The Maltese Falcon is a novel that is probably less well known than the film that was made from it—something, I suppose, like Gone With the Wind or The Godfather. In all these cases one could say that the book inspired the film, and the film still sends inspired viewers back to the book. The 1941 film noir classic (actually the third movie based on the book, but the only one people still care about) starred Humphrey Bogart in one of his most memorable roles as private detective Sam Spade, with a powerful supporting cast of Sydney Greenstreet, Peter Lorre, and Mary Astor. The continuing significance of the film has helped buoy Dashiell Hammett’s reputation, and keep him from being dismissed as “merely” a genre writer of the “hard boiled” detective variety.

If you haven’t noticed, my list of top novels makes no distinction between “literary” novels and “genre” fiction. A great novel can fall into the category of “romance” (Pride and Prejudice?), “science fiction” (Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy?), “war” (The Red Badge of Courage?), “fantasy” (Watership Down?) or in this case “detective/mystery” (of which I’ve already put several on my list: The Woman in White, The Hound of the Baskervilles, Murder on the Orient Express, The Big Sleep) and am now adding another. Hammett is for many the father of the “hard-boiled” detective, and Sam Spade is his prototype. “Hard-boiled” is, I suppose, metaphorically like the egg—with a hard shell on the outside and a hard yolk on the inside—as opposed to a mushy poached egg, say. No mushiness in the unsentimental, cynical hard-boiled detective, who fights crime and often a corrupt justice system as well, solving crime with his wits and, usually, a bottle of booze on the side. Raymond Chandler’s Philip Marlowe is the heir of Hammett’s prototypical Sam Spade (and Bogey immortalized Marlowe on screen as well).

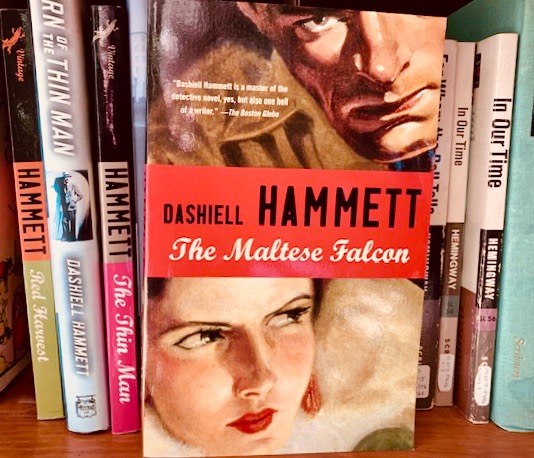

Hammett’s influence on detective fiction has been recognized and celebrated in significant ways: In 1990, the British Crime Writers’ Association released a list of the “Top 100 Crime Novels of All Time,” and ranked The Maltese Falcon as number 10. In 1995, another group, the Mystery Writers of America, released their own “Top 100” list, and ranked The Maltese Falcon number 2. But it’s not only honored as a mystery novel: The Maltese Falcon appears as number 56 on the Modern Library’s list of the best 100 English language novels of the 20th century, and on The Guardian’s list of greatest English language novels. In addition, Hammett’s novels The Thin Man (which inspired another great film)(#31), Red Harvest (#39) and The Glass Key (#88) also appear on the Mystery Writers of America list, while the Crime Writers’ Association ranked The Glass Key #31 and Red Harvest #94. And more mainstream Time Magazine included Red Harvest on its “100 Greatest Novels” list. And The Maltese Falcon comes in at #42 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

Hammett spent seven years (with time out to fight in World War I) working as an operative for the Pinkerton Detective Agency, but ultimately left the agency because of its anti-labor philosophy and its role in strike breaking. He became a champion of left-wing causes afterwards, but also applied his training as a detective to his detective fiction, along with his learned distrust of the ruling social order to bring about justice. By 1929, he was translating his experiences into fiction and in September of that year, he began serializing The Maltese Falcon in H.L. Mencken’s pulp magazine Black Mask. It was published in book form by Knopf in 1930, and his editor tried to get Hammett to tone down the sexuality of Spade—and the implied homosexuality of the perfumed and effeminate criminal Joel Cairo–both of which she thought may put readers off. But the book was ultimately published as Hammett wrote it.

If you’re not familiar with the story, it takes place in San Francisco. Hammett tells it from a third-person objective point of view—a narrative stance that prevents the reader from knowing anything about Sam Spade’s inner thoughts or emotions, and thus aids in his “hard-boiled” persona. Spade and his partner Miles Archer run a detective agency, where a woman calling herself “Miss Wonderley” hires then to follow a man named Floyd Thursby who, according to her, has run off with her sister. Archer volunteers to follow Thursby that night, he winds up shot to death. And when Thursby turns up dead, the police suspect Spade of having killed Thursby in revenge for his partner, or of having killed Archer because he was having an affair with his partner’s wife. Which he was.

Spade discovers that “Miss Wonderley” is actually a woman named Brigid O’Shaughnessy and that she’s not looking for her sister at all, but rather for a black statuette of a bird, a 400-year-old golden falcon studded with priceless jewels, which had been made by the Knights of Malta as a gift for the King of Spain, but which had been stolen by pirates before reaching the royal court. The black enamel coating disguises the bird’s enormous value, and others are searching for it in addition to Miss O’Shaughnessey. One of these was apparently Thursby. Another is the jovial but incredibly dangerous fat man, Casper Gutman, who tells Spade the history of the falcon. Another is the Levantine felon Joel Cairo.

When Spade tries to get O’Shaughnessey to open up and tell him the truth, she distracts him from the question by kissing him and spending the night in his bed, but when he wakes up next to her, he leaves her sleeping and goes off to search her apartment. When he tries to get more of the story out of Gutman, the fat man drugs him and he wakes up alone on Gutman’s hotel room floor. When he returns to his office, a wounded ship captain shoves a package into his hands and dies. The package contains a black statuette of a falcon.

What happens after that takes several twists and turns, but I won’t spoil it for you if you haven’t seen the movie or read the book. Suffice it to say that all the players do come together as they come after the incalculably valuable bird, “the stuff that dreams are made of.” And the distraction of the falcon has probably taken our eyes from the mystery this all started with: who killed Thursby—and who killed Spade’s partner, Miles.

Perhaps the most admired section of the book is Spade’s long speech near the end, which many read as a statement of the hard-boiled detective’s code:

“Listen. This isn’t a damned bit of good. You’ll never understand me, but I’ll try once more and then we’ll give it up, Listen: When a man’s partner is killed he’s supposed to do something about it. It doesn’t make any difference what you thought of him. He was your partner and you’re supposed to do something about it. Then it happens we were in the detective business. Well when one of your organization gets killed it’s bad for business to let the killer get away with it. It’s bad all around—bad for that one organization, bad for every detective everywhere. Third, I’m a detective and expecting me to run criminals down and then let them go free is like asking a dog to catch a rabbit and then let it go. It can’t be done.”

The novel was well received. Famous wit Dorothy Parker claimed to be “in a daze of love” with Sam Spade, and said she had read the novel 30 or 40 times. Curiously, Hammett never used him in another novel. But he remains one of the most memorable detectives in fiction. Raymond Chandler, in many ways the heir to Hammett’s literary legacy, wrote this of him: “He was spare, frugal, hard-boiled, but he did over and over again what only the best writers can ever do at all. He wrote scenes that seemed never to have been written before.”

If you want to see just what it is about Sam Spade that is so attractive, you really should read this novel. Then perhaps read The Thin Man. And watch a few movies.