Jackie

Pablo Larrain (2016)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Ruud Rating

4 Shakespeares

[/av_image]

One of the most acclaimed films of the silent era—indeed, a film often listed among the “top ten” films of all time—is Carl Theodore Dreyer’s 1928 classic The Passion of Joan of Arc. Dreyer’s script was compiled directly from the written transcripts of Joan’s 1431 trial, and he strove to give it an almost documentary realism. It follows Joan’s interrogation before her judges, her “confession” before a false confessor sent to her cell, her abjuration declaring that her visions had, after all, been false, and her subsequent rejection of that abjuration, leading directly to her martyrdom at the stake, and ultimately to her canonization as “Saint Joan,” which had occurred just two years before Dreyer started filming. Most notable in the film is the fact that it is shot to a large extent in close-ups, so that audiences could read every nuanced emotion—faith, horror, fear, sorrow, doubt, courage, victory—in the face of his astonishing star, Renée Jeanne Falconetti in her much-celebrated and only film appearance.

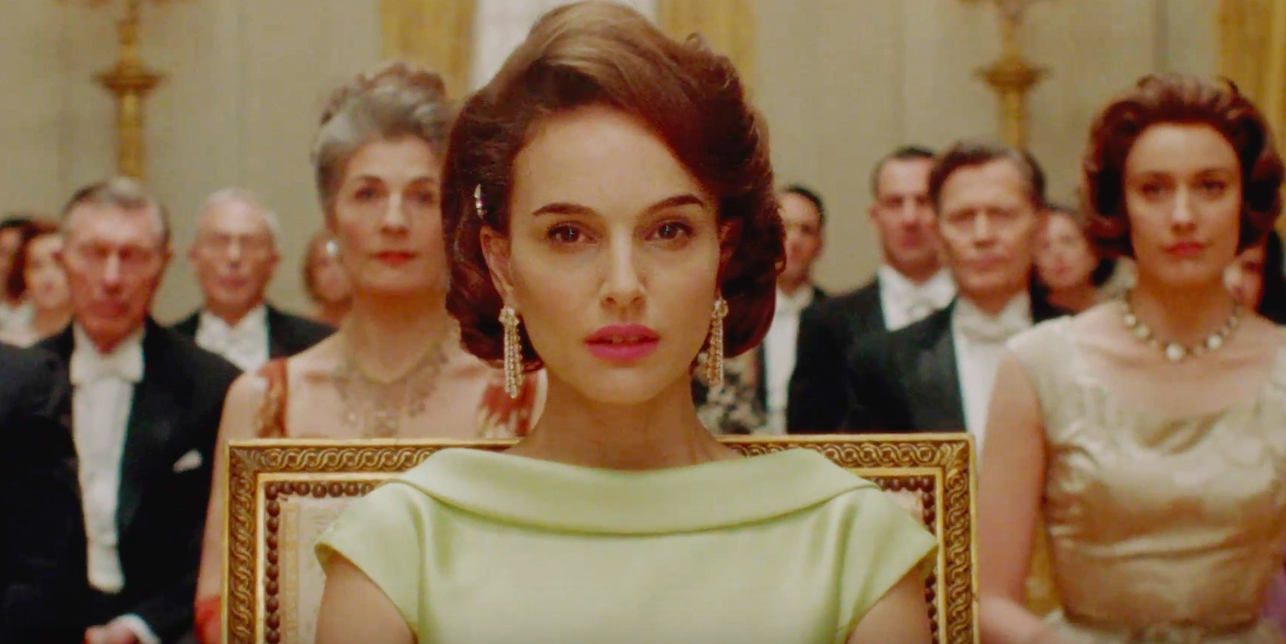

I could not help thinking of Dreyer’s film while watching Pablo Larrain’s new film Jackie with its much-celebrated leading lady, Natalie Portman. Like Dreyer’s film, it is shot to a very large extent in close-up, and as with Falconetti, Portman’s face is constantly under the camera’s scrutiny. I’m sure that one of Larrain’s reasons for this choice was to demonstrate visually the situation of Jacqueline Bouvier Kennedy, the iconic first lady, in the days immediately following the shocking assassination of her husband: her every move at that most personal turning point in her life performed under the microscope of public scrutiny. But the effect of this choice is to allow the audience, as with Falconetti, to read every minute change in emotion—sorrow, terror, anger, frustration, haughtiness, grief, doubt, determination—on Portman’s face. Through her we experience what seems first-hand the assassination, death, and grieving of the president. It’s hard to imagine that a filmmaker like Larrain would be unaware of Dreyer’s powerfully influential film, and it seems quite possible that, consciously or unconsciously, Larrain was channeling Dreyer’s technique.

