https://oleoalmanzora.com/oleoturismo-en-pulpi/ Before his death in 2018 at the age of 85, Philip Roth had for decades been touted for the Nobel Prize in literature. As one of America’s most prolific and highly regarded novelists, and a favorite of odds-makers projecting the award’s winners, Roth had a right, or at least a hope, to expect the award year after year. But when the award went to an American in 2016, it was not Roth but the surprise recipient Bob Dylan who walked away with the prize. Those closest to Roth knew how embittered he was at not receiving the honor, so that he began to call the Nobel the ”Anybody but Roth” award.

But Roth had a reputation for pushing boundaries, for stirring up controversies, and for objectifying women in his works, so in some ways it’s not surprising that the Swedish Academy found it more politic to steer clear of any Roth furor. Besides, Roth had already won so many awards in his life that the Nobel would have been, well, kind of redundant.

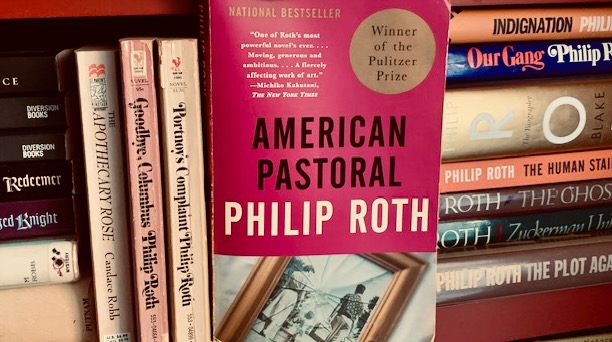

Let me do a quick survey of just a few of Roth’s most significant honors: His first book, Goodbye, Columbus, won the National Book Award in 1960. He won a second National Book Award for Sabbath’s Theater in 1995. In between, he had been a finalist for the National Book Award four other times (for My Life as a Man in 1975, The Ghost Writer in 1980, The Anatomy Lesson in 1984, and The Counterlife in 1987). He won the National Book Critics Circle Award for TheCounterlife (1986) and for Patrimony (1991). He won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Operation Shylock (1994), The Human Stain (2001) and Everyman (2007), and he won the WH Smith Literary Award for The Human Stain (2001) and for The Plot Against America (2005). He won Britain’s Man Booker International Prize for his body of work in 2011. As for America’s most prestigious prize, the Pulitzer, Roth was a finalist three times—for The Ghost Writer (1980), Operation Shylock (1994) and Sabbath’s Theater (1996) before finally taking home the award for American Pastoral in 1998.

For my own list of Most Lovable Books, there was a bit of a dilemma in choosing one of Roth’s novels—even if I limited myself to novels others had found worthy of honoring, I had a good dozen to choose from. But I really only had one book in mind, and was happy that other list-makers mostly agreed with me on this. Roth’s Pulitzer winner, American Pastoral, appears on Time magazine’s famous list of the hundred greatest English language novels since 1923. It is also named in the Observer’s list of the 100 greatest world novels. The “Greatest Books of All Time” website, with its aggregate list of more than 300 such “Great Books” lists, names Roth’s early satire Portnoy’s Complaint in its top 100 novels in English, but lists American Pastoral as number 154. In 2006, the New York Times Book Review editor surveyed hundreds of prominent writers, critics and editors, asking them to identify “the single best work of American fiction published in the last 25 years.” The winner was Beloved, but Roth’s American Pastoral came in as number 5. After Roth’s death in 2018, Stephen King wrote that American Pastoral was Roth’s greatest novel: “American Pastoral is one of the five best novels I have ever read, maybe the best.…The scope is relatively small, but the ambition is epic. Few can handle the passing years as well as Roth does here. It ranks with the greatest of American fiction.”

American Pastoral is the story of a Jewish businessman from an upper middle-class family in Newark, New Jersey: Seymour “Swede” Levov, former star athlete from Weequahic High School, who married a former Miss New Jersey, inherited his father’s glove making business, and seemed to be living the perfect idyllic American life. Until disaster struck.

The novel’s narrator is Nathan Zuckerman (often used, here and in other novels, as the alter ego of Roth himself). At a 45th high school reunion (in 1995), Zuckerman runs into his former close friend, Jerry Levov, younger brother of the popular athlete Seymour, nicknamed “Swede” because of his Nordic appearance—his blond hair and blue eyes. Jerry tells Zuckerman about the sad demise of his brother, once Zuckerman’s high school idol, who has recently died of prostate cancer. Zuckerman takes what scraps he has—his conversation with Jerry, two encounters he had himself with the “Swede” in the years since high school (the last one quite recently at the Swede’s invitation, to try to get Zuckerman to write Swede’s father’s story), and some newspaper articles—and decides to try to put together the story of the Swede’s own unhappy life.

