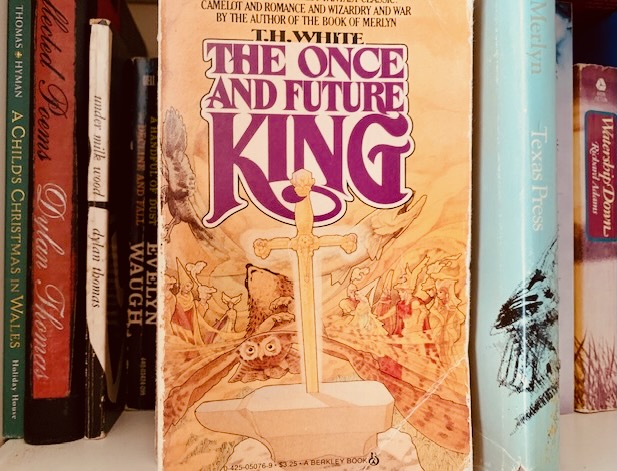

Probably the most popular twentieth century treatment of the King Arthur story, and the one that does least to eviscerate the traditional Arthurian legend, is T.H. White’s four-part novel The Once and Future King, published as a complete compilation in 1958 after its original parts (The Sword in the Stone, The Queen of Air and Darkness, The Ill-Made Knight, and The Candle in the Wind) had been published separately between 1938 and 1940. The complete book is perfectly coherent, by the way, and you really feel the story is incomplete if you haven’t read all the parts to it.

White would have become familiar in his youth with Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s Idylls of the King, the most complete and popular treatment of Arthurian legend in the nineteenth century–twelve separate and separately published books of blank verse a la Milton (who originally planned his own English epic to be about King Arthur, not “man’s first disobedience”), thus forming a kind of Tennysonian epic whole of King Arthur’s reign. But White’s chief source for his novel is Sir Thomas Malory’s long prose romance Le Morte Darthur, completed in around 1470 and printed by William Caxton, first printer in England, in 1485, the same year Henry Tudor defeated Richard III to become Henry VII, first Tudor king of England. At the end of his work, Malory mentions how “some men say” that King Arthur did not die but was borne to the Isle of Avalon, the fairy isle of the Lady of the Lake and there he would stay, while his wounds were healed, until the time in the future when Britain needed him most. Thus he was known as Rex quondam, rexque futuris—that is, the Once and Future King. Caxton dedicated the book to Henry, who being of Welsh heritage, identified with the Celtic King Arthur. It was great Tudor propaganda to suggest that in the return of a king of Celtic heritage, Arthur was making his return. Henry even named his eldest son and heir Arthur, just in case anybody missed the point.

White’s Book One, The Sword in the Stone, tells the story of the young Arthur’s fostering by Sir Ector and tutoring by the wizard and seer Merlyn, and it has tended to be the most popular part of White’s story, But let me just say at the outset that I have never been a big fan of the Disneyfied version of The Sword in the Stone—some of it was just plain silly, particularly the things added to the plot that are not in the novel—Kay’s getting a second squire named Hobbs, for instance, or the squirrel who falls in love with the transformed Arthur. But the silliest of all is Merlyn’s “wizard’s duel” with the witch “Madam Mim,” which is not simply ridiculous in itself, but does nothing to forward the plot of Arthur’s youth. I guess what I’m saying here is, read the book and don’t watch that travesty of an animated movie.

I did rather like the film version of Lerner and Loewe’s musical Camelot, though which is based on the third and fourth books—The Ill-Made Knight, the story of Lancelot’s youth, his gaining his reputation as Arthur’s greatest knight, his love affair with Queen Guinevere, and his failure in the Quest of the Holy Grail; The Candle in the Wind completes the disastrous story of the love triangle that leads to the tragedy of Arthur’s doom and the fall of the Round Table—brought about largely by the king’s nephew Agravaine and his bastard son Mordred. Camelot skips the Holy Grail story and focuses on the building of the Round Table and the catastrophic love affair. And it does so pretty well. If you are reading this review, you may already be familiar with my own “Merlin Mysteries” series, and I can trace my interest in the Arthurian legend directly to my viewing of this film on a high school field trip in 1968, after which I was inspired to read White’s entire novel—more than 600 pages worth. And the rest is history.

I should mention that the second book of the novel, The Queen of Air and Darkness, fits nicely into White’s overall plan, which is particularly concerned with the childhood “making” of the novel’s heroes—Arthur in Book One and Lancelot in Book Three, and sandwiched between them, Book Two relates the childhood of Arthur’s nephews from the kingdom of Orkney, Gawain, Gareth, Gaheris, and Agravaine, and of their mother, Arthur’s half-sister Morgause who, at the end of Book Two, seduces her young half-brother and is impregnated with the ultimate villain of the book: Mordred.

