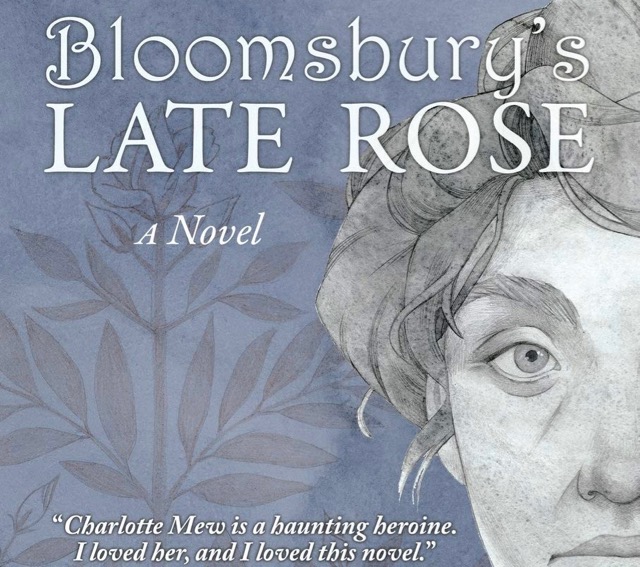

Bloomsbury’s Late Rose

Pen Pearson (2019)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

If you’ve never heard of the Edwardian British poet Charlotte Mew, you’re not alone. Mew is these days as little known as she was during most of her life. In Bloomsbury’s Late Rose—her fictionalized story of Mew’s life— author Pen Pearson laments that Mew’s poetry “remains underappreciated today,” and expresses her hope that her novel “leads readers to Mew’s poems and fulfills Thomas Hardy’s prophecy that Charlotte Mew’s poems will be read when other poets’ work is forgotten.”

So clueless was I about Mew’s career that I thought when I picked up this book, that I was going to be reading an imagined account of some incident in Virginia Woolf’s life, since she’s the woman I most associated with Bloomsbury. Imagine my surprise when I met Charlotte Mew—whom Woolf herself called “very good and interesting and unlike anyone else.” The book opens with a prologue dated 1894, providing an account of the pact Charlotte makes with her sister Anne: Having seen both their brother Henry and their sister Freda institutionalized in asylums for the insane, the two sisters vow never to marry, since marriage is likely to result in children, and neither wishes to pass on the family curse to their offspring.

The first chapter begins fifteen years later: Charlotte and Anne have remained close, and have remained faithful to their vow never to marry, so at this point they are nearing forty and living with their ailing mother and her long-term maid in a house in the Bloomsbury section of London. Because their architect father Frederick Mew had died in 1898 and left the family in financial difficulties, they have been forced into the demoralizing step of taking in a tenant for their top floor. As the novel goes on and the family descends further and further into what at the time was called “genteel poverty,” more and more of the family home gets let out to boarders.

Those fifteen years since the Prologue have been discouraging in other areas as well. The aspiring writer Charlotte, who in 1894 had had a story published in The Yellow Book, had followed that up with only a few more stories five years later, but no great success. And Anne, who had had similar brief success with a painting early on, had nothing subsequently to show for it. Charlotte muses over her disappointments early on in the book—“Her run as a fiction writer and essayist….That utter foolishness in Paris, not so long ago….It seemed now as if she were waiting, but for what?” (The “foolishness in Paris,” we gradually piece together, alludes to Charlotte’s relationship with Ella D’Arcy, the assistant editor of The Yellow Book, to whom Charlotte was strongly attracted and whom she followed to Paris in 1902, only to be soundly rejected). We soon realize that while Charlotte’s own preferences make her vow never to marry and have children less than onerous for herself, it is apparently far more difficult for Anne, who seems clearly attracted to a gentleman at their church—but never acts on that attraction because of her vow and her fear of the “family curse.”

We get a brief episode of Charlotte and Anne visiting their sister Freda in the asylum, a grim scene that underscores the necessary permanence of Freda’s confinement. Things take an optimistic turn when the sisters inherit a small stipend from a deceased relative—it amounts to little but is enough to rent for Anne a studio in which she can paint. Unfortunately, financial straits compel her to take a menial job that tires her out and leaves her little time for her art. The studio, however, becomes a kind of refuge for the sisters when their own home shrinks to only a few rooms surrounded by tenants.

