James Baldwin is one of the most significant American writers of the twentieth century, across several genres, but perhaps most importantly in his fiction. His work deals with themes of sexuality, race, and class, and are vivid contributions to the civil rights movement and the gay liberation movement. His 1962 novel Another Country is, perhaps, his most famous, probably because it deals openly with themes and situations that were taboo at the time, and Another Country does appear on the Penguin list of 100 favorite books voted on by readers. But I have to confess that I didn’t like Another Country, and fell asleep continually while reading it—and I did vow that I wouldn’t include books I fell asleep to on my “100 Most Lovable Books in the English Language.”

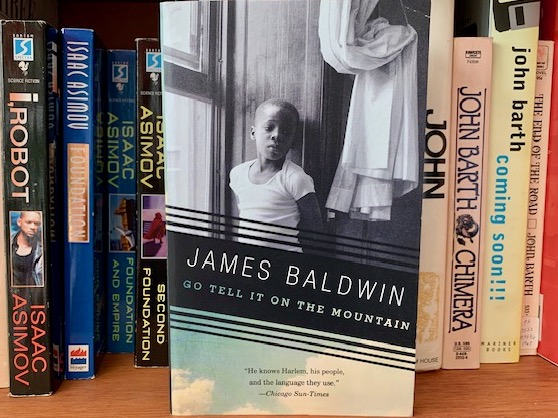

I thoroughly enjoyed Baldwin’s first novel, though—1953’s Go Tell It on the Mountain—and that’s book #9 on my favorites list. Go Tell It on the Mountain is a semi-autobiographical story that culminates in 14-year-old John Grimes’ born-again experience as he physically struggles on the floor of his stepfather’s storefront church. It comes in at No. 39 on the Modern Library list of “Best English-Language Books of the 20th Century,” and also made Time magazine’s 2005 list of the “100 Best English Language Novels since 1923.” Thus, along with Richard Wright’s Native Son and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man, Baldwin’s novel forms a kind of triumvirate of the most significant novels by African Americans between the Harlem Renaissance and what we usually think of as the Civil Rights Movement.

But Baldwin’s book is simultaneously broader and narrower in its concerns than either Wright’s or Ellison’s. It is broader in that it is about more than being Black in America. It’s also about universal concerns like growing up, sexuality and sexual identity, faith and its loss, love and its loss. It is narrower in that it really doesn’t try to tell us about Black experience in a white society. Rather it focuses on one very specific individual—teenaged John Grimes, in a very specific family—one in which his abusive stepfather is a Pentecostal preacher who loves his own son Roy, John’s unreliable brother, but cannot bring himself to love John; in a very specific place—Harlem in the 1930s; on a very specific day—John’s birthday. Baldwin makes no implication that John’s experience is the quintessential metaphor for all African Americans everywhere. But readers will extrapolate some general truths from the experiences of this single family.

What Baldwin’s book does more convincingly and through the truth of personal experience is document the significant role of the church in African American life, both in its positive function of unifying the community and providing inspiration, and also in its negative aspects as a source of moral judgment and exclusion. Baldwin was well aware of these aspects, having been brought up in them, and, like John in the novel, having had a religious awakening at the age of 14 and having become a preacher himself, until he eschewed his faith.

Baldwin divides the novel into three sections. The first part begins as John wakes up on his birthday, wondering if anyone in his family is going to remember what day it is. Elizabeth, his mother, is arguing with Roy about their father, Gabriel, who is aloof and authoritarian and ready to enforce his dictums with beatings. When John thinks everyone has forgotten his birthday, his mother gives him some money to buy himself whatever he wants as a present. He uses it to attend a movie, one of the things his father forbids. When he gets home, he finds that Roy has been in a fight in which he was stabbed, and Gabriel is blaming Elizabeth for Roy’s wild behavior. Florence, Gabriel’s sister, tries to intercede, but Gabriel strikes Elizabeth anyway, and then beats Roy for defending his mother. The section ends with John joining Elisha, his church’s youth minister, in cleaning the church his family attends, and Gabriel, Elizabeth, and (to John’s surprise) Florence entering the church to attend the evening service.

The second part of the book, titled “The Prayers of the Saints,” is a brilliant tour de force in which Baldwin presents us with the entire complex backstory of this family while never straying from the self-imposed straight chronological narrative of this single day in John’s life, a classical unity of time in which is revealed a classical family curse. He does it by allowing us to overhear the unspoken prayers of all the novel’s chief characters as they rehearse before God their secret sins. The section begins with the prayer of John’s aunt Florence, Gabriel’s sister, who has nearly forgotten how to pray, it’s been so long. She reveals her resentment of her brother dating back to childhood, when Gabriel’s drinking and gambling drove her to leave their southern home on a train for New York, where she had married, and lost, a good man. She also remembers her friend Deborah, Gabriel’s first wife, who knew that Gabriel had an illegitimate son in Chicago.

In Gabriel’s prayer, he remembers his conversion after a night of wild carousing, remembers his turning preacher and his defending Deborah at a revival meeting when others shunned her for having been raped at 16. He also remembers his first son, the illegitimate Royal, now dead through his own debauched life, and whose mother Gabriel had abandoned when she became pregnant, giving her money to start over in Chicago.

Elizabeth prays, recalling her own unhappy childhood, in which her mother died and an aunt took her away from her father. She recalls her lover Richard, who suffered unjustly at the hands of the police (Black Lives mattered then, too) and died before she had given birth to John. In New York, she had met Florence, who introduced her to her brother Gabriel. Elizabeth comes out of her prayer when she hears John, lying on the floor and overcome with the power of the Holy Spirit.

The climactic part three of the book, called “The Threshing Floor,” focuses on John himself, writhing on the floor of the church in the throes of the Holy Spirit. Throughout the