https://oleoalmanzora.com/oleoturismo-en-pulpi/ Graham Greene is still considered one of the major British authors of the twentieth century, and the sheer volume of his major novels seems likely to keep him there for the foreseeable future. He achieved both critical and popular success in his career, dividing his time between his serious novels and what he called his “entertainments,” which were often political thrillers. It was a distinction he gave up after the late 1950s, since his “entertainments” were often as significant as his “novels.” John Irving once called him “the most accomplished living novelist in the English language,” and Nobel laureate William Golding called Greene “the ultimate chronicler of 20th-century man’s consciousness and anxiety.”

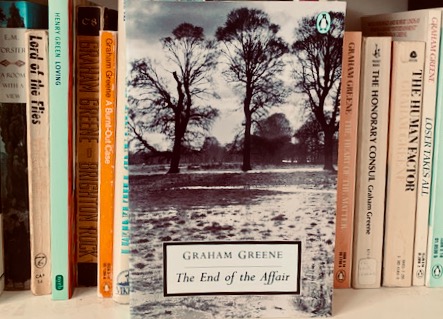

https://www.petwantsclt.com/petwants-charlotte-ingredients/ I myself am bidding to become a Greene completist, at least as far as his novels go: I’ve read twenty-two of the twenty-six that he published (two of his very early ones he repudiated and they were never republished), so I’ve read all but two of the ones he would have wanted me to read. Several of these are modern classics: The Power and the Glory (1940) won Britain’s prestigious Hawthornden Prize, and The Heart of the Matter (1948) the equally prestigious James Tait Black Memorial Prize. He was three times (in 1961, 1966 and 1967) among the three finalists for the Nobel Prize in Literature. I could very easily choose for my own list The Power and the Glory, which appears on Time magazine’s list of 100 best novels in English (since 1923) or The Heart of the Matter, which is also on Time’s list but is also number 72 on the BBC list of the 100 greatest British novels, and number 40 on Modern Library’s list of the 100 greatest English language novels of the century. Brighton Rock (1938) is number 42 on the BBC list, while The Quiet American (1955) appears on The Observer’s list of the 100 Greatest Novels of All Time. I would also include the thriller The Comedians (1966), set in Papa Doc Duvalier’s Haiti, and Greene’s novella The Third Man (1949), a study for the noir film’s screenplay, among my favorites and among his most important works. But when it comes time to choose, I find that the one novel I simply cannot leave out is The End of the Affair (1951), number 31 on the BBC list of the greatest British novels and also appearing on The Guardian’s list of the 100 Best Novels Written in English, on the Daily Mail‘s “A Hundred Novels to Change Your Life,” Parade Magazine’s “The 75 Best Books of the Past 75 Years,” as well as Waterstone’s list of “The Greatest 20th Century Novels.” And The End of the Affair comes in as book number 41 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

Though essentially a romantic love story, The End of the Affair is also psychologically complex, and it was the last of what are known as Greene’s “Catholic novels” (which include also the earlier Brighton Rock, The Power and the Glory, and The Heart of the Matter). Greene called himself a “Catholic agnostic.” Though he was a professed agnostic, he was baptized into the Catholic faith in 1926 after meeting Vivien Dayrell-Browning, a Catholic woman he later married. These four Catholic novels explore Greene’s struggles with the faith and his difficulties with the contradictions he saw in it. In The End of the Affair, the protagonist and unreliable narrator Maurice Bendrix begins this story of his adulterous affair with Sarah Miles by claiming “This is a record of hate far more than of love,” and through the course of the novel we see this hatred move from Sarah’s husband Henry to Sarah herself to, ultimately, the God he does not believe in but who has destroyed his life.

The novel begins in World War II London during the Blitz, and ends just after the end of the war. Maurice Bendrix, a fledgling novelist hoping to make his reputation, wants to write a novel about a civil servant, and in 1942 begins to meet with Sarah in order to gather information about her ineffective civil servant husband Henry. Their meetings soon become passionate, though all the while Bendrix seems convinced that the affair cannot last because of his own irrational jealousy and Sarah’s refusal to consider divorcing Henry.

