We visited Helsinki in November because, you know, why not? We saw a remarkably low airfare advertised, and decided to see what Finland was like. We hoped maybe to get a glimpse of the Northern Lights. That didn’t pan out, since it was cloudy and snowed nearly every day. But Helsinki knows what to do with the snow, and we found that the mass transit system, particularly the ubiquitous trams, made the town easy to navigate and so easy to enjoy.

Finland isn’t a major tourist destination for Americans, but maybe it should be. Finns have been moving to the U.S since the 1640s, when a Swedish colony called “New Sweden” was formed in Delaware. John Morton, who signed the Declaration of Independence as a representative from Pennsylvania, was the great-grandson of one of the Finnish settlers of New Sweden. The largest number of Finnish immigrants moved to northern Minnesota, northern Wisconsin, and the Upper Peninsula of Michigan between 1870-1930. Perhaps the most famous Finnish-American is Eero Saarinen, the famous architect who emigrated to Michigan in 1923 at the age of 13. Most famously, he designed the Gateway Arch in St. Louis. Other Americans of Finnish descent include film stars Jessica Lange and Mat Damon, as well as director David Lynch. Jean M. Auel, author of Clan of the Cave Bear and its sequels, is a Finnish American, as are Yahoo CEO Marissa Mayer, Apple co-founder Mike Markkula, and GM CEO Mary Barra. So a lot of Finnish connections here.

Finland is a little bigger than the state of New Mexico, and has a population of 5.5 million, or about the size of Minnesota. Helsinki, the capital and largest city in the country, is roughly the size of Milwaukee, though it has some large suburbs, notably Espoo, that make the urban area seem bigger. Like many nations around the Baltic Sea, Finland has a history marked by the domination of the larger powers in the neighborhood. One of the last areas of Europe to accept Christianity, Finland was harassed by crusading armies from the German and Scandinavian states until finally becoming a part of the Swedish Empire in the late 13th century. Swedes maintained control of the country into the 18th century, when a series of wars with Russia began to threaten the territory. In 1748 the Swedish king building a great fortress on six islands in the sea off Helsinki called Suomenlinna, thought to be impregnable and colloquially known as the “Gibraltar of the North.” But when Suomenlinna fell to the Russians in 1808, it spelled the end of Swedish Finland, and the country became an autonomous Grand Duchy of the Russian Empire in 1809, remaining so until the Russian Revolution in 1917. Suomenlinna is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and is the most popular tourist attraction in Finland. You can visit it on the ferry from Helsinki, which your tram pass will get you on.

And like most countries with the kind of past that made them struggle to create and preserve a national identity, Finland honors its writers. It’s hard to go anywhere in Helsinki and not be reminded of the country’s authors and poets. But one important thing to understand about Finnish literature is that a significant amount of it is in Swedish, since a significant part of the population through the 18th century was Swedish, and a good percentage Swedish speaking people remain in the country even today. Literature in Finnish consisted mainly of oral poetry well into the 19th century. The first written Finnish was a translation of the New Testament by Lutheran bishop Mikael Agricola, accompanied by a Finnish primer called Abckiria in the 16rth century. But while establishing Finnish as a written language, the Reformation actually effectively discouraged traditional oral folk poetry because much of it was associated with pagan myths. By the 18thcentury, the oral tradition was disappearing in parts of the country, and scholars began a concerted effort to record and preserve the old songs. Preservation of these traditional poems coincided with a new desire to define Finland as a nation independent of its Russian connections. And that’s when the Kalevala was born.

In many ways, The Kalevala is the root of Finnish literature. Considered the national epic of Finland, the text was woven together by Elias Lönnrot (1802-1884), honored by a large memorial statue near central Helsinki. Lönnrot, a physician and poet fascinated by the oral traditions, who made eleven field trips around Finland and Karelia (the bordering Finnish speaking area of Russia) collecting oral poems, which he was ultimately to weave into a narrative concerning the creation of the world, subsequent conflicts between the land of Kalevala and that of Pohjola, and the story of the building and the theft of a great magical device called the Sampo, which brought its owner wealth and good fortune.

