After the towering critical success of his first three novels, Thomas Pynchon was being considered by some, in the 1970s, as America’s greatest living writer. It’s true that, like his fellow early post-modernist John Barth, his reputation has declined significantly over the past forty years or so—though perhaps not as precipitously as Barth’s since his 2009 post-modern detective novel Inherent Vice was well received and turned into a popular star-studded film by Paul Thomas Anderson in 2014. But Pynchon’s best-known and most highly-acclaimed novel is his behemoth 800-page 1973 book Gravity’s Rainbow. I was in graduate school at the time it came out, and I seriously remember my fellow Ph.D. candidates discussing whether this was the greatest American novel since World War II. Pynchon’s third novel won the 1974 National Book Award (sharing it with Nobel laureate Isaac Bashevis Singer’s A Crown of Feathers and Other Stories). And Gravity’s Rainbow was a unanimous choice for the 1974 Pulitzer Prize. But, with an autocracy recalling the days of Sinclair Lewis, the Pulitzer board rejected the jury’s choice, calling Pynchon’s novel “turgid,” “overwritten,” “obscene” in places, and generally “unreadable.” Consequently, no Pulitzer Prize for fiction was awarded in 1974.

Now there is nothing obscene about Gravity’s Rainbow, and while the novel may well be one of the most significant works of fiction of the second half of the twentieth century, and while it probably should have been awarded the Pulitzer in 1974, I find myself agreeing with one aspect of the Pulitzer board’s opinion: I find the novel darn near unreadable. It is incredibly complex and seems like a great chore to read. Whenever I put it down I had to psych myself up to pick it up again. Perhaps this can be a lovable book for somebody. But it wasn’t for me.

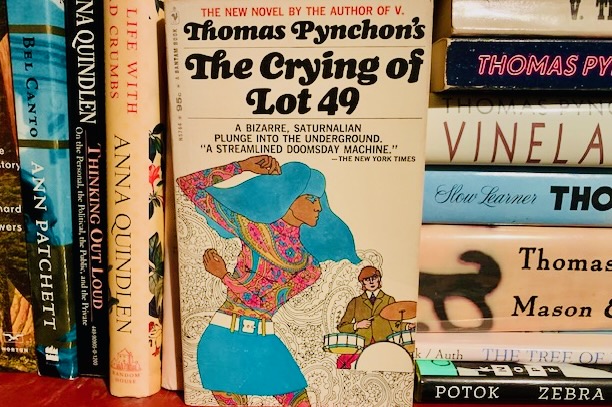

But there is a silver lining here. You can get most of what is lovable in Pynchon’s writing—the dark humor, the cleverness, the allusiveness, the flavor of the late sixties society plus the social critique, in Pynchon’s far shorter second novel, The Crying of Lot 49. This 1966 novel does appear on Time magazine’s list of the 100 greatest English novels since 1923, and I’m including it here as number 71 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

The novel’s protagonist is Oedipa Maas, a suburban housewife in Kinneret-Among-The-Pines, California, who is married to disk jockey and former used car salesman Mucho Maas, a fellow with a taste for teenaged girls (a la Lolita’s Humbert Humbert, Nabokov having been an early influence on Pynchon). She also has a therapist named Dr. Hilarius, who keeps trying to get her to experiment with LSD. Oedipa learns that she has been named executor of the estate of her fabulously wealthy former lover, Pierce Inverarity. And this begins a crazy whirlwind of a mystery that gets more and more complicated the deeper she delves into it.

She drives to Pierce’s home town, San Narcisso, where she checks in to the Echo Courts Motel and meets Pierce’s lawyer and fellow executor named Metzger, a former child movie star. She fairly quickly begins an affair with him, one that is spied upon by a wannabe rock group at the motel called the Paranoids. Later at a bar, Oedipa sees a curious graffiti symbol that looks like a muted trumpet, and labeled “W.A.S.T.E.” She also learns that Inverarity may have had connections to the Mafia, and had been trying to sell the bones of American soldiers from the Second World War to a tobacco company to be used as charcoal. This reminds one of the Paranoid groupies of a Jacobean Revenge Tragedy she recently saw called The Courier’s Tragedy. Struck by the coincidence, Oedipa goes to a performance of the play, and is struck by a reference to an organization called “Tristero.” She wants to learn what the name refers to, but the play’s director, Randolph Driblette, doesn’t know, or is not forthcoming.

Oedipa witnesses more images of the muted horn, and discusses these occurrences with a right-wing paranoid historian she meets named Mike Fallopian, who suspects there is a widespread conspiracy. Oedipa begins to examine Inverarity’s extensive stamp collection, and begins to suspect the same thing. She learns that the post-horn was on the coat of arms of a European postal service called Thurn and Taxis, an organization that monopolized all postal service and was able to suppress all competition. One such competing service was called Tristero, an organization quashed centuries before, but seems to have been driven underground. But Oedipa sees that some of Pierce’s stamps are foreries showing a muted post-horn. She comes to believe that Tristero still exists as a secret organization bent on undermining not simply the post office but American society in general. W.A.S.T.E., she finds, stands for We Await Silent Tristero’s Empire.

Oedipa cannot be sure that she is not simply paranoid, imagining the connection among all these clues, or whether all these Tristero clues are some kind of elaborate hoax that Inverarity put together just to mess with her mind after he was dead. Or whether she is in fact on to something. The novel ends as she, along with a learned philatelist named Genghis Cohen whom she has enlisted for his advice, attend an auction of Inverarity’s private possessions, including his stamp collection, included in auction Lot 49. Will the buyer be someone who can tell her more about Tristero?

