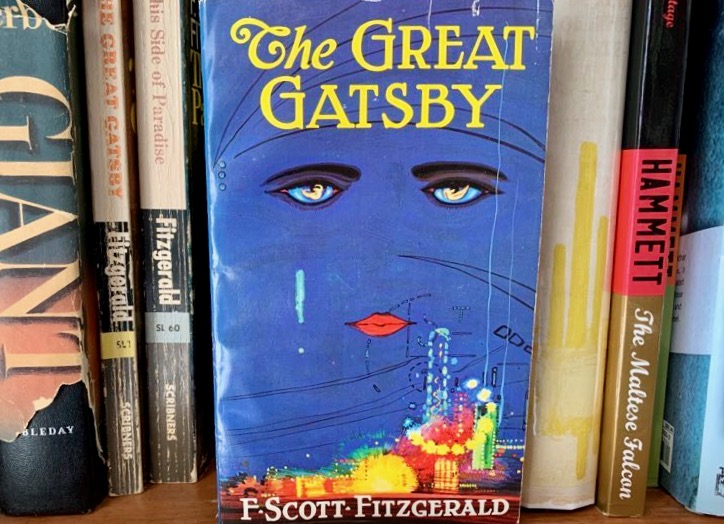

Gatsby is indeed another no-brainer for sure. It’s hard to imagine a list of the 100 best novels in English that does not include Fitzgerald’s magnum opus. As many readers will remember, it came in as number one on Time magazine’s famous list of the 100 best English-language novels since 1923 (the year Time premiered). And it was #2 on the Modern Library list of the 100 greatest English language novels, second only to James Joyce’s Ulysses. On the other side of the Atlantic, It appeared on the Guardian list of top English language novels, and on the Observer’s list of the 100 greatest world novels of all time. It came in as #3 on the Penguin list of “must read classics” as chosen by their readers. So it seems clear that just about everybody is going to concur with my inclusion of The Great Gatsby as #33 (alphabetically) on my list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

Its many adaptations are evidence of the Gatsby‘s significance in the public consciousness. The novel has been adapted as an opera, a ballet, three musicals, and several television productions. There have been four film treatments of the book, the first in 1926, just a year after its publication, though that film has unfortunately been lost. Subsequent film versions include one from 1949 starring Alan Ladd as Gatsby, one from 1974 with Robert Redford as Gatsby, and another in 2013 featuring Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby. There is even reportedly an animated version in the works.

Fitzgerald’s 1925 novel is a chronicle of America’s “Jazz Age” (a term Fitzgerald took credit for coining) and at the same time a serious critique of the “American dream” embodied in the novel by the mysterious millionaire Jay Gatsby, into whose circle the narrator, Nick Carraway, is irresistibly drawn. Oddly enough, though generally reviewed favorably upon publication, the novel was a bit disappointing in terms of sales. Its 20,000 copies sold in its first six months was disappointing compared to Fitzgerald’s previous novels, This Side of Paradise (1920) and The Beautiful and the Damned (1922). His final (non-posthumous) novel, Tender is the Night (1934), was an even greater flop sales-wise, and when Fitzgerald died in 1940 he died believing himself to be a failure. Since his death, though, readers and scholars alike have admired his novels, and the reputation of Gatsby in particular, and Fitzgerald himself, has grown astronomically.

Read today, Fitzgerald’s other novels seem dated and do not match the power and appeal of The Great Gatsby, at least in my opinion. Fitzgerald had one great novel in him, and this is it. Set on Long Island in 1922, the story begins when Yale alumnus Nick Caraway rents a house in West Egg, Long Island. A veteran of the Great War and a native of the Midwest, Nick has moved to New York to work as a bond salesman. His rental borders on the luxurious estate of the mysterious multi-millionaire Jay Gatsby.

