Here’s a trivia question for you: Who is the best-selling British author over the past 35 years whose name is not J.K. Rowling? Give up? It’s Terry Pratchett, author of the popular Discworld fantasy series, who has sold well over 100 million books and has been translated into 43 languages. Pratchett was the best-selling UK author of the 1990s, but you may have had some difficulty answering the trivia question if you’re an American, because he was far less well known in the U.S., at least until 2005 when he finally cracked the New York Times best-seller list. But Pratchett’s 41 Discworld novels comprise one of the most popular and substantial fantasy series ever composed, and Pratchett writes at a consistently high level from The Colour of Magic, his first Discworld novel in 1983, through The Shepherd’s Crown, his last, published posthumously in 2015. If you don’t believe that, consider the BBC’s famous “Big Read” contest of 2003, in which they set out to find the UK’s favorite book, and ended up counting three quarters of a million votes. When they published the results, five of Terry Pratchett’s novels appeared in the top 100 favorite books, and fifteen in the top 200—more than any other author.

Pratchett won so many awards and honors for his Discworld books that I don’t have time or space to list them all. But here are a few: He won the British Science Fiction Award in 1989 and the British Book Awards’ “Fantasy and Science Fiction Author of the Year” for 1994. He won the U.K. Carnegie Medal for the year’s best children’s book for 2001, and won the Locus Award for Best Young Adult book for 2004, 2005, 2007, and 2016. He won the Andre Norton Award from the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America in 2010, the World Fantasy Award for Life Achievement in 2010 and the American Library Association’s Margaret A. Edwards lifetime achievement award for his “significant and lasting contribution to young adult literature.”

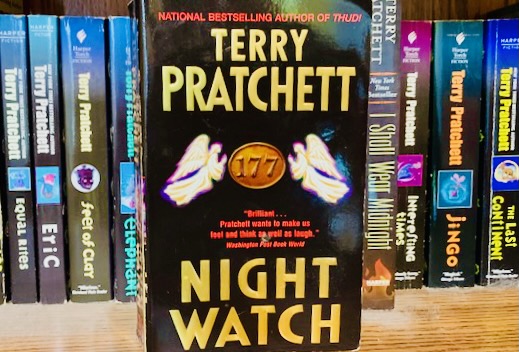

If you’ve been following my list of the 100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language so far, you can probably see my dilemma with Terry Pratchett. That is, he’s got 41 Discworld novels,15 of which are on the BBC list of favorite novels. So how do I pick just one? Well, I did, but I think I have got to admit, in some ways this one book stands in for all of them. I’m picking the 29th Discworld novel, Night Watch—a book that was listed as number 73 on the BBC “Big Read” list. Night Watch also appears as number 48 in the Guardian’s list of the “100 Best Books of the 21st Century.” It also won the 2003 “Prometheus Award” given by the Libertarian Futurist Society for an anti-authoritarian science fiction or fantasy novel. And it appears as number 69 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

So, before talking about Night Watch in particular, I’m thinking some of you might need an introduction to Discworld itself. Discworld is a large disc—an actual flat earth—that moves through space like other planets around its own sun while resting on the backs of four giant elephants, who are standing on the back of a super-giant turtle named Great A’Tuin as he swims through space. Several places in Discworld serve as settings for the novels, including the Ramtops region, where the Lancre coven of witches live (featuring most significantly Granny Weatherwax and, in later YA novels, witch trainee Tiffany Aching), and which serves as home for eleven of the novels. But the most common setting is the city state of Ankh-Morpork, a walled city five miles in diameter, which is the home of Unseen University and its wizards, the Patrician ruler of the city Lord Vetenari, and most importantly the City Watch and its commander Samuel Vimes, who form the subject of Night Watch as well as five previous Discworld novels, and two more that will follow. Let me say at the outset that already having read the five previous City Watch novels will enhance your enjoyment of Night Watch, but if you’re only going to read one of the Discworld novels to see if you like it, you’re not going to feel at sea beginning with this one.

Night Watch begins on May 25, which is the 30th anniversary of what Ankh-Morpork celebrates as the “Glorious Revolution,” and is also not coincidentally the anniversary of the death of John Keel, the man Sam Vimes (now commander of the Guard) remembers as his hero and mentor from his early days in the police force. On this day, Sam’s new wife is about to have their first child, but Vimes is pursuing a dangerous criminal named Carcer, who has killed a number of Watchmen. He has cornered Carcer on the roof of Unseen University when a powerful storm erupts, and Vimes is knocked out by a kind of magical lightning bolt. When he comes to, he realizes he’s been sent back in time 30 years.

Vimes hopes to get help from the wizards of Unseen University to restore him to his own time (after all, he’s about to become a father), but before he can do anything he is arrested for breaking curfew by a very young officer of the Guard named Sam Vimes. He’s put into a cell next to the murderer Carcer, who has also traveled in time as a result of the lightning strike. Upon his release, the sociopathic Carcer joins the Cable Street Particulars (generally known as the Unmentionables), essentially the Gestapo serving the city’s ruler Lord Winder—remembered by Vimes as “Homicidal Lord Winder,” whom Vimes knows is destined to be overthrown in the soon-to-come Glorious Revolution, and be replaced by the Patrician who will be known as Mad Lord Snapcase.

