Riga is the capital of the Baltic nation of Latvia. With a population of 625,000, it is the size of Memphis. But it’s a special place unlike any you’ve ever been before.

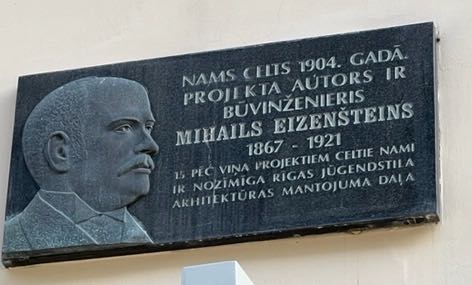

In the first place, the city boasts some 800 buildings in the Art Nouveau (or as the Germans called it, Jugendstil) style of the early 20th century—that’s more than any other city in Europe. On the street called Alberta iela, building after building displays a colorful, flamboyantly decorated exterior with mythical beasts, flora, masks and demons. The genius behind this street, Riga’s most famous architect, was Mikhail Eisenstein. Between 1901 and 1906, he was responsible for the building pictured at the beginning of this post, and dozens more like it.

Mikhail Eisenstein was also responsible for a son, Sergei, born in Riga in 1898. At that time, Latvia and its neighbor Estonia were known as Livonia, a part of the Russian Empire, and when he was 20 Sergei dropped out of architecture school and joined the Red Army to participate in the Russian Revolution. He went on to become one of the most important directors, film editors, and film theorists of the early cinema, creating among other films Battleship Potemkin (1925), still considered one of the greatest films of all time.

If this much gives you the impression that Latvians place a high value on the arts, you would not be wrong. A list of famous Latvians you might have heard of might begin with world famous dancer Mikhail Baryshnikov. Several Latvian Americans have had successful acting careers—Peggy Lipton (best known for The Mod Squad and Twin Peaks, as well as her marriage to Quincy Jones), and her daughter Rashida Jones (of TV’s Boston Public, The Office, and Parks and Recreation), and perhaps most famously, Buddy Ebsen, who began as a song and dance man in films but hit it big as Jed Clampett on The Beverly Hillbillies. But of course, the biggest Latvian American name in the arts is Mark Rothko, one of the best known abstract expressionists, famous for his color field paintings.

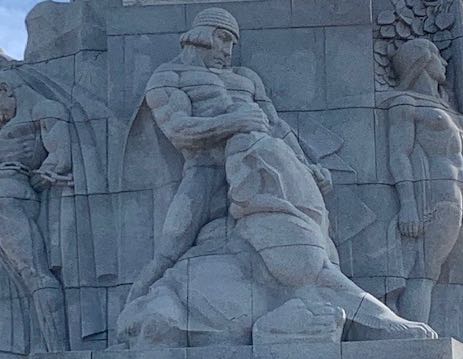

Walk down Brīvības bulvāris toward Riga’s medieval Old Town (recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage site) and you’ll pass the magnificent manifestation of Riga’s devotion to the arts, this one a monumental sculpture, the Freedom Monument, known as “Milda” to locals. This monument, paid for by public donations, was erected in 1935 on the spot where a monument to Russian czar Peter the Great once stood. It celebrates Latvia’s independence from Russia after the First World War. The sculptor, Kārlis Zāle (1888-1942) had studied in Russia and in Germany, but returned to Riga in 1923, where he taught sculpture and created several monumental works of art, the Freedom Monument being his masterpiece.

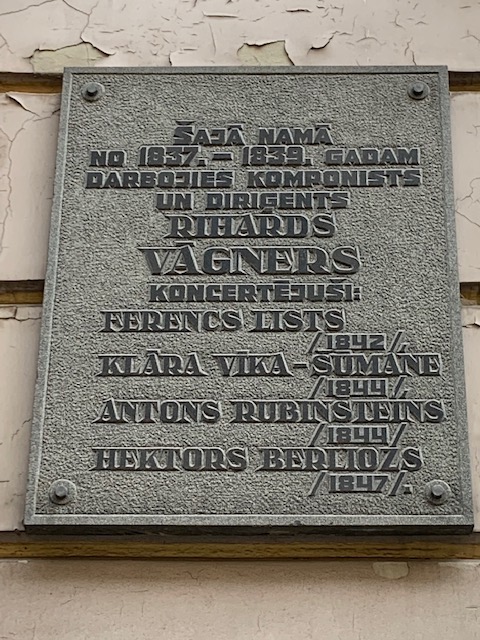

Old Riga dates back to 1201, when it was founded by German Teutonic knights, intent on Christianizing the local people, and, of course, annexing the territory. Sweden took possession of the city in 1621. But Russia gained control of the city in 1710, and Latvia became a part of the Russian empire for more than 200 years. The Old Town reflects all of this history, and reflects, as well, the Latvian reverence for the arts: In particular, music shines in the Old Town, where the opera house (which also houses the ballet that gave Barishnykov his start) boasts a history that includes Richard Wagner: Wagner moved from Königsberg to Riga in June 1837, where he became musical director of the Riga Opera House. By 1839 Wagner and his wife Minna, having accumulated huge debts in Riga, were forced to flee the city to escape their creditors, making a stormy sea passage to London. In a way it turned out well for Wagner: Though he was plagued by massive debts the rest of his life, the sea voyage inspired him to write one of his first successful operas, The Flying Dutchman.