In the neighboring village of East Egg, Nick’s distant cousin Daisy Buchanan lives with her old-money millionaire husband Tom, whom Nick knew at Yale. They have just moved here from Chicago and have a mansion of their own across the bay from Gatsby’s. From Daisy’s childhood friend Jordan Baker, Nick learns that Tom keeps a mistress named Myrtle Wilson. Several days later, Nick accompanies a drunken Tom to New York. On the way, they pass through what Fitzgerald calls a “valley of ashes”—a depressing wasteland that lies between East and West Egg (an image, perhaps, of the reality that lies beneath the glitter of contemporary society, recalling Eliot’s critical look at the modern world in his influential poem that appeared the year the novel is set). The valley becomes a significant symbol in the novel:

This is a valley of ashes—a fantastic farm where ashes grow like wheat into ridges and hills and grotesque gardens; where ashes take the forms of houses and chimneys and rising smoke and, finally, with a transcendent effort, of ash-grey men, who move dimly and already crumbling through the powdery air.

Here is the place Nick and Tom stop at George Wilson’s garage and pick up Wilson’s wife, Myrtle, and the three of them head for the city where Tom keeps an apartment for his trysts with his mistress. Several other guests arrive for a party, which breaks up when Tom breaks Myrtle’s nose after she mentions Daisy.

At one point, Nick observes his neighbor from a distance, standing outside in the dark and watching the green light of Daisy’s dock across the bay. Later, Nick receives a surprise invitation to a party at Gatsby’s estate. He attends, finds no one there he recognizes, and starts drinking heavily. Ultimately, he meets Jordan and, while talking with her, is approached by a man who introduces himself as Gatsby, and claims to have served with Nick during the war. When Nick leaves the party, Gatsby is watching him.

Nick meets Jordan again at the Plaza Hotel, where she tells him that Gatsby was in love with Daisy before the war, but that when he was deployed overseas, Daisy had married Tom. Gatsby, still obsessed with Daisy, is hoping to win her back with his new riches and his dazzling lifestyle. Eventually, he persuades Nick to set up a reunion with Daisy. The two begin an affair.

What the outcome of this affair is, and the outcome of the affair between Tom and Myrtle, I won’t tell here, nor what ultimately happens to Gatsby. Let’s just say that jealousy, unexpected violence, and nobly misplaced chivalry all play a part in the tragic turns that the novel takes. But I won’t include any spoiler here, on the off chance that you are one of the three people who has not actually read the book.

Gatsby is a realistic picture of its time. Nick, a midwesterner who attended an Ivy League school and settled in New York in time to experience hedonistic parties on Long Island, is very much a reflection of Fitzgerald himself, a Saint Paul native who attended Princeton and had a fling on Long Island with a glamorous socialite (Ginevra King), the inspiration for Daisy Buchanan. The novel’s depiction of economic prosperity, rebellious and libertine youth, wild parties and the endless supply of liquor for the well-heeled during the age of prohibition—a theme underscored by the revelation that the source of Gatsby’s great wealth is his bootlegging operations—paint a vivid picture of the “roaring twenties,” a picture Fitzgerald ultimately looks at with jaundiced eye.

Perhaps what makes Gatsby such a profoundly affecting story is its aspects of tragedy. An admirable self-made figure who rose from humble obscurity to a position of great wealth, Gatsby easily fits Aristotle’s characterization of the tragic hero as a person superior to others in some way, who falls from his high position as a result of his hamartia, literally his failure to hit the mark, usually interpreted as a “tragic flaw” or, more accurately, an “error of judgment.” Gatsby’s error is his monomaniacal quest to win back Daisy through his pursuit of the elusive “American dream.”

Thematically, The Great Gatsby is a critical and ironic revaluation of “the American dream”—the myth that in America, anybody, regardless of race, class, or economic situation, can through their own efforts attain wealth, success, a comfortable and successful life. After all, our American birthright is what the Declaration of Independence calls “the pursuit of happiness.” The American dream guarantees the success of that pursuit. In Fitzgerald’s novel, Gatsby comes from a lower class family in North Dakota, and his early romance with Daisy Buchanan, child of a wealthy family, is doomed. Despite his humble origins, Gatsby does achieve financial success—albeit by illegal means—but fails to achieve his real dream: Daisy herself. Class ultimately trumps wealth in Daisy’s choice of Tom, and Gatsby, left among the “nouveau riche” on the wrong side of the bay, can only stare longingly at the green light of Daisy’s dock across the water.

The book ends with another haunting evocation of that green light, this time coming from Nick himself—the chorus of the tragedy, or the heir of Gatsby’s obsession with the dream? He writes:

Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgiastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—tomorrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms further… And one fine morning—

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.