The Swede’s father, Lou Levov, was a very successful glove manufacturer in Newark, and the Swede grew up expecting, and expected, to take over the factory. He joins the Marines in 1945 and becomes a drill instructor, then heads for college where he meets his future wife, Dawn Dwyer, the former Miss New Jersey from Elizabeth. He marries the beauty queen, has a daughter with her, and begins to manage his father’s business. He moves to an impressive house in the rural Old Rimrock, and for all intents and purposes seems to be living the pastoral American dream.

But as the 1960s begin, the American dream has begun to show its cracks. Racial unrest begins to tear apart inner cities, and the Newark neighborhood where the Levov factory is located is particularly hard hit. On a more personal level, the Swede’s teenaged daughter Meredith (known as “Merry”), suffering since early childhood from an enervating stutter, becomes more and more radicalized by the U.S. war in Vietnam, and one night in February 1968 plants a bomb in the Old Rimrock post office (the only Federal building in town), destroying the building and killing a doctor who by chance had been in the building at the time. Merry goes into hiding, and no one seems to be able to help Seymour and Dawn find her or speak to her. After four months, a suspicious woman named Rita Cohen visits Seymour at his factory, feigning interest in the glove-making process, but later claiming that she has come from Merry, and hits him up for money which she says will go to his daughter.

After five years, Seymour finds his daughter living in squalor in Newark’s inner city. She refuses his help, and seems to relish his horror when she tells him she has been responsible for other bombings and three other deaths. But now apparently she has become an extreme Jainist ascetic, to whom all life is sacred, even the bacteria she might destroy is she ever washes. The Swede persistently refuses to believe the worst of her, and continues to tell himself her worst actions were manipulated by Rita Cohen and others of her ilk. Around the same time, at an eventful dinner party that closes the novel, Seymour discovers that his wife is having an affair, that Merry’s former speech therapist has some secrets of her own, that in fact everyone he knows, he comes to believe, has an outward personality that conceals an inner iniquity. The American dream, the American “pastoral” (in the literary sense of an idealized version of reality), is undercut in Seymour’s mind by the unredeemed chaos of modern life. In the end, through its focus on the rise and fall of one American family, the novel reflects the American experience of optimism dissolving into disillusionment from the 50s through the 70s.

This is essentially the theme of the novel. The period covered by the action—from the late 1940s to the early 1970s—is presented (ostensibly by Zuckerman) as a fall from innocence into a chaotic world in which all the old certainties are gone. Roth puts this history into a kind of mythic framework, labeling the three parts of the novel “Paradise Remembered,” “The Fall,” and “Paradise Lost”—alluding, of course, to Genesis and to John Milton. The Swede’s Paradise was the immediate post-war period as he assembled his ideal family and their idyllic home. It was a world of order and unity and what for him seemed the nation’s unified sense of purpose. The Fall for American society came with the civic unrest and social upheaval of the 1960s, embodied for the Swede in his perfect daughter’s turn to violent protest. Paradise Lost for the Swede is his life after the bombing. He spends the rest of his life trying to make sense of it, trying to see exactly what he did wrong in raising Merry that led to her into terrorism, what he did wrong in his marriage that led Dawn to the affair that breaks up their conjugal bond and sends him looking to start over. He is never able to find a satisfactory answer. When he finds Merry and talks to her, he comes to realize that the cause of her actions is finally impossible for him to find. The novel suggests this is because there simply isn’t one. As Roth, or Zuckerman, asserts at one point, “There are no reasons. She is obliged to be as she is. We all are. Reasons are in books.” And furthermore,

He had learned the worst lesson that life can teach—that it makes no sense. And when that happens the happiness is never spontaneous again. It is artificial and, even then, bought at the price of an obstinate estrangement from oneself and one’s history.

This post-modern conclusion isn’t where the indeterminacy of the novel stops. It is also the dilemma faced by Zuckerman as he tries to tell the story. Did he get the Swede right? Can any writer ever get the character right? As the narrator says,

The fact remains that getting people right is not what living is all about anyway. It’s getting them wrong that is living, getting them wrong and wrong and wrong and then, after careful consideration, getting them wrong again. That’s how we know we’re alive: we’re wrong.

Others are inherently unknowable. Truth is inherently impossible to reach. The Swede’s tragedy is impossible to find an explanation for. Why do the good suffer? In his own Paradise Lost, Milton’s purpose was to “justify the ways of God to men.” Roth is not so ambitious, or so confident. He just raises the question.