It seems that the reputation of Mary Ann Evans, aka George Eliot (since what Victorian publisher would accept a novel by someone with a woman’s name?), just keeps growing stronger and stronger as time goes by. Already a major novelist in her own time, with acclaimed novels like Silas Marner (1861), Daniel Deronda (1876), Adam Bede (1859), and The Mill on the Floss (1860), appreciation of her artistry has continued to escalate through the twentieth century until it seems to have reached its zenith today.

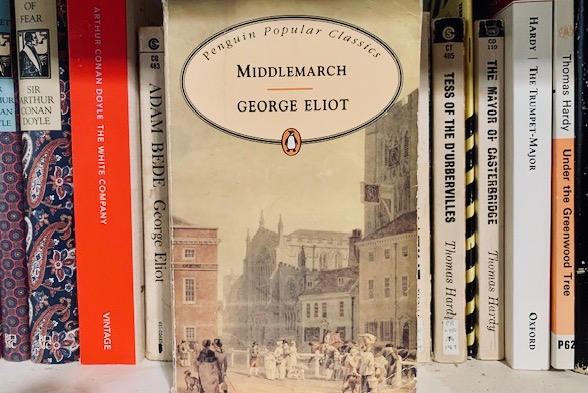

And this is especially true of a novel that debuted in 1871 to mixed reviews, but is now universally recognized as her greatest work: Middlemarch. Middlemarch ranked at number 27 in the 2003 “Big Read” sponsored by the BBC. It was included in the Guardian’s list of the 100 greatest novels, and ranked as number 36 in Penguin Publishing’s survey of its readers’ favorite books. The Norwegian Book Club survey, in cooperation with the Nobel Institute, included Middlemarch in its list of the 100 greatest works in world literature. In 2007, a group of 125 revered authors chose the “Ten Greatest Books of All Time,” which included Middlemarch as #10. And, drum roll please, in a 2015 BBC sponsored poll of book critics from outside the UK, intended to name the greatest British novels of all time, Middlemarch came in as #1. Add to this the testimony of individual authors—Virginia Woolf called it “one of the few English novels written for grown-up people,” and acclaimed contemporary novelists Martin Amis and Julian Barnes both have called it the greatest novel written in English—and it becomes a no-brainer: Middlemarch comes in as number 28 (alphabetically) on my list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

Middlemarch, subtitled “A Study of Provincial Life,” is set in a fictitious English town in the midlands (based probably on Eliot’s hometown of Coventry) forty years prior to its publication date—from 1829 to 1832 and the enactment of the First Reform Bill (the biggest social reform legislation in Britain since, well, ever). It grew out of two separate unfinished novels that Eliot was working on at the time: one of these was entitled “Middlemarch” and was focused on the story of a young provincial doctor named Tertius Lydgate. The other was a shorter effort telling the story of an intelligent but underappreciated woman named Dorothea Brooke. When Eliot had the happy idea of combining the two stories, it created a hugely complex novel with a plethora of characters. The resulting novel, the one we have today, could be said to contain four separate plots: Dorothea Brooke’s life and marriage, Tertius Lydgate’s career as a new and reforming doctor in the town, the rocky courtship of Fred Vinci and Mary Garth, and the downfall of the wealthy Nicholas Bulsrode. These plots at first seem to have little to do with one another. But Eliot’s masterful storytelling brilliantly shows how the actions of one character may well affect the life of another character in one of the other plots, which by the end become completely intertwined.

Dorothea, a 19-year old orphan living with her sister Celia and her uncle Mr. Brooke, is courted by Sir James Chettam, but instead is drawn to the scholar Reverend Edward Casaubon, more than twice her age. Chettam switches his interest to Celia as Dorotha marries Casaubon. On their honeymoon in Rome, Dorothea is disillusioned when she finds her husband has no interst in her intellect. Casaubon’s young disinherited cousin, Ladislaw is attracted to Dorothea, but she considers him simply a friend.

Meanwhile Fred Vincy, eldest son of Middlemarch’s mayor and generally considered an indolent slacker since dropping out of college, is interested in Mary Garth, companion to his rich uncle Mr. Featherstone. He expects to inherit his uncle’s wealth, and would like to wed Mary to make his happiness complete. But Fred, having persuaded Mary’s father Mr. Garth to co-sign on a debt, is unable to repay the money and Garth and his daughter are forced to lose their savings. Garth tells Mary that she ought never to marry Fred.

When Fred becomes ill, he is treated by the new doctor in town, Tertius Lydgate. Lydgate’s newfangled ideas about medicine and about the importance of sanitation make him unpopular with the conservative townsmen. A wealthy landowner named Bulstrode supports him, though, and wants to build a hospital and a clinic in accord with Lydgate’s new ideas, but Lydgate is warned about Bulstrode’s integrity. Meanwhile Lydgate becomes acquainted with Fred’s sister Rosamond Vincy, who has set her cap for him and uses Fred’s illness to get closer to him. Eventually, against his better judgment, Lydgate and Rosamond become engaged.

This is the barest outline of the beginnings of the four plots, and you may begin to see how the love lives of all these couples may become interwoven and affect one another. And the question of what makes for a good marriage runs through the book. Dorothea and Lydgate both wind up in unsatisfying marriages, not having partners who can be true intellectual partners for them. On a related note, Middlemarch also deals with what at the time, and for decades beyond, was called “the woman question.” Dorothea is intelligent, ambitious, and dedicated to improving the lives of her neighbors. Before her marriage she has the notion of redesigning all the living spaces of the tenants on her uncle’s manor. And she marries Casaubon fully expecting to help him in researching his great project, the study The Key to All Mythologies. But she is thwarted at every turn. Toward the end of the book Eliot comments that Dorothea, though she had the makings of a heroic woman like Antigone or St. Teresa, lived “amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state, in which great feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion.”

Many have noted that the novel’s subtitle, “A Study of Provincial Life,” plays on the two meanings of “provincial”: In one sense, of course, it refers to any area of the country that is well away from the capital. In the other, it refers to people who are narrow minded and uncultured. Eliot’s novel is a study of both, but most especially the latter, being almost a satire of the shallowness and unprogressive attitudes of the citizens of Middlemarch, particularly toward the novel’s two protagonists, Dorothea and Lydgate.

But what truly elevates Middlemarch above most other novels is Eliot’s amazing ability to create characters with rich psychological realism. Even her minor characters have a depth and solidity rarely seen, as she shows us how differently various characters think.

As mentioned earlier, everybody was not impressed by Middlemarch on its original publication in 1871. And by the early 20th century it was seldom read. The critic F.R. Leavis is given credit for “rediscovering” the novel in his widely influential book The Great Tradition (1948).But the novel’s greatness could not be hidden from some of the most sensitive first readers. When Emily Dickinson read the novel’s first edition, she wrote to her cousins in April of 1873:

“‘What do I think of “Middlemarch”?’ What do I think of glory—except that in a few instances this ‘mortal has already put on immortality.’ George Eliot was one. The mysteries of human nature surpass the ‘mysteries of redemption,’ for the infinite we only suppose, while we see the finite.”

Let that be the last word on the novel.