Certainly Jackie is under great duress, as was Joan. Like Joan, she spends much of the film answering questions and telling her own story, in Jackie’s case to a journalist (Billy Crudup) rather than to an inquisition. As Dreyer’s movie used the actual record of Joan’s trial for its script, Jackie relies heavily on a published Life magazine interview with Mrs. Kennedy done a week after the assassination. Jackie also is shown making a kind of confession to an actual priest (John Hurt), a confession that parallels and contrasts with her answers in her journalist interview. Both Joan and Jackie are forging a myth, Joan unwittingly and Jackie with deliberate calculation, but both are overcome by doubt at one point and seem to back away from their respective mythmaking: Joan, swayed by the prospect of torture and the authority of the Church, abjures the divine origin of her voices; Jackie, swayed by the trepidation of those round her, including Robert Kennedy, that the sort of open-air funeral parade in emulation of Lincoln’s is too dangerous in the violent atmosphere of the country following Lee Harvey Oswald’s own murder, cancels the parade. But Joan recants her abjuration, and Jackie rethinks her cancellation and goes ahead with the solemn procession, and in both cases a myth is created.

Not that Larrain, or screenwriter Noah Oppenheim, means to suggest that Jackie is a martyr or a saint. But as The Passion of Joan of Arc focuses on the Christ-like “passion” of her martyrdom, so that Joan becomes a Christ-figure in the movie; in Jackie the first lady holding the shattered head of her husband in her lap as his limousine speeds to the Dallas hospital, forms a kind of pieta, and Jackie becomes a kind of Virgin Mary figure, whose sorrow itself became mythic.

The film is framed by the interview with a reporter (simply called “the journalist” in the credits) that takes place in the Kennedy family’s Hyannis Port home the week following the assassination. The unidentified journalist is loosely based on Theodore H. White, the Life magazine reporter who in fact interviewed the former first lady on November 29, 1963. The film depicts Jackie very consciously seizing the opportunity to control the narrative of JFK’s legacy, and she has granted the interview with the stipulation that she must approve of everything written in the published article. That the story will be deliberately shaped toward a predetermined end is clear when Crudup mentions her smoking in passing and Jackie, holding her cigarette defiantly, clarifies: “I don’t smoke.” The journalist’s questions range over the first couple’s entire relationship and political life as well as the assassination and the days following, and thus the film follows an associative structure, full of flashbacks that come to Jackie as she speaks, rather than following the typical biopic’s strict chronological order.

We spend a good deal of time reliving the 1962 televised tour of the White House that was the high point of Jackie’s public persona as first lady. We also get behind the scenes after the assassination, see friction with Lyndon and Lady Bird Johnson, see Robert Kennedy’s protectiveness of Jackie and attempts to direct events with his own agenda, and see Jackie’s practical fears about where she is going to live and what she is going to tell her small children. But we also see her shaping the narrative, suggesting to the journalist what would become the memorable keystone of White’s Life article: JFK, she tells him, loved the musical Camelot, and she felt that the final song in Lerner and Lowe’s 1960 script summed up her feelings about the sudden unexpected loss of the president: “Don’t let it be forgot, that once there was a spot, for one brief shining moment, that was known as Camelot.” White agreed, ended his article with that reference, and the rest is history. Or, more accurately, the rest is myth.

Counterbalancing this very calculated interview, and against the graphically realistic aspects of the film’s depiction of the assassination and its aftermath, including the recreation of iconic scenes captured in images from those tense days—LBJ’s swearing in on Air Force One, Jackie’s blood-spattered pink Channel suit, her black-veiled figure holding the hands of John-John and Caroline or marching between Robert and Edward Kennedy behind the coffin—Larrain and Oppenheim have taken the bold step of including the completely imagined interview with the priest. Here they engage in a good deal of speculation, wondering what might really have been happening inside Jackie’s head, behind the poised public figure and the calculating interviewee. Here, the public mask down, the fictional Jackie is able to give free rein to her true feelings, from her resentment of JFK’s extramarital affairs to her sorrow over her lost children to her doubts about religion to her thoughts of suicide. The feelings expressed ring psychologically true, and Larrain and Oppenheim ask us to entertain the plausibility of such emotions within the publicly very poised and reserved first lady.

Portman is nothing short of spectacular in the role, which keeps her in front of the camera for virtually every shot of the film, and she will be hard to beat come Oscar time. Peter Sarsgaard manages to give us a nuanced and believable Robert Kennedy without trying to do an impression of JFK’s fellow martyr by mimicking his voice or mannerisms. Greta Gerwig is sympathetic as Nancy Tuckerman, the first lady’s friend and aide, and Max Casella is appropriately slimy as the new president’s assistant, bent on putting forward LBJ’s interests whatever the Kennedys want to do. Mica Levi’s dark score accentuates the film’s sorrowful tone. Chilean director Larrain (whose film about his country’s greatest poet Neruda will be released very soon) is masterful in his first English-language film, and Oppenheim’s script blends history and imagination brilliantly.

I admit that I did not originally intend to rate this film so highly, but since I find I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it since I saw it nearly a week ago, I feel compelled to give it four Shakespeares. Go and see what you think yourself.

[av_notification title=’Note’ color=’green’ border=” custom_bg=’#444444′ custom_font=’#ffffff’ size=’large’ icon_select=’yes’ icon=”]

Click here for book information:

knightsriddleflier-2

[/av_notification]

.