https://drcarlosarzabe.com/dr-carlos-arzabe/ How Beautiful We Were

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/3-12.jpg’ attachment=313′ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Three Tennysons/Half Shakespeare[/av_image]

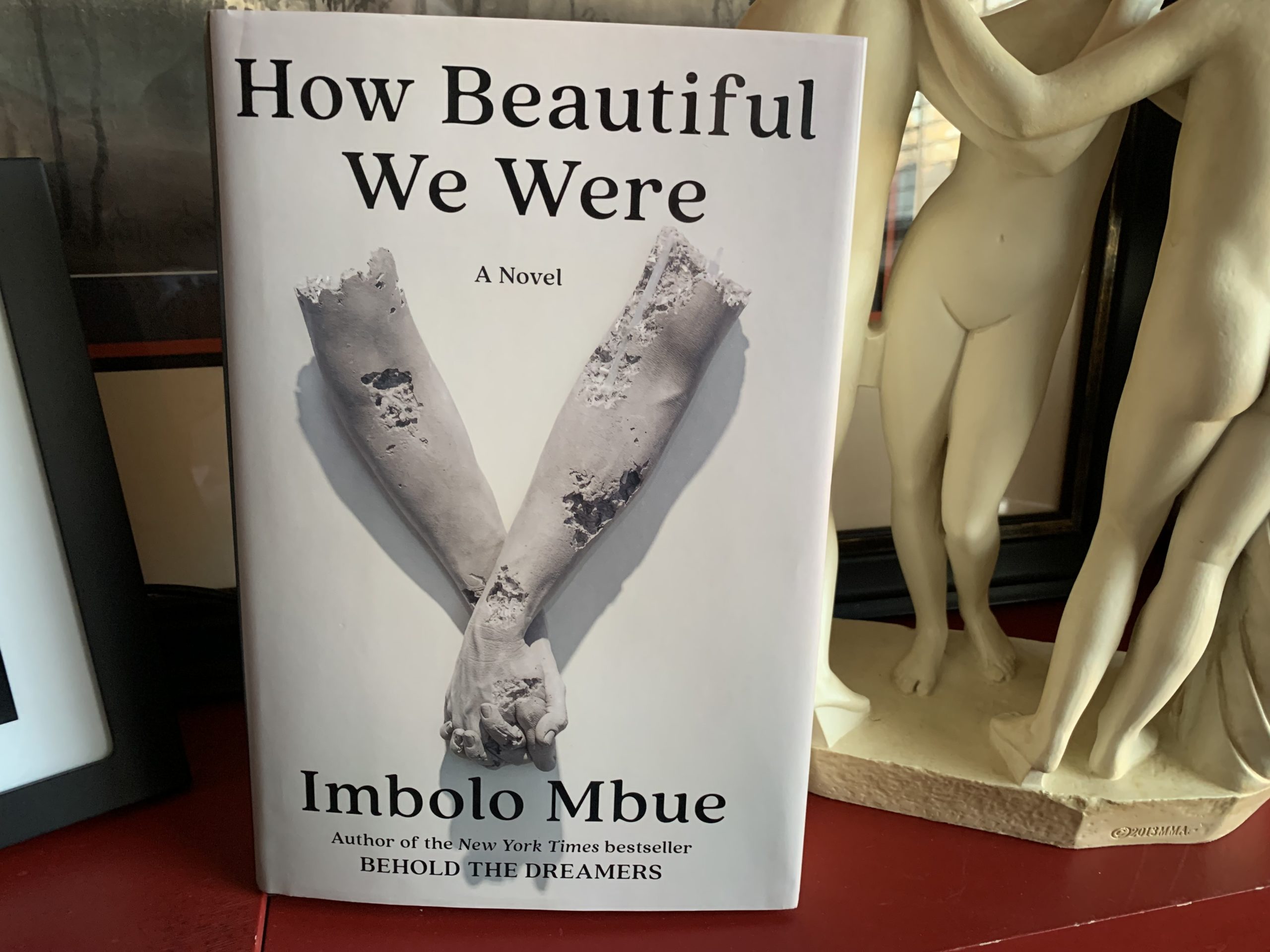

The success of her first novel, Behold the Dreamers, which won the PENN/Faulkner Award for 2016, made her follow-up book, How Beautiful We Were, one of the most anticipated books of 2021. Mbue was born in Cameroon and came to the United States to earn a B.A. from Rutgers, followed by a graduate degree from Columbia. Her debut novel, published during the presidential campaign of 2016, had a very timely theme, exploring the difficulties of immigrants like herself. The second book is at once more focused and more sweeping in its subject matter: It explores the everyday life and problems of a small fictional African village called Kosawa and its struggles against a giant American-based global oil company called Pexton.

“We should have known the end was near,” the novel begins. While readers soon realize that the communal narrator’s “we” comprises the citizens of Kosawa, that first sentence seems to bring us as readers into that circle of “we.” And since the book is chiefly concerned with the destruction of the environment by the faceless, impersonal embodiment of corporate greed, we as readers must, from the beginning, identify with those who, in retrospect, should have known the end was near.

For, as we discover early in the novel, the farmlands around Kosawa have been polluted by recurrent oil spills that have made them infertile. The corporation has poisoned the water of the village so that their children are regularly dying from drinking the waste. The oil company, Pexton, sends a panel of three representatives who visit the village every few months to assure them that the company has nothing but their best interests at heart and plans to clean up the environmental hazards, promises that are never fulfilled. And the country’s “president for life” is a totally corrupt politician whose only interest is in how many millions he can collect for himself by giving Pexton carte blanche to rape his country.

Mbue’s story of Kosawa spans four decades and is told from several different perspectives, but the story is held together by the figure of Thula, a village girl who is ten years old when the novel opens, and about fifty when it ends. In many ways Kosawa is the protagonist of the story, but Thula is the human embodiment of the village. Her chief antagonists are the exploitative Pexton, whose sole concern is profit and which is indifferent to human suffering and human life, and the government of her unnamed country, embodied in the president, whose only concerns are power and greed. In the abstract, one could say Kosawa’s antagonists are the twin scourges of capitalism and neo-colonialism.

Each chapter of How Beautiful We Were is told from a different point of view. The narrators range from Thula herself to other members of her family, including her uncle Bongo, her mother Sahel, her grandmother Yaya, and her brother Juba, to the children of the village who are Thula’s “age mates” (those who are still alive), who during the course of the book pass into adulthood, have their own families, and ultimately their own grandchildren.

Even by October of 1980, when the novel opens, Pexton has been draining oil and polluting Kosawa’s environment for some twenty years, until things have gotten so bad that children are dying in significant numbers. Thula’s brother Juba himself has had a near-death experience, causing their father Malabo to take matters into his own hands and travel to the country’s capital, Bézam, to confront the government and seek redress for Pexton’s dangerous practices. But Malabo and his fellow petitioners mysteriously disappear on their way home from this meeting.

Things soon take a more radical turn. After one of the regular meetings with the three representatives of Pexton, who periodically come to the village to assure them that Pexton is doing everything it can to clean things up and keep the people safe, while in fact nothing is being done and their job is simply to lie, a man named Konga stops the meeting. Though considered the village madman, Konga has formulated a plan: He has stolen the representatives’ car, imprisoned their driver, and proposes to hold the Pexton men captive until Pexton agrees to the villagers’ demands. Enough of the men of the village are so fed up with Pexton’s lies that they go along with the madman’s scheme.

It is probably not a spoiler to acknowledge that this scheme turns out to be madness indeed. It is not only unsuccessful, but it also brings terrible retribution down on the village when government soldiers gun down several villagers in the town square. But the massacre boomerangs on the government, since a western-educated journalist is on hand to secretly photograph the whole thing. When the story appears in American newspapers, the African president has no plausible way of denying the affair.

Pexton, of course, can simply say that the massacre was the government’s response and that they had nothing to do with it. The publicity, however, does get the attention of an American-based organization called The Movement for the Restoration of the Dignity of Subjugated Peoples. This group mounts a lawsuit against Pexton to try to force the company to clean up their act and to fairly compensate the villagers whose children’s deaths the company has been responsible for, and whose land and water they have ravaged. This development takes the story into the U.S. legal system. The suit drags on for years, but the Movement is able to help with certain things. Eventually children have bottled water to drink. Kosawa children like Thula are bused to a school in a neighboring village where they can get a high school education. Scholarship money even becomes available that enables Thula to leave Africa and continue her education at universities in America. At this point Thula seems to be repeating the career of her creator.

At this point the novel transitions from giving a detailed account of a few significant events in the life of Kosawa in the 1980s to a retrospective view of the changes that take place over the next three decades. Thula spends ten years in New York, where she obtains advanced degrees and becomes politicized by her contact with social activists in the States. She writes constant letters home, exhorting her contemporaries not to give up on the goal of ousting Pexton and reclaiming their heritage. When she finally does return to her homeland, to take up a teaching position in a government school in Bézam, she tries very hard for years to rally people in Kosawa and neighboring villages to peacefully protest against the government. She talks down several of her contemporaries who believe that armed rebellion is the only way to finally bring change. She hires a more prominent lawyer to bring a new suit against Pexton. Is she naïve to believe that American courts will solve the issues of her country? It’s probably important here to echo something that the madman Konga says earlier in the novel: “Someday, when you’re old, you’ll see that the ones who came to kill us and the ones who’ll run to save us are the same….No matter their pretenses, they all arrive here believing they have the power to take from us or give to us whatever will satisfy their endless wants.”

To say any more would definitely be too much of a spoiler. In the end, Mbue’s second novel is a devastatingly real look at the ways capitalism and colonialism destroy traditional societies. It’s an indictment of corporate greed and political corruption, but it is also a meditation on how, even in the best of scenarios, the traditional ways embodied in the villagers of Kosawa are doomed to be snuffed out despite the best wishes of the colonizers. The novel is engaging and thought provoking. It is more effective in the first half than in the more wide-ranging retrospective of the last chapters, but it is definitely worth a read.