One of the surprising parts of the book is the narrative voice. It is the voice of an omniscient contemporary twentieth-century storyteller who knows he is speaking to a twentieth-century audience, and not, as might be more common is this genre, a narrator who speaks as if he’s a part of the medieval world he describes, though he speaks in modern English. Part of what makes this narration successful is White’s unique take on the character of Merlyn. Merlyn, we are told, lives backwards. As the story goes on, he grows younger while everyone else grows older. And Merlyn lived his youth in the twentieth century. In a sense, then, the narrative voice of the novel is parallel with Merlyn in this way. When the narrator talks about Sigmund Freud or Adolph Hitler and applies his experiences to Arthur’s time, it can feel a little strange, but hey, if Merlyn can make use of this knowledge, why can’t the narrator? Secondly, the narrator assures us that his characters are real, and speaks about actual historical figures as legendary—whether they are William the Conqueror who won the fictional Battle of Hastings or the historical Robin Wood (whose name some have misremembered as Hood) who befriends Arthur as a lad.

White uses his narrative skills as well to connect the separate parts of his novel thematically in several ways: the Lancelot-Guinevere love story that Camelot picks up on is one connection. Another is the role of the Orkney tribe, particularly Mordred but the others as well, most importantly Gawain, whose clannish devotion to his family causes major problems to the survival of Arthur’s Round Table. And third, and ultimately most important, is Arthur’s devotion to civilizing his country. This dream begins in Merlyn’s education of him in his childhood, when he (and the narrator) call him by the nickname “Wart” ;

“If I were to be made a knight,” said the Wart, staring dreamily into the fire, “I should insist on doing my vigil by myself, as Hob does with his hawks, and I should pray to God to let me encounter all the evil in the world in my own person, so that if I conquered there would be none left, and, if I were defeated, I would be the one to suffer for it.”

It is this initial spark that Merlyn sees in his pupil that he decides to educate through teaching the boy about how the natural world works, and the way various creatures govern themselves in nature. Memories of these lessons inspire Arthur in developing, through his program of channeling the violent instincts of knights, the revolutionary concept of chivalry, of using might for right. Ultimately he tries to reform the ideal of chivalry into one of truly just society, one which he doesn’t quite reach by the end of the novel—a failure that he feels makes his life an exercise in futility in the end. Indeed if I tell the very ending of the novel it’s not so much a spoiler as a hint of how Arthur the rex quondam might yet, despite all hope, become rex futuris. In his tent before the final battle of his life, Arthur, like Christ in Gethsemane, is tormented by what seems the failure of his dream of a just society. He contemplates might winning in the end because men are incapable of reform, and evil must win. In another train of thought, he wonders if good and evil actually exist at all, and whether human beings are simply the pawns of indifferent natural forces. But finally, Arthur calls a young page boy, whose name is Tom of Warwick (i.e. Thomas Malory), and convinces the boy to stay out of the battle and live on to tell the story of the Round Table to others—Arthur will indeed live again in his story, as Malory passed it down to Tennyson and he to White… and White to me, for that matter. The world would not forget Arthur nor would it let die the dream of a just society: “The fate of this man or that man,” Arthur decides in the end, “was less than a drop, although it was a sparkling one, in the great blue motion of the sunlit sea.” The sparkle Malory passed on is surely that great ideal of Arthur’s.

And that of course is the legend White is playing on with the title of his work. Like Malory’s it’s a compilation of related books written separately—for Malory, it was eight different books; for White it was four. For Caxton, the legend of Arthur’s return can be applied to the advent of the Tudor monarchy; for White, it may be that at the end of his novel, when he gives us a long discussion of the various warring thoughts Arthur struggles with as he worries his career has been a failure, the final return of Arthur, drawing from the imagery with the Second Coming of Christ, may be in White’s own time: recall he writes this last book in 1940, during Britain’s darkest hour. What better time for the return of Arthur—when the king may complete his task and create a truly just society after defeating the dark forces of Nazis who believe raw power is the only criterion for government. It may be that this is what makes White’s novel as relevant today as it was in 1940.

The Once and Future King does not appear on most of the best-known “Greatest Books” lists, though it does do well on lists of some of the best genre novels: on Fantasy Book Review’s 2022 list of the “Top 100 Fantasy Books,” White’s novel comes in at number 22, and on NPR’s 2011 Readers’ Survey of some 60,000 readers, The Once and Future King ranked number 47 among the “Top 100 Science-Fiction/Fantasy Books.” In the British periodical Modern Fantasy in 1988, White’s book was included in the unnumbered “100 Best Novels” in the genre, and Time magazine listed it in its own 2020 list of the “100 Best Fantasy Books of All Time,” as compiled by a committee of some of the major authors in the genre. As for compilations considering it beyond the narrowness of its genre, the Library Journal in 1999 ranked it as number 100 among its 150 “Books of the Century,” and in 2021 the Center for Fiction included it as one of its “200 Books That Shaped 200 Years of Literature.” The book came in at number 64 on the 1999 Bookman.com survey of the “100 Favorite Novels of Librarians,” and it appears on the admittedly subjective list compiled in 1984 by author and longtime reviewer of novels Anthony Burgess (whose A Clockwork Orange is also on my list) called “Ninety-Nine Novels: The Best in English since 1939). And finally, The Once and Future King is included in Parade Magazine’s 2016 list of “The Best Books of the Past 75 Years.” And of course, I’m including it here as number 96 (alphabetically) on my own list of “The 100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”