Tolkien, whose day job was as a professor of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford University, dabbled in world-creation in his spare time from as early as 1917—beginning with his creation of two different elvish languages, Quenta and Sindarin, and the alphabets that go with them. He invented Middle Earth and made up the stories first in order to create a context for the languages he’d created. Sometime around 1936, while grading exams, he invented a creature called a hobbit who lived in a hole in the ground, and he wrote a children’s story about one such creature, Bilbo Baggins, who had an adventure. His subsequent novel The Hobbit became a popular success, and his publisher, Allen & Unwin, encouraged him to write a sequel. Like his character Treebeard the Ent, Tolkien was not keen on doing anything hastily, and having started out his “new Hobbit“in the same vein as his earlier book, he conceived a sweeping epic adventure that expanded after some twelve years of writing into some 1500 pages in six books plus Appendices.

The success of this monster of a book was as much a surprise to him and it was to his publisher: Allen & Unwin were on the fence about publishing Lord of the Rings—it was long and it was not thought of as mainstream fiction, and it would be very expensive to print in post-war Britain where there were shortages of things like paper. Raynor Unwin read the manuscript of Lord of the Rings and told his father, who ran the company, that they would probably lose a thousand pounds in publishing it, but that it was a work of genius. His father said, “Well, for a work of genius I’ll spend a thousand pounds.” But to hedge their bets, the publisher gave Tolkien no advance payment, and told him they would pay no royalties on the book until they had made back their investment. The incentive they gave him was that once they made back their initial costs, they would pay him half of all the profits. But they assumed they’d never have to pay him anything. To everyone’s surprise, Lord of the Rings ended up selling something like 200,000,000 copies over the years. So Tolkien’s contract ended up being the most lucrative publishing contract ever signed.

Aside from the popularity, the acclaim garnered by Lord of the Rings was unprecedented for a work of fantasy. It appeared on the Time magazine list of the greatest novels since 1923, and on the Observer’s list of the 100 greatest world novels. It was 49th on the Penguin list of “must read classics” as chosen by their readers, 26th on the BBC list of “Greatest British Novels”, and 11th among English language novels on the “Greatest Books of All Time” website, an aggregate of more than 400 great books lists. More impressive, it was the 5th most loved book in the PBS “Great American Read,” 3rd on the Library Journal’s “Books of the Century” list, and 2nd on the New York Times Book Review’s reader survey naming the “Best Book of the Past 125 Years.” And it came in as number one on Waterstone’s “Books of the Century” list, number one on NPR’s list of the “Top 100 Science-Fiction/Fantasy Books,” number one on the Australian “Big Read,” number one on the German “Big Read,” and number one on the original (2003) BBC “Big Read.” In 1999, Amazon.com named Lord of the Rings the “Best Book of the Millennium.” And of course it appears here as book #85 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

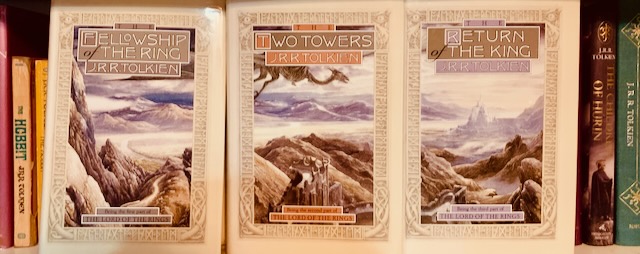

It seems futile for me to try to briefly summarize the complex plot of this three-volume novel, and the story is so well known to the tens of millions who have read Lord of the Rings and the hundreds of millions who have seen the faithful Peter Jackson film trilogy that it hardly seems necessary. But in case you are the one human who has done neither, or in case you need a quick refresher, let me give it a try: In The Fellowship of the Ring (volume I),The wizard Gandalf comes to realize that the magic ring found by the hobbit Bilbo Baggins (in The Hobbit) is the “One Ring to rule them all” created by the Dark Lord Sauron in the previous age of Middle Earth, and convinces Bilbo to give the ring to his nephew Frodo and leave Hobbiton for the Elves’ kingdom of Rivendell. Years later, Gandalf returns to warn Frodo that Sauron has sent his spies, nine black riders, to search for the Ring. Frodo and his friends Sam, Merry and Pippin set off to leave the hobbits’ homeland, the Shire, and, meeting the Ranger Aragorn on the way, are guided to Rivendell. In a council convened by Rivendell’s king Elrond, it is decided that the Ring, which corrupts anyone who wears it, cannot be used as a weapon against Sauron but must be destroyed in Mount Doom, in Mordor (Sauron’s kingdom) where it was forged. Frodo volunteers to carry the Ring to Mordor, supported by his three hobbit friends, Gandalf, Aragorn, the elf Legolas, the dwarf Gimli, and Boromir, son of the steward of Gondor, the human kingdom that borders Mordor. On the journey, Gandalf falls while battling a monstrous Balrog, the fellowship is aided by Galadriel, queen of the elven territory of Lorien, and Boromir, maddened by the lure of the Ring’s power, attacks Frodo and tries to take the Ring from him. He is killed by a band of Orcs, the Dark Lord’s army, who kidnap Merry and Pippin. Frodo and Sam go off together to enter Mordor. As the story advances through the second volume (The Two Towers), Aragorn, Legolas and Gimli chase the Orcs who had taken Merry and Pippin into Rohan, a kingdom traditionally allied with Gondor. Aragorn is revealed to be the heir to the throne of Gondor. Saruman, head of Gandalf’s council of wizards, treacherously betrays the alliance and joins Sauron. Frodo and Sam, making their way toward Mordor, are being followed by Gollum, the creature who had owned the One Ring for centuries and who wants to get it back. Using the Ring as an incentive, Frodo convinces Gollum to lead them into Mordor without being seen. As the climax of the story approaches (in Return of the King, the third volume), a great battle is fought before the gates of Gondor, as Frodo and Sam struggle mightily to reach Mount Doom. I won’t, of course, reveal the final outcome of the novel, but I’m pretty sure most of you already know it.

But why did it sell so well? One reason is Tolkien’s use of what Carl Jung calls archetypal motifs—motifs that are part of the human psyche that appear in mythologies the world over, such as the quest, the father figure (Gandalf), the Shadow involving a descent into an underworld (Mordor): any work of literature that contains universal elements like these (e.g. Star Wars) will appeal to readers. But more specifically, the first readers of Lord of the Rings saw it as an allegory of the Second World War, during which much of the manuscript was composed: the importance of defeating Nazism (Hitler =Sauron) which had threatened to swallow up England, and could only be defeated through great sacrifice. But when the work really took off in popularity was in the later 1960s, when young people at the time saw it as applicable to things they were concerned about. The One Ring suggested nuclear weapons—those symbols of the absolute power that corrupts absolutely. Treebeard and the Ents, who decisively resist the destruction of the natural environment by the traitor Saruman, were early spokespersons for environmentalism. And there was the draw of escapism from a world that seemed to be going all wrong, into a world where good and evil were more clearly delineated.

But Tolkien himself insisted that The Lord of the Rings was not allegorical—he disliked the didactic and blatant Christian allegory apparent in his friend C.S. Lewis’s Narnia books. The story was, however, “applicable,” he said, to the experiences of contemporary readers. And succeeding generations have always found something in their time to which the story seemed applicable. Plus, of course, there are the hobbits. The unassuming, everyday little people, to whom everyone can relate, are the biggest reason for Tolkien’s success—and they are why The Silmarillion and later posthumous publications have never sold as well as The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings.

Other serious literary scholars have criticized the work as escapist, the characters as undeveloped, the language as overwrought, and the theme as cliché. As I’ve said elsewhere, these critics miss the point that Tolkien hasn’t written a novel in the conventional sense, but has written a “fairy story,” the aims of which he clarified in his significant 1939 lecture “On Fairy Stories.” Fairy stories, he argued, are not simply for children. Historically they come from the great “cauldron of story” from which all mythic elements derive. As “secondary creators,” the authors of fairy stories emulate the primary creator, God Himself, and readers must accept them with an imaginative “secondary belief.” As for “escape,” Tolkien notes that there are two kinds of escape: one involves a desertion of responsibility; the other is like the escape of a refugee from a tyrannical regime. Fairy stories are the latter: we escape the ugliness of the contemporary human condition and see the world in a new way. Finally, and most importantly, the fairy story contains a sudden reversal and what Tolkien calls a eucatastrophe (a mirror image of the peripetia and catastrophe of tragedy). This involves a sudden happy turn of the plot that reflects what the Christian Tolkien regarded as the transcendent truth of miraculous Grace. For him, this was at least as realistic as the disastrous ending of a tragedy.

The enormous popularity of Lord of the Rings made fantasy, as Tolkien conceived it, a part of the mainstream literary world, and particularly after Lord of the Rings, no one could ever write fantasy again without taking Tolkien into account. Some, like J.K. Rowling, do it fairly obviously and unapologetically. Some, like Philip Pullman (in the His Dark Materials trilogy) use elements like the quest, the medieval-like setting, the helpful animals, but make a clear departure from some aspect of Tolkien’s work, in Pullman’s case a departure from Tolkien’s theistic world view reflected in his use of eucatastrophe. Some, like Terry Pratchett in his Discworld series, borrow a lot of motifs from Tolkien but take a comic twist, making fun of Tolkien’s detailed maps, for instance, by giving readers a blank map of his imaginary world. And another popular contemporary fantasy writer, George R.R. Martin, emulates Tolkien in numerous ways—he’s created a medieval-like setting, his world is as complete and self-contained as Tolkien’s (though perhaps shallower in its history), he uses dragons and a very human dwarf, huge battles and supernatural evil. But his worldview deliberately undercuts Tolkien’s optimistic, heroic, and spiritual presentation, and gives us a mock-medieval world that is dreary and dark. Everybody doesn’t write as Tolkien did, but everybody writes in response to Tolkien.