Time stands still for a moment through the intercession of Lu-Tze, the “history monk” who has appeared in a few earlier Discworld novels, and the monk tells Vimes that he and Carcer have been involved in a “major temporal shattering,” and that Carcer has killed the Guard Sergeant at Arms John Keel, who was due to arrive that day and take command of the Watch House at Treacle Mine Road. As a result, Lu-Tze says, Vimes must take Keel’s place and pretend to be him for history to turn out as it must.

When the revolution begins, Vimes (masquerading as Keel) takes charge of the Watchmen in the Treacle Mine Road area of the city, and keeps his younger self with him as much as possible in order to teach him how to be an effective cop. His men are able to neutralize the Unmentionables’ headquarters, and essentially ally themselves with the revolutionary citizens in a mutually beneficial arrangement that keeps the peace behind the barricades, which are set up to prevent fighting between the rebels and the military. His men gradually push the barricades further and further until Vimes and his Watchmen are in control of a large section of Ankh-Morpork, a section that includes much of the city’s food supply, and is christened “The Glorious People’s Republic of Treacle Mine Road.”

The revolt ends when Homicidal Lord Winder is eliminated by a young assassin named Vetinari (who will prove important in the subsequent history of Ankh-Morpork). But the new Patrician, Mad Lord Snapcase, is jealous of the admiration that “Keel” has enjoyed by keeping his section of the city peaceful through the uprising, and dispatches Carcer with his Unmentionables to terminate Keel/Vimes with extreme prejudice. And there’s where I’ll have to leave it if I don’t want to engage in a major spoiler event.

More than many of the earlier novels in the Discworld series, Night Watch is a “black humor” novel, or, as Pratchett himself said, it contains “the humour that comes out of bad situations.” There is nothing funny about the kind of torture that the “Unmentionables” of the novel engage in, nor about the sort of despots who utilize such methods. The power mongering and paranoia displayed by the “Homicidal” and the “Mad” are humorous in the exaggerated way they act, but it’s a grim humor when we reflect how close it really is to reality. But responding to the comments of critics who called Night Watch a “dark” book, Pratchett said “I am kind of puzzled by the suggestion that it is dark. Things end up, shall we say, at least no worse than they were when they started… and that seems far from dark to me. The fact that it deals with some rather grim things is, I think, a different matter.”

Despite the grimness, Night Watch is still full of the kind of snarky humor that characterizes all the Discworld novels. There’s a good laugh on virtually every page. Even when Vimes makes an arrest or is questioning a suspect, the laughs are there, as in this exchange:

“No! Please! I’ll tell you whatever you want to know!” the man yelled.

“Really?” said Vimes. “What’s the orbital velocity of the moon?”

“What?”

“Oh, you’d like something simpler?”

Or this one:

“I get it,” said the prisoner. “Good Cop, Bad Cop, eh?”

“If you like.” said Vimes. “But we’re a bit short staffed here, so if I give you a cigarette would you mind kicking yourself in the teeth?”

And occasionally, Pratchett will even put in a deliberate groaner, like this one, in which the working-class Vimes chafes in his high-class ceremonial armor:

But the helmet had gold decoration, and the bespoke armorers had made a new gleaming breastplate with useless gold ornamentation on it. Sam Vimes felt like a class traitor every time he wore it. He hated being thought of as one of those people that wore stupid ornamental armor. It was gilt by association.

But Night Watch goes deeper than the jokes. It’s about what a copper’s job is and is not—a message that seems particularly applicable in a post-George Floyd, “Black Lives Matter” world: Filtered through Vimes’ mind, “what is a copper’s job?”

What is a copper’s job? Keep the peace. That was the thing. People often failed to understand what that meant. You’d go to some life-threatening disturbance like a couple of neighbors scrapping in the street over who owned the hedge between their properties, and they’d both be bursting with aggrieved self-righteousness, both yelling, their wives would either be having a private scrap on the side or would have adjourned to a kitchen for a shared pot of tea and a chat, and they all expected you to sort it out.

And they could never understand that it wasn’t your job. Sorting it out was a job for a good surveyor and a couple of lawyers, maybe. Your job was to quell the impulse to bang their stupid fat heads together, to ignore the affronted speeches of dodgy self-justification, to get them to stop shouting and to get them off the street. Once that had been achieved, your job was over. You weren’t some walking god, dispensing finely tuned natural justice. Your job was simply to bring back peace.

This theme expands to include the question of what the illegitimate uses of the police are. These include the arrest and torture of people not sympathetic to the current regime—those represented in the book as the Unmentionables. Honest policing is not a tool of politics. Nor is it legitimately a tool for keeping certain people in their place. But Vimes/Pratchett have one more theme this novel makes clear. Put simply, as it is in the book:

Don’t put your trust in revolutions. They always come around again. That’s why they’re called revolutions.

It’s clear in Night Watch that Mad Lord Snapcase is going to be no better than the Homicidal Lord Winder he replaces, as he immediately dispatches the Unmentionables to eliminate the hero of the hour who might not be a strong supporter of the new order.

So is Pratchett simply cynical, believing that things will never get better? Well, no. Throughout the Discworld series, progress is made on many fronts. But new problems always arise. People are always going to be people. They often do the best they can, which sometimes is just wrong. When they know better, they will do better. Some of them.