By the time Evelyn Waugh published Brideshead Revisited in 1946, he had already published string of novels that established him as the foremost of British satirists writing between the wars. In particular, his Decline and Fall (1928), A Handful of Dust (1934), and Scoop (1938) were considered minor classics in this genre. But what was to come to be considered his greatest novel, Brideshead contained little in the way of satire when it appeared in 1945. It was an immediate best-seller, and in the U.S. was “Book of the Month” for January 1946. Some of Waugh’s literary supporters disliked the book, particularly the ending. The influential literary critic Edmund Wilson wrote that “The last scenes are extravagantly absurd, with an absurdity that would be worthy of Waugh at his best if it were not—painful to say—meant quite seriously.” As it turned out, however, most people did not concur with Mr. Wilson’s assessment, and as time has gone on Brideshead has emerged as Waugh’s best-loved and his most acclaimed work.

The book was included in Time magazine’s list of “All Time Novels” (2005), the New York Public Library’s “125 Books We Love for Adults” (2020), BBC Radio Oxford’s “100 Books You Must Read Before You Die” (2020), and ParadeMagazine’s 2016 list of “The 75 Best Books of the Past 75 Years.” Modern Library’s famous 1998 list if the 100 Best English Language Novels of the 20th Century ranked Brideshead Revisited number 80, and its rival Radcliffe Publishing’s 100 Best Novels in the same year ranked the book 74th. Waterstone’s “Books of the Century” ranked Brideshead number 49, the London Times’ 2022 list of the “50 Best Books of the Past 100 Years” ranked it number 47, and in the BBC’s 2003 “Big Read” survey Waugh’s classic was ranked number 45 by readers. Finally, in the Penguin Publisher’s list of “100 Must-Read Classics, as Chosen by Our Readers,” Brideshead Revisited came in at number 40. And of course it appears here as number 94 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

The novel is subtitled “The Sacred and Profane Memories of Captain Charles Ryder,” and it is indeed Charles who narrates the story and is also the protagonist, but his sacred and profane memories as recounted in this book are all memories of his friendship and involvement with the wealthy, aristocratic, and Roman Catholic Flyte family, owners of the palatial country estate called Brideshead Castle in Wiltshire. The action of the novel covers the period from about 1923 through much of the Second World War. Charles first becomes acquainted with the family’s profligate son Sebastian while both are students at Oxford, and comes ultimately to know his unconventional sister Julia, his staunch Catholic mother Lady Marchmain, and the family’s decadent father Lord Marchmain, who lives in Venice with Cara, his longtime mistress.

Waugh, who had converted to Catholicism in 1930, wrote that his aim in Brideshead Revisited was to demonstrate “the operation of divine grace” in the lives of the characters, which he defines as “the unmerited and unilateral act of love by which God continually calls souls to Himself.” Lord Marchmain openly flaunts the Church he had converted to upon marrying Lady Marchmain. Sebastian seems averse to his mother’s rigorous faith, and Julia is at best indifferent to it. Charles, a professed agnostic, is far more sympathetic to the attitudes of Sebastian, Julia, and even Lord Marchmain than to their mother or their strictly orthodox brother, the Earl of Brideshead (“Bridey”), and we see through his eyes just what this “operation of grace” leads to in each case.

The novel opens with a prologue in which Charles, now Captain Ryder, is billeted with his battalion at a country estate called Brideshead in about 1943 or 1944, and this “revisitation” prompts the memories that make up the bulk of the novel. In the book’s first section, Charles recalls his first year at Oxford, where he met Sebastian, whose partying and dissolute lifestyle leads Charles away from his well-intentioned serious studies. Charles is more interested in pursuing his interest in art than his Oxford courses, and Sebastian’s disregard for studying helps free Charles from the conventional values of his life. Sebastian takes Charles to Brideshead, but is reluctant to introduce him to the family, saying “Mummy is popularly believed to be a saint and Papa is excommunicated—and I wouldn’t know which of them was happy. Anyway, however you look at it, happiness doesn’t seem to have much to do with it, and that’s all I want.” Charles meets “Mummy” and Julia, as well as Bridey and their young sister Cordelia, and notices, to his surprise, that much of their conversation is taken up by talk of religion. Sebastian also takes him to Venice to meet Lord Marchmain.

In the second section of the novel, Sebastian’s heavy drinking, begun as a kind of escape from his parents, has turned into something uncontrollable, and he and Charles begin to quarrel about it. Still, Charles continually defends Sebastian to his mother, and ultimately falls out with her over it. After one argument she lets Charles know he is no longer welcome at Brideshead, and so he leaves, thinking never to return. An alcoholic Sebastian becomes estranged from his family and for two years is somewhere in Morocco destroying his health through drink.

