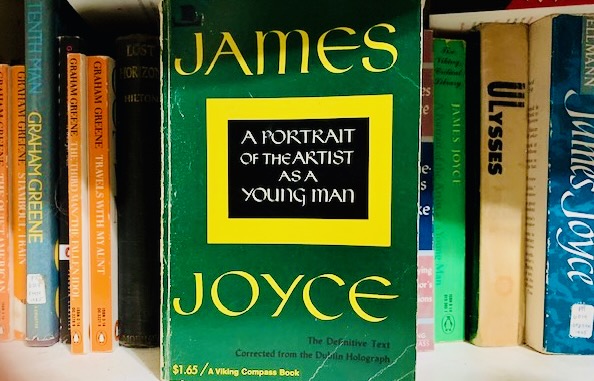

And so of course it would have been the expected thing for me to include Ulysses on my list as the obvious Joyce choice. Once again, though, I defy the expected and am naming A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man as number 51 on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.” Please note the name of my list. I am not claiming that Portrait is a greater novel than Ulysses. I know I am outvoted there. But the idea of “greatness” is subjective, as all these kinds of lists are. And recall that from the beginning I said that I would not put on my list any novel, despite its reputation, that I felt was more of a chore than a joy to read. Great as it is, Ulysses is a huge chore, not only because of its great length (988 pages in the standard edition) and its heavy and sometimes obscure allusiveness, but for its radical experimentation with language in each new scene. Many people love the intellectual game of reading Ulysses, but I think I speak for most people when I say that the necessity of having a book almost as long as the original to explain the original makes the reading quite a chore. Portrait of the Artist, however, though it has its own difficulties, does not require the same intensity of commitment, and is vastly rewarding in its own right. It also appears on the Modern Library list and on the Penguin readers’ list, and comes in at number 45 among English language works on the Greatest Books of All Time list.

Portrait of the Artist is a semi-autobiographic Bildungsroman—that is, a “coming of age” novel taking the protagonist from childhood into adulthood in the same vein as, say, David Copperfield or Ellison’s Invisible Man. What Joyce did, however, was abandon the first person narration typical of such novels—which generally depicted the narrator as the protagonist grown up and looking back from that adult perspective on his youth and young adulthood—and replaced it with what is generally called “free indirect discourse.” This style Joyce learned from Flaubert, whom he greatly admired. In free indirect discourse, a writer uses a third-person narrator, but one that expresses a character’s first-person thoughts. The style is “free” because it is not limited to a single character, e.g. the protagonist, but can range among different characters. Thus the subjectivity of a character’s thoughts is expressed through a third person narrator, and at the same time the character’s ideas are distanced slightly from the reader through the third person narration. In Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist, the third person narrator’s voice changes and matures through the five long chapters of the novel, reflecting the protagonist Stephen Dedalus’s maturing consciousness, at the same time expressing Stephen’s thoughts and emotions as he is having them, not from a David Copperfield-esque perspective of completed maturity. The narrator has essentially disappeared among the thoughts and impressions of his characters. Stephen himself expresses this aesthetic ideal in the novel’s last chapter, when he declares that “The artist, like the God of the creation, remains within or behind or beyond or above his handiwork, invisible, refined out of existence, indifferent, paring his fingernails.”

This technique is manifest from the beginning of the novel, told in language appropriate for Stephen as the toddler he is in these opening pages, but still in third person:

Once upon a time and a very good time it was there was a moocow coming down along the road and this moocow that was coming down along the road met a nicens little boy named baby tuckoo…

His father told him that story: his father looked at him through a glass: he had a hairy face.’

He was baby tuckoo.

In the second chapter, the maturing adolescent Stephen dreams of the epiphany of consummated love, in language appropriate to the character’s age, idealizing romantic love with religious terminology:

And in that moment of extreme tenderness he would be transfigured. He would face into something impalpable under her eyes and then, in a moment, he would be transfigured. Weakness and timidity an inexperience would fall from him in that magic moment.

In the third chapter, where a slightly older Stephen undergoes a spiritual awakening that wrenches him from the debauched life he has begun to lead, In words just as romantic as in the previous chapter had been applied to love, Stephen glories in his redemption:

He had confessed and God had pardoned him. His soul was made fair and holy once more, holy and happy.

It would be beautiful to die if God so willed. It was beautiful to live if God so willed, to live in grace a life of peace and virtue and forbearance with others.