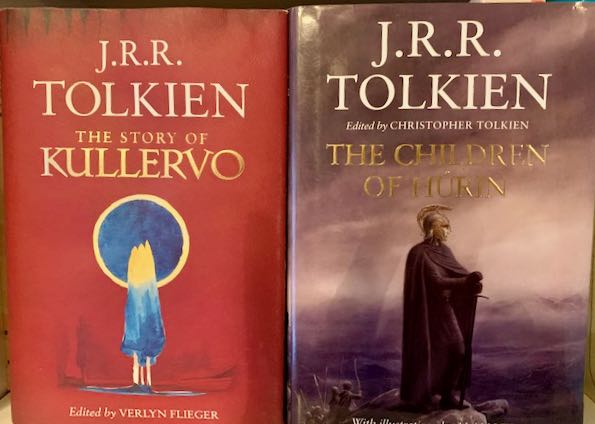

From the time of its first publication in 1835, the epic was a cornerstone of Finnish national identity and stoked the nation’s struggle for independence from Russia achieved in 1917. Its importance can be seen in its influence on later Finnish literature, as well as music—Finland’s world-renowned composer Jean Sibelius was influenced by the epic all his life, naming his first major work, Kullervo, after the Kalevala’s tragic hero. J.R.R. Tolkien was fascinated by the Kalevala in high school, and did his own translation of the Kullervo poems in his early years at Oxford, using them as an inspiration for his own tragic hero, Túrin Turambar (son of Húrin).

The significance of the Kalevala for Finnish culture is driven home when you visit Helsinki’s National Museum, and see he great ceiling frescos in the entry hall by Finnish artist Akseli Gallen-Kallela, depicting four major scenes from the Kalevala.

At the very heart of Helsinki is a long green promenade called the Esplanadi, which boasts, among other things, monuments to some of Finland’s favorite authors. Dominating the park is a tall statue in the center of the poet Johan Ludvig Runeberg (1804-1877), sculpted by the author’s son Walter. Runeberg, a Lutheran priest who produced a number of texts for the Finnish Lutheran Hymnal, wrote in Swedish, but is still considered a national poet of Finland. His best known works include Farmer Paavo, about a peasant whose faith in providence is ultimately rewarded; the epic poem King Fjalar (1844); and his magnus opus, the great epic Tales of Ensign Stål (1860), which recounts a story of the Finnish war with Russia (1808-1809) and which begins with the lyric poem “Our Land” which became the Finnish National Anthem.

Perhaps the most striking statue on the Esplanadi is that of the most famous poet in the Finnish language, Eino Leino (1878-1926), another of Finland’s National Poets, shown in a pose that looks like he is striding forward confidently. Born Armas Einar Leopold Lönnbohm, Eino published his first poem at twelve years old, and his first collection at eighteen. He was influenced by the Kalevala and included Finnish folk elements in his poetry, which remains popular in Finland to this day, most famously in his 1903 collection Helkaversiä. He was also a translator, and translated Runeberg’s Swedish verse into Finnish. He also translated Goethe and, most famously, was the first translator of Dante into Finnish. He published more than 70 books, including a journalistic account of the Finnish Civil War in 1918, which disturbed his ideals of Finnish unity.

A third memorial sculpture on the Esplanadi is dedicated to another favorite Finnish author (but again, one who wrote in Swedish), Zacharias Topelius (1818-1898). It’s a curious tribute to the writer consisting of two allegorical figures—one representing “Fact” and the other “Fable”—two aspects of Topelius works, I suppose. The sculptor, Gunnar Finne, had won a competition in 1928 held to create a memorial to the beloved author. Topelius published some five collections of poems, but it is his novels that are especially considered classics of Finnish literature, and he is deemed Finland’s “father of the historical novel.” A professor of history at the University of Helsinki who served as president of the institution from 1875-78, Topelius’s most acclaimed works are the five volumes called Tales of a Barber-Surgeon that appeared between 1853 and 1867—romanticized fiction in the manner of Sir Walter Scott concerning Finnish history during the 17th and 18th centuries. In his later years, Topelius turned to writing tales based on Finnish folklore and children’s fairy tales.