The novel opens up a window into the America of 1966; indeed, in the book’s first paragraph, Oedipa is returning home from a Tupperware party. With its invocation of the Beatles in the air (the Paranoids have “Beatle haircuts” and sing with British accents), experimentation with drugs (especially LSD), the “free love” atmosphere that gratuitously leads Oedipa into bed with Metzger, and most cogently the existence of a counterculture that may or may not include the Tristero organization, the novel is very much reflective of its time. But at the same time Pynchon seems enthralled by influences from the past, particularly Classical mythology. Oedipa, of course, is the feminine form of Oedipus, a clear signal that we are to view Oedipa as a solver of riddles—though remembering that Oedipus’s ability to solve riddles, to probe mysteries, ends up disastrously for him. San Narcisso and the Echo Courts Motel allude of course to the myth of Narcissus, who falls in love with his own reflection and dies pining for it. In the novel, Oedipa encounters a number of mirrors—in her room at the motel, in a dream in which she wakes to find herself staring into a mirror, and elsewhere. These images may suggest a kind of paranoia, a suggestion that all her suspicions are coming from herself. Other characters have allusively classical names: Dr. Hilarius has a name from the Latin for “cheerful” (an emotion apparently drug induced) while John Nefastis (whom I’ll discuss further below) has a name that means “contrary to divine law.” “Pierce Inverarity” seems a name that suggests piercing through an untruth—Oedipa’s challenge throughout the novel.

The book is, obviously, highly allusive. But I’d like to talk about three of the most effective allusive scenes in the novel. In the first chapter, Oedipa recalls visiting an art museum in Mexico City, where she was deeply moved by a painting by the Spanish Surrealist Remedios Varo, entitled “Embroidering the Earth’s Mantle” (Bordando el Manto Terrestre). In the painting, six maidens imprisoned in a tower perpetually weave a giant tapestry, which flows out of the windows of the tower, filling the void outside.

A kind of tapestry which spilled out the slit windows an into the void, seeking hopelessly to fill the void: for all the other buildings and creatures, all the waves, ships and forests of the earth were contained in this tapestry, and the tapestry was the world.

As the novel develops Oedipa, like the women in the tower, cannot be sure whether the world outside the tower of her own consciousness actually exists, or is the product of her own embroidering mind.

A second deeply significant section of the novel is Pynchon’s description of the Revenge play The Courier’s Tragedy by Jacobean playwright Richard Wharfinger. The play is, of course, a construction of Pynchon’s imagination, and Wharfinger totally fictitious, but as described it is a hilariously informed parody of actual plays by Webster, Tourner, Middleton, and John Ford. Pynchon gives a blow-by-blow summary of the play as Oedipa watches it, complete with quotations when they seem appropriate. The first at ends with an avenger named Ercole tearing out the tongue of a faithless confidante, impaling it on his rapier and then setting fire to it, madly crying out

The pitiless unmanning is most meet

Thinks Ercole the zany Paraclee.

Descended this malign, Unholy Ghost,

Let us begin thy frightful Pentecost.

Part of the grisly humor here stems from the fact that this is actually not much of an exaggeration of what goes on in Jacobean Revenge tragedies. Consider the last act of Ford’s ’Tis Pity She’s a Whore, in which the protagonist enters from offstage with the heart of his lover (who was also his sister) impaled on the end of his sword. But the importance of The Courier’s Tragedy to the plot of the novel is that the name Trystero is first mentioned in the play, and it strikes fear into th members of the cast. But Oedipa, exploring the text of the play, discovers that the name is mentioned in only one variant of the text, and that the use of it, and the characters’ reactions to it, were chiefly the product of the director’s imagination. Is her discovery of the Tristero conspiracy a similar construction?

Thematically, perhaps the most important section of the book, although it is a scene that gives Oedipa no help at all in her investigation and doesn’t forward the plot in any way, is her encounter with John Nefrastis. She has learned about “Maxwell’s Demon,” a 19th-century thought experiment by which James Clerk Maxwell had tried to disprove the Second Law of Thermodynamics. That Second Law deals with the concept of entropy, the measure of the amount of disorder in a physical system, and holds that in a closed system, entropy cannot decrease over time (a correlation proposed by modern science is that the universe, being a closed system, must eventually die in a state of maximum entropy). We may exert force to put things in order, but in using up energy we only contribute to the eventual increase of entropy. Nefrastis (who true to his name denies the “divine law” of entropy) has created a machine containing Maxwell’s Demon, who in the thought experiment sorts out molecules in a particular without exerting energy. Of course, it can only work if Oedipa is a “sensitive,” able to telepathically communicate with the demon in the machine. Shockingly, it doesn’t work.

The episode works, however, as a symbol in the novel: Oedipa herself is serving the role of Maxwell’s demon in the novel, in San Narciso, in America itself. She is trying to reverse the entropy that is breaking down the order of society, trying to create order out of the disorder deliberately being wrought by Tristero. Silent Tristero’s Empire will be the ultimate downfall of the ordered society we experience. If the Second Law of Thermodynamics is truly law, then any order Oedipa may restore can only be temporary.

In the end, like most post-modern texts, The Crying of Lot 49 is characterized by paranoia in the face of technology and late-stage capitalism, self-reflexiveness, and particularly indeterminacy, As readers of the novel, we mirror the quest of Oedipa for meaning And like Oedipa, we can’t be sure, ultimately, that there is any, or that it will make sense if we do find it.