In chapter four, Stephen contemplates joining the Jesuit order, as some of his masters are urging him to do. But by now he has begun to grow away from the Church, and is attracted instead to aesthetic beauty, and to a career in literature. The climax of this decision occurs in the moment of epiphany that ends the fourth chapter, when he is transfixed by the vision of a young woman wading in the sea, in “the likeness of a strange and beautiful seabird”:

She was alone and still, gazing out to sea; and when she felt his presence and the worship of his eyes, her eyes turned to him in quiet sufferance of his gaze, without shame or wantonness….

Her image had passed into his soul for ever and no word had broken the holy silence of his ecstasy. Her eyes had called him and his soul had leaped at the call. To live, to err, to fall, to triumph, to create life out of life!

The growth of the artist, from dedication to Love, to God, and ultimately to Art, has been the theme of these chapters, and Joyce’s words have presented the consciousness of the protagonist at each stage. In the fifth and final chapter, Stephen, now at University, can be seen transcending his previous interests—family, country, Church, Ireland itself—and the language reflects that growth. He sees himself here as “a priest of eternal imagination, transmuting the daily bread of experience into the radiant body of everliving life”—one definition of “the artist.” Later, talking with his friend Cranly, he relates a quarrel with his mother over celebrating Easter. Why not do this simple thing for his mother? Stephen’s answer, “I will not serve,” is, theologically, Lucifer’s response to his duty to God, which results in his expulsion from Heaven. Stephen, having decided he must leave Ireland to become the writer he was meant to be, speaks in the last few pages of the novel in his own voice rather than through free indirect discourse, but the language comes from his diary and not from the commenting perspective of the later writer—and it sounds much like the language of this last chapter, full of the confidence and idealism of youth:

O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race.

I don’t mean to give the impression that the book is solely about language and style, but that is clearly one of the revolutionary aspects of this novel. It can certainly be read also as a reflection of, and response to, the historical situation of Joyce’s childhood and youth. The dramatic Christmas dinner scene that occupies so vivid a part of young Stephen’s life in chapter one pits Dante Riordan, Stephen’s intensely Catholic governess, against Stephen’s father and his friend, Mr. Casey, who support the Irish nationalist Charles Parnell and blame the Church for “hounding” him to his death over an affair he was caught in. Pressured by both sides—Church and state—and by the petty bourgeois interests and morality of his family, Stephen by successive degrees embraces and rejects all of these interests, and concludes that he cannot be a free artist under the constraints of Irish society, and opts to fly from his home to Paris in the end. (No, this is not a “spoiler.” Portrait is not a plot-driven novel, and one reads it not to see how the plot turns out but to see how Stephen gets from point A to point B. And C and D.). The flight to Paris largely explains Stephen’s name—Dedalus—the hero of Greek myth who fashioned wings that he used to escape the trap of the labyrinth. Stephen, too, flies from his own entrapment. The end of the novel leaves open whether his flight will be successful, like that of Dedalus, or disastrous, like that of Dedalus’s son Icarus, who flew too close to the sun and crashed.

Joyce began writing his first novel in 1904, two years after he had himself left Dublin for Paris. He called it Stephen Hero, which he projected would be a 63-chapter autobiographical novel told in a realistic style through a third-person omniscient narrator. In 1907, after completing 25 chapters and more than 900 manuscript pages, Joyce abandoned this approach and decided to condense the story into five long chapters, using free indirect discourse and an approach more subjective than strictly realistic. By 1911, Portrait was nearing completion, but Joyce was frustrated by his inability to find a publisher for his short story collection Dubliners, and he threw the manuscript into the fire. Fortunately, it was rescued. In 1913, W.B. Yeats sent one of Joyce’s poems to Ezra Pound, who was editing an anthology of “imagist” poetry. Pound liked what he saw, and wrote to Joyce directly, encouraging his progress on Portrait. It was Pound who first published Portrait serially in the journal The Egoist in 1914-15, and also found a New York publisher for the novel in 1916 when Joyce could not find a British publisher interested in the project. The rest, as they say, is history. The initial critical reaction to the book was mixed, but the more perceptive readers saw its greatness. H.G. Wells wrote “one believes in Stephen Dedalus as one believes in few characters in fiction.” Pound himself predicted, accurately, that the novel “will remain a permanent part of English literature.” And so it has.