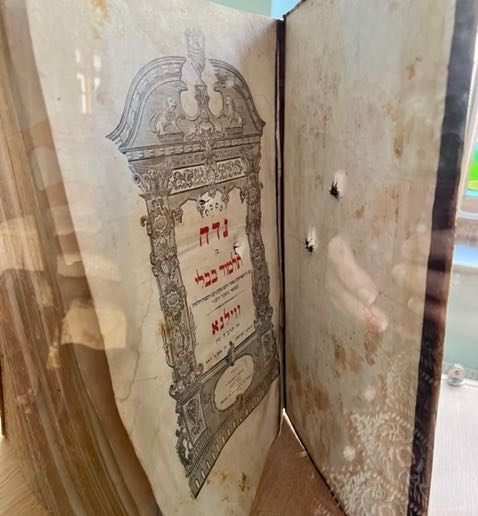

It’s good to note that the Art Nouveau architecture Riga is famous for appears in parts of Old Town as well. A significant building here a little off the beaten path is Riga Synagogue, a beautiful Art Nouveau structure built in 1905. Prior to World War II, there were 100,000 Jews in Latvia. There were 5,000 left at the end of the war. Before the death camps were developed in Poland, Nazis took groups of Jews into the forests about Riga and shot them by the thousands. Germans burned down every other synagogue in Riga, but left this one standing because it was too close to other buildings that they didn’t want to harm. And so it survived the Holocaust, though it was damaged by neo-Nazi bombs in the 1990s. The synagogue was fully restored in 2009 and worth visiting. One of the remarkable displays in the synagogue is a Babylonian Talmud, marked with blood stains and bullet holes, found near Riga. No one knows what happened to its original owner.

So—if the Latvians are such strong supporters of the arts, what about literature, I can hear you asking. Isn’t this blog called “The Rambling Writer”? Well, the writers get their share of love in Riga as well. Though Latvian culture had been dominated by Germans, Swedes, and Russians for centuries, Latvians have a long history of folk songs, which to this day are celebrated in national festivals. A strong national movement beginning in the 19th century included poets like Andrejs Pumpurs, who published the epic poem Lāčplēsis (“The Bear-Slayer”). Nationalist movements were springing up throughout Europe in the 19th century, and a popular assumption at the time was that to be a true nation, a people must have a national epic, and that is what Pumpurs succeeded in creating with Lāčplēsis. Based on old folktales (like the Finnish Kalevela published earlier in the century), Lāčplēsis tells the story of a mythic hero who battles the Germans at the time of the Teutonic knights. Born with the ears of a bear, he gets his bear-like strength from his ears and when, like Samson, his ears are cut off, he can finally be defeated. A decent English translation of the epic (by Arthur Cropley) is finally available (published in 2021) entitled Bearslayer: A Free Translation from the Unrhymed Latvian into English Heroic Verse. The story is an important part of Latvian culture, and scenes from the epic are sculpted on a panel of the Freedom Monument.

Other writers specifically honored in Riga include the poet Aleksandrs Caks, a modernist poet who wrote about everyday life in Riga during its independent period after the First World War. When the Soviets annexed Latvia, Caks was accused of “politically incorrect poetry”, and he died shortly thereafter. There is now a new museum honoring him in the flat that he lived in from 1937 until his death in 1950. There’s also a granite statue of realist author Rudolfs Blaumanis (1863-1908) not far from the Freedom Monument in a beautiful green park that separates Old Riga from the city center. Blaumanis was a satirical journalist, a poet, fiction writer, and successful playwright, who wrote in both German and Latvian. He created a number of vivid characters who today are classic figures in Latvian literature.

Perhaps the most significant writer in Latvian literature is Jānis Pliekšāns (1865-1929), better known by his pen name Rainis. He has a major street named for him—the street that runs along that major central park in the city. Rainis was a poet, translator, politician and playwright. His best-known play, Uguns un nakts (Fire and Night) was written in response to the failed revolution of 1905. It is a dramatized version of the story of the epic Bearslayer, in which the colonizing German forces of the epic are equated with the domineering Russian imperial forces. Rainis advocated for an independent Latvian state, a dream he saw realized in 1918 when the country declared its independence. After the post-WWII Soviet annexation, Uguns un nakts was often performed, with the Latvian audiences understanding that the Germans in the play were stand-ins for the Soviets. When a rock-opera version of the story premiered in 1988, it helped spark the wave of national feeling that led to Latvia’s ultimate independence in 1991.