Meanwhile Julia marries Rex Mottram, a wealthy Canadian businessman, to her mother’s dismay, since it turns out Rex is divorced and therefore the Catholic church will not recognize the marriage as blessed. But when Lady Marchmain’s health becomes dire, Julia asks Charles to go to Morocco to find Sebastian, so he can reconcile with his mother before his death. When Charles tracks him down in a Tunisian monastery, Sebastian has become an under-porter and is living with a wounded German deserter. Charles determines that Sebastian’s ill health will not allow him to travel.

Returning to London, Charles finds that Bridey is planning to sell the Flytes’ London dwelling, Marchmain House, and the Earl commissions Charles to paint the house in its setting before it is demolished. These paintings become so successful that Charles receives many more commissions for paintings of old aristocratic houses that are now being sold or demolished as their upkeep becomes more difficult in the modern world. In the third section of the book Charles, now married (unhappily) with two children, is a very successful architectural painter. He reconnects with Julia (now separated from Rex) on an ocean voyage, and the two become intimate and plan to divorce their spouses and marry each other. Meanwhile Cordelia, returned to England after volunteering as a nurse in the Spanish Civil War, brings news of Sebastian: his health steadily declining, he will very likely die soon in his Tunisian monastery. And ultimately, Lord Marchmain returns to Brideshead, coming back to England on the eve of the war. Having quarreled with Bridey over his eldest son’s marriage to a woman past childbearing age, Lord Marchmain makes Julia heir to his estate.

That’s all you get out of me, since anything more I say will certainly be a spoiler.

Charles himself remains a scoffer at religion throughout all of this, and is particularly hostile toward Catholicism as the novel draws toward its conclusion. Some of Waugh’s critics, like Edmund Wilson above, apparently felt the same way. On the other hand, Chaim Potok, the conservative rabbi-turned best-selling author of The Chosen and other novels, said that reading Brideshead Revisited at he age of 16 was what made him want to be a writer. Taking faith seriously, taking the concept of Grace seriously, Waugh wrote in a letter to his friend Lady Mary Lygon (believed by some to be the real-life model for Julia in the novel), is what the novel is all about:

I believe that everyone in his (or her) life has the moment when he is open to Divine Grace. It’s there, of course, for the asking all the time, but human lives are so planned that usually there’s a particular time—sometimes…on his deathbed—when all resistance is down and grace can come flooding in.

A reader can see this moment coming upon all the Flyte family one way or another. As for the narrator, his final reaction to all this comes in the novel’s epilogue, when, having returned to the manor house during the war many years after his final contact with the Flyte family, he reflects upon all that has happened.

One other matter of some debate among readers and critics of the book is the relationship between Charles and Sebastian. One view is that the Sebastian/Charles connection is in the Victorian tradition of intimate male friendships exemplified by, say, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, or described by Tennyson in his elegy on Arthur Henry Hallam:

I hold it true, whate’er befall;

I feel it, when I sorrow most;

’Tis better to have loved and lost

Than never to have loved at all.

Others have seen this kind of interpretation as a more or less desperate attempt to keep great works of twentieth century literature strictly in the heterosexual camp. Waugh does not go so far as describe any physical intimacy between the two, but he makes it clear that Charles’ attraction to Julia is based largely on her physical resemblance to her brother. Lord Marchmain’s mistress recognizes the relationship between the two young men when they visit Venice, though she interprets it as part of his emotional development. Sebastian goes on to what is certainly a new lover in Morocco where he lives with his wounded German. And in the book’s third section, Julia says to Charles “You loved him, didn’t you?” and Charles says “Oh yes. He was the forerunner.”

But most significant is probably Charles’ observation about his first summer spent with Sebastian, of which he reminisces:

Now, that summer term with Sebastian, it seemed as though I was being given a brief spell of what I had never known, a happy childhood, and though its toys were silk shirts and liqueurs and cigars and its naughtiness high in the catalogue of grave sins, there was something of nursery freshness about us that fell little short of the joy of innocence.

Nothing else they do could possibly be counted as “high in the catalogue of grave sins,” but homosexuality would certainly have been considered so by the Catholic church in the 1920s. It would surely have been thought an obstacle between Sebastian—or Charles—and the opportunity of Grace they might be offered. In short, to deny Charles and Sebastian’s sexuality seems a kind of special pleading in which, as Christopher Hitchens wrote in 2008, “the ridiculous word ‘platonic’…for some peculiar reason still crops up in discussion of the story.” I think we can safely call Brideshead Revisited the first acclaimed English novel featuring openly gay protagonists.

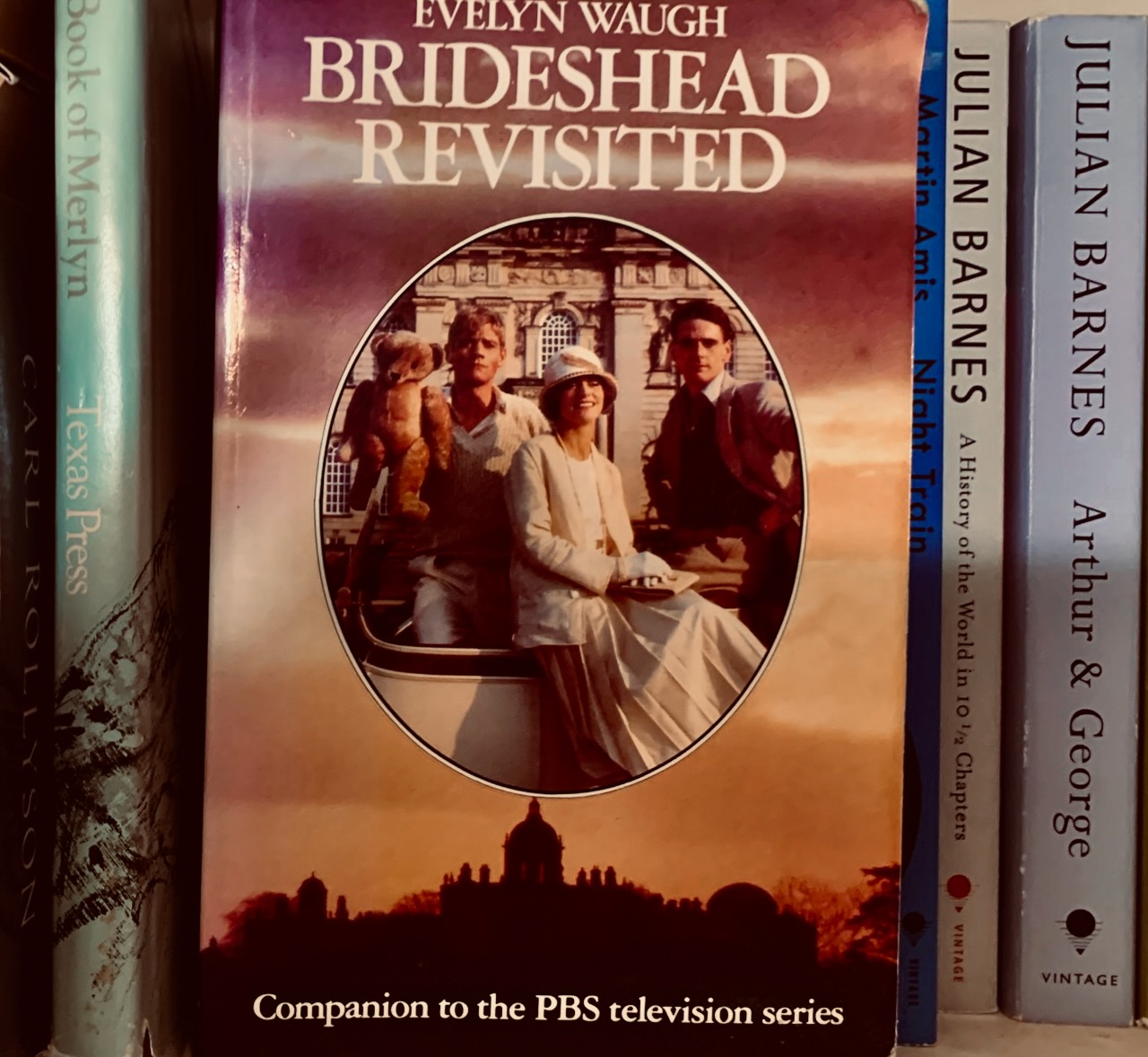

There is a decent 2008 film version of the novel directed by Julian Jarrold and featuring Emma Thompson in an acclaimed performance as Lady Marchmain. But nothing can touch the magnificent 11-episode television serial from 1981, which starred Jeremy Irons as Charles and Anthony Andrews as Sebastian. This is an incredibly faithful adaptation, but don’t let it substitute for actually reading the novel. Watch it afterwards.