Charlotte does finally begin to achieve some success in her writing, mainly through her poetry, which she turns to as her personal life begins its gradual decline. Her poems reflect the social and political concerns of her time as she begins to take part in a London salon convened by Mrs. Dawson Scott, a hostess with the provocative nickname of “Sapho.” Here she reads aloud her first important poem, “The Farmer’s Bride,” which had been published in The Nation in 1912 and thus drew Mrs. Scott’s attention. The poem, a dramatic monologue in the Victorian manner of Robert Browning, depicts a troubled marriage from the husband’s point of view and with a keen psychological insight. I should note that an appendix to the novel includes six more of Charlotte Mew’s poems that provide evidence of her skill as a first-rate modern poet.

It is in this salon that Charlotte meets May Sinclair, a popular novelist, critic, and suffragette whose views certainly influenced Charlotte’s. Charlotte becomes a kind of protégé of Sinclair’s for a time, but as Pearson makes clear, her interest in Sinclair is not solely literary, and when Charlotte apparently misinterprets Sinclair’s attitude, it leads to a mortifying scene in Sinclair’s bedroom. It is about the last we see of Charlotte’s endeavors at true intimacy, except with her sister Anne.

Charlotte’s lesbianism is acknowledged by her biographers, though Pearson is quite restrained in its presentation (as Charlotte was herself). She describes Charlotte’s clothing in the style of her times: “Gone were the full skirts and crinolines, fitted bodice, and stiff, upright collar of the Victorian era. Today the fashionable Edwardian woman wore the less confining shirtwaist and a more fitted, ankle-length skirt, which was slightly less cumbersome than its predecessor.” But she stops short of depicting Charlotte’s attire as some of her biographers describe: “She was a tiny woman with short hair who wore tailored men’s suits and always carried a black umbrella,” says the Poetry Foundation web site. Perhaps Pearson thought such a description would be too stereotypical for the highly individualistic Charlotte she is creating in her novel.

But though personally distressing, Charlotte’s involvement in the salon ultimately leads to the publication of her first collection of poems, The Farmer’s Bride, in 1916, and although it fails to sell out the first printing, it does raise her visibility and when an American publisher picks it up and issues an expanded version under the title Saturday Market, she at last attains some recognition, even meeting Thomas Hardy, who champions her work. Still, her economic means continue to dwindle, so that in 1923, through the efforts of Hardy, Sydney Cockerell, John Masefield and Walter de la Mare, she receives an annual Civil List pension of £75, which keeps her and her sister from destitution.

I don’t want to fill this review with spoilers, but you can probably guess that the story ends tragically. As a fictionalized biography, it is difficult to give such a story a narrative arc, but Pearson manages to structure the book around two opposing forces: on the one hand Charlotte’s personal and social life, a trajectory complicated by her vow of marital celibacy, her economic circumstances, and her sexuality; and on the other hand her professional life, her craving for literary recognition and notoriety. As the novel progresses, the first of these arcs slides steadily downward, while the second gradually rises to undeniable success.

Pearson has obviously meticulously researched not only Charlotte’s life but the social and physical details of Edwardian London, including the position of British women in the age of first-wave feminism, so that a reader feels comfortably at home in Charlotte’s Bloomsbury. Those details construct a life story in which, to be honest, not a whole lot happens. But what Pearson contributes from her own imagination is the rich interior life she attributes to Charlotte—an interior life that can be inferred to a large extent from Mew’s surviving poems.

This is a book that, like the woman who is its subject, deserves more attention than it has been getting. Gracefully written, emotionally understated but powerful, this is a book that you will think of often long after you leave it. Four Shakespeares for this one.

NOW AVAILABLE:

To the Great Deep, the sixth and final novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at http://encirclepub.com/product/to-the-great-deep/

You can also order from Amazon (a Kindle edition is available) at https://www.amazon.com/Jay-Ruud/e/B001JS9L1Q?ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_1&qid=1594229242&sr=8-1

Here’s what the book is about:

When Sir Agravain leads a dozen knights to arrest Lancelot in the queen’s chamber, he kills them all in his own defense-all except the villainous Mordred, who pushes the king to make war on the escaped Lancelot, and to burn the queen for treason. On the morning of the queen’s execution, Lancelot leads an army of his supporters to scatter King Arthur’s knights and rescue Guinevere from the flames, leaving several of Arthur’s knights dead in their wake, including Sir Gawain’s favorite brother Gareth. Gawain, chief of what is left of the Round Table knights, insists that the king besiege Lancelot and Guinevere at the castle of Joyous Gard, goading Lancelot to come and fight him in single combat.

However, Merlin, examining the bodies on the battlefield, realizes that Gareth and three other knights were killed not by Lancelot’s mounted army but by someone on the ground who attacked them from behind during the melee. Once again it is up to Merlin and Gildas to find the real killer of Sir Gareth before Arthur’s reign is brought down completely by the warring knights, and by the machinations of Mordred, who has been left behind to rule in the king’s stead.