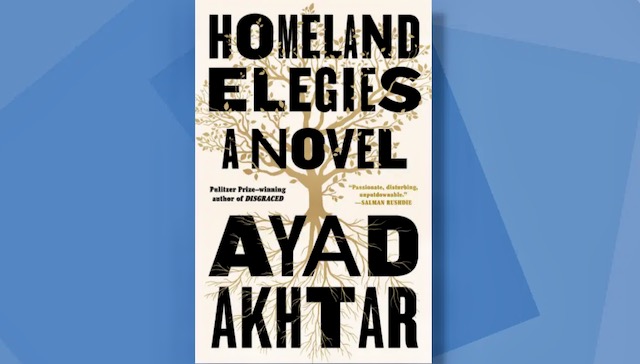

Homeland Elegies

Ayad Akhtar (2020)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/3-12.jpg’ attachment=313′ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Three Tennysons/Half Shakespeare[/av_image]

[av_textblock size=” font_color=” color=”]

Ayad Akhtar’s Homeland Elegies: A Novel certainly does not read like a novel. I mean, the narrator is a guy by the name of Ayad Akhtar, who is the American-born son of physician parents who immigrated from Pakistan. He was born in Staten Island and raised in Wisconsin, and won a Pulitzer Prize for a play he wrote called Disgraced. And he’s writing a book dealing mainly with the experience of being a Muslim in post-9/11 America, particularly in the increasingly xenophobic milieu of a Trump presidency. So far, it looks a lot more like a memoir than a novel.

Furthermore, the book is not a continuous narrative, but consists of eight rather loosely linked chapters that vary from autobiography to episodic fiction to essay to historical and cultural commentary. Is that what we’re calling a novel these days?

Of course it is. This is a novel that is not only post-modern, but also post-truth in the most Trumpian sense. Akhtar has said that he wanted the book to simulate a scroll through social media, during which one might click on a variety of links in a somewhat haphazard way. In an NPR interview, he said

“I wanted to reach a reader today who is addicted to the thrill of breaking news and absorbed in the Instagram scroll feed.”

In that same interview, discussing the line between autobiography and fiction, the author stated, “I wanted to find a form that would express this confusion between fact and fiction which seems to increasingly become the texture of our reality or unreality.” As a result, Akhtar goes on, “I had to pilfer from my life. I had to use fact. I had to convince the reader at various times that what I was writing was real, and yet I’m calling it a novel.” And so we end up with a book that perfectly reflects the Trump-era confusion of fact and fiction, the distrust of objectively factual news stories in favor of the most irresponsible misrepresentation, until we can’t be sure what in the book is real and what is not. Did Akhtar’s father support Trump’s candidacy because he had once actually been his heart doctor? Who knows? Did Akhtar himself fall under the spell of a Muslim hedge fund manager and succumb to the lure of easy money? Maybe. Was Akhtar’s father sued for malpractice in La Crosse? Probably. But who knows?

Philosophically, that uncertain gap between truth and fiction is an underlying theme of the book. Sociologically, Akhtar’s experiences as perhaps representative of the experience of being Muslim in post-9/11 America take center stage. Akhtar delineates his own experiences as representative of mainly white reactions to him after that attack. One lengthy section of the book concerns his experiences in Scranton, Pennsylvania, when his car breaks down. He delineates his interactions with a suspicious state trooper, then with a repair shop whose owner is related to the trooper and pretty blatantly holds him up, doing work on the car that he does not authorize and so giving him a bill he cannot afford. But feeling all the while under scrutiny as a possible terrorist, he cannot complain or make a scene or appear quarrelsome. He even identifies as Indian rather than Pakistani. And he says, “If all this sounds somewhat paranoid, I am happy for you. Clearly you have not been beset by daily worries of being perceived — and therefore treated — as a foe of the republic rather than a member of it.”

On his professional level, also, Akhtar is a conflicted Muslim-American, finding that in some senses the two halves of that designation may be incompatible. Ten years after 9/11, Akhtar the writer (as well as Akhtar, the character in the novel) writes the play Disgraced, in which a Manhattan dinner party goes ballistic with arguments over politics and religion. The dinner’s host, a Muslim named Amir Kapoor, responds to the goading of one of the guests suggesting that he might have felt proud when the planes crashed into the towers with the statement, “If I’m honest, yes.”

Such a climax is shocking, and of course non-Muslims would be anxious to know how much such sentiments reflected Akhtar’s own, or those of his family or fellow Muslims (hence the subsequent deliberate blending of fiction and autobiography in the novel). Nor did the depiction of Amir make him any friends among Muslim-Americans, who may see his complex rendering of Muslim-Americans as feeding negative stereotypes.

The psychological theme of the novel, then, explores this divided self in the author’s depiction of his parents and their own experiences as Muslim immigrants in a racist country that hates immigrants. On the one hand, his father Sikander—at least the character Sikander—is a gung-ho immigrant roused to jingoistic celebration of a country that allows him, as an eminent heart specialist, to amass significant wealth. “Love for America and a firm belief in its supremacy, was creed in our home,” the author/narrator says. This essentially unreflective patriotism, and his previous acquaintance with the Apprentice personality, inspires Akhtar to join the MAGA crowd, and to continue to give blind support to the man even through his post-Charlottesville comments and his anti-Muslim actions—supported him, Akhtar says, “well past the point that any rational nonwhite American (let alone sometime immigrant!) could possibly have justified to himself or anyone else.” Seduced by the American Dream, his father makes a great deal of money—and loses a great deal, mainly through gambling, until the chauvinistic immigrant packs it in and heads back for Pakistan.

For a time Akhtar himself, or his fictional surrogate, is seduced by money and fame, after his Pulitzer in 2013, when he joins the Riaz Rind foundation and begins an ultimately empty flirtation with capitalism and high society. But at the same time, he is pulled in another direction by his mother Fatima who, in contrast with his father, did not much like her new country: as Akhtar puts it, “my mother never found in the various bounties of her new country anything like sufficient compensation for the loss of what she’d left behind.” In fact, it turns out that it was Akhtar’s mother who was the source for that shocking comment from the protagonist of his prize-winning play. After reviewing the tarnished history of American diplomacy in the Middle East, his incensed mother remarks, concerning the bombing of American embassies there (and not about 9/11 in the following decade), “They deserve what they got.” Her bitterness, she believes, is the cause of the cancer that kills her.

The fictional, and the actual, Akhtar avoids the extremes of both his parents. In fact the book begins and ends with his favorite professor, Mary Moroni, who taught him to love American literature, particularly Whitman, while encouraging him to follow his dream of writing, and who also taught him critical thinking. And that meant thinking critically about the country he lived in—to think about America during the Reagan presidency as “a place still defined by its plunder, where enrichment was paramount and civil order always an afterthought.” Her words, he says, were “a corrective to a tradition of endless American self-congratulation.” For one who loves his country, it is important to see its faults as well as its virtues, the more to make it a finer place. Thus in the end, he meets Mary again as a distinguished guest lecturer at her college for a discussion of politics, when challenged by an audience member who asks why, if he sees so much wrong with this country, he doesn’t leave, he can answer in all honesty:

“I’m here because I was born and raised here. This is where I’ve lived my whole life. For better, for worse—and it’s always a bit of both—I don’t want to be anywhere else. I’ve never even thought about it. America is my home.”

The term “elegy” has two meanings in literary vocabulary. An elegy can be, like Milton’s “Lycidas,” a lament for the dead. Or it can be more generally, like Gray’s “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard,” a pensive and reflective poem. For America’s sake, let us hope that Homeland Elegies is the latter, and not the former, kind of elegy.

NOW AVAILABLE

To the Great Deep, the sixth and final novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at http://encirclepub.com/product/to-the-great-deep/

You can also order from Amazon (a Kindle edition is available) at https://www.amazon.com/Jay-Ruud/e/B001JS9L1Q?ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_1&qid=1594229242&sr=8-1

Here’s what the book is about:

When Sir Agravain leads a dozen knights to arrest Lancelot in the queen’s chamber, he kills them all in his own defense-all except the villainous Mordred, who pushes the king to make war on the escaped Lancelot, and to burn the queen for treason. On the morning of the queen’s execution, Lancelot leads an army of his supporters to scatter King Arthur’s knights and rescue Guinevere from the flames, leaving several of Arthur’s knights dead in their wake, including Sir Gawain’s favorite brother Gareth. Gawain, chief of what is left of the Round Table knights, insists that the king besiege Lancelot and Guinevere at the castle of Joyous Gard, goading Lancelot to come and fight him in single combat.

However, Merlin, examining the bodies on the battlefield, realizes that Gareth and three other knights were killed not by Lancelot’s mounted army but by someone on the ground who attacked them from behind during the melee. Once again it is up to Merlin and Gildas to find the real killer of Sir Gareth before Arthur’s reign is brought down completely by the warring knights, and by the machinations of Mordred, who has been left behind to rule in the king’s stead.