This latter aspect of Topelius is captured in a second memorial to the author. this one sitting across the street from the Design Museum in Helsinki. There was considerable backlash against the Society of Swedish Literature, which had funded the “Fact and Fable” sculpture, and a public campaign, financed by contributions from the general public, particularly from school children, resulted in this second sculpture, “Topelius as a Storyteller,” or “Topelius and the Children,” by Ville Vallgren, which graces a small park across the street from the Design Museum.

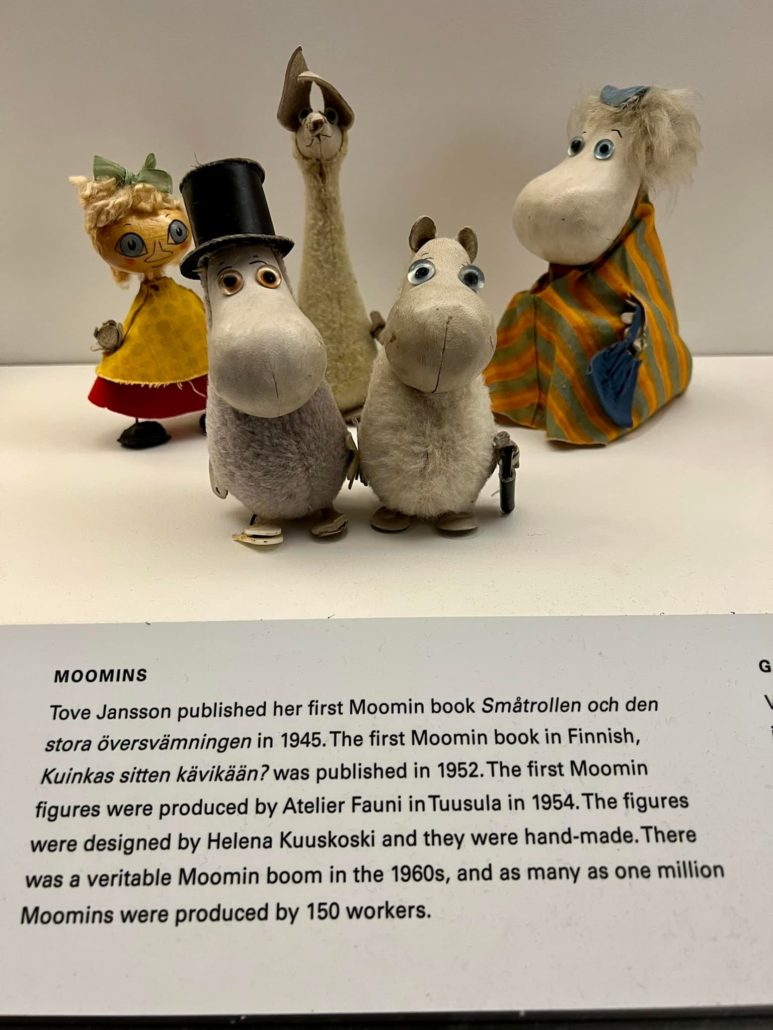

And speaking of children’s books, it would be remiss of me not to mention Finland’s most famous writer worldwide: Tove Jansson (1914-2001), creator of the Moomins, a family of roundish, white trolls who resemble hippopotamuses. She wrote her first Moomin novel, The Moomins and the Great Flood, in 1945, and wrote nine Moomin novels, five picture books, and a comic strip about the Moomins between 1945 and 1993. She received the Hans Christian Anderson Medal in 1966 for her contributions to children’s literature. He Moomin books, originally written in Swedish, were quickly translated into Finnish, and since have been translated into 4i9 languages, from Afrikaans to Welsh. There have been numerous television and film productions, video games, stage productions, musical versions and other Moomin spinoffs, including two theme parks, one in Finland and one in Japan, devoted to the Moomins. If you come to Helsinki, head downtown to the Moomin store if you want to get English translations of the books.