At a climactic point of the affair, Sarah is with Maurice at his flat when a German bomb strikes the building and Bendrix is knocked cold. When he comes to, he finds a very shaken Sarah, who had been convinced he’d been killed. The day after this incident, Sarah breaks off their relationship without any explanation, a breakup that leaves Maurice feeling resentful and vengeful. He considers suicide and begins to hate Sarah.

One rainy evening some eighteen months later, Bendrix meets Henry in the common area between their neighboring apartments. Henry, belatedly, has begun to suspect his wife of infidelity. Maurice, his characteristic jealousy piqued, decides to hire a private detective to learn just who Sarah’s new lover is, the man for whom she has dropped him.

From the private detective, Parkis, Bendrix learns that Sarah keeps a diary, and that he has seen her regularly visiting a house on Cedar Road. He also gives Bendrix what seems to be a love letter in Sarah’s hand. Bendrix tells Henry what he has learned. Later Parkis steals Sarah’s diary and gives it to Bendrix to read. And that’s all I can tell you if I don’t want to spoil the ending for you. But I can tell you that pretty much everything Bendrix believes turns out to be wrong. And I can also tell you that God figures strongly in the novel’s denouement.

This is a novel that was seemingly close to Greene’s heart. It’s a psychological drama whose structure is reminiscent of an old morality play, with Sarah in the role of Everyman, Bendrix cast as the devil, and God himself in the role of the Good Angel. When Sarah dies about halfway through the book (did I say that out loud?) Maurice is left with no one to hate but the God who has robbed him.

After Sarah’s death, as the novel moves toward its close, Maurice actually moves in with Henry, and when a Father Crompton comes to call on Henry, to try to convince him to give Sarah a Catholic burial instead of a cremation because she had expressed a desire to become a Catholic, Maurice lashes out at the priest, venting his rage at God upon his representative:

There had been a time when I hated Henry. My hatred now seemed petty. Henry was a victim as much as I was a victim, and the victor was this grim man in the silly collar.

To this the priest, seeing through Maurice’s anger to this deep pain, tells him he is “a good hater.” And even though Maurice is confronted by evidence that suggests the possibility that Sarah was in fact a true saint, he angrily shrugs off such hints. We do not see our narrator change in his hatred. After all, he is telling the story after its close, and he began by telling us it was aa record of hate. The book closes with this chilling passage:

I wrote at the start that this was a record of hate, and walking there beside Henry towards the evening glass of beer, I found the one prayer that seemed to serve the winter mood: O God, You’ve done enough, You’ve robbed me of enough, I’m too tired and old to learn to love, leave me alone forever.

Greene was inspired to write the novel by his own affair with Catherine Walston, the American wife of a wealthy British landowner who, at age 30, converted to Catholicism after being inspired by The Power and the Glory. She asked Greene to be her godfather, though they had never met, and they ended up having a long affair. The fact that Greene’s own house was damaged by a bomb during the London Blitz gave him the idea for the novel’s climactic moment, and The End of the Affair was born. Greene dedicated the book to “C”—for Catherine.

The novel was well received, popular, like all Greene’s best fiction, with readers as well as critics. It’s often been admired for Greene’s innovative narrative structure, a mixture of straight narrative, flashbacks, and the use of Sarah’s diary and letters to develop plot points. Greene’s friend Evelyn Waugh, in a 1951 review of the book, called it “a singularly beautiful and moving one.” So beautiful and moving that it remains one of Greene’s most popular novels and has been filmed twice: Once in 1955, shortly after its publication, with Deborah Kerr as Sarah (a role for which she was nominated for a BAFTA Award), Van Johnson as Maurice Bendrix, and Peter Cushing as Henry. It was directed by Edward Dmytryk (fresh from directing The Caine Mutiny), and received a Palme d’Or nomination at Cannes. Forty-four years later, The End of the Affair was filmed again by Neil Jordan, who had won an Oscar for the screenplay of The Crying Game in 1993. Ralph Fiennes played Maurice and Stephen Rea played Henry in this production, while Julianne Moore garnered an Oscar nomination for playing Sarah. Both films are essentially faithful to the book, and are worth your viewing. But once again, don’t watch them in lieu of reading the novel. You don’t want to spoil the reaction you’ll have when you reach the novel’s conclusion—it’s a distinct and worthwhile pleasure that makes the book one of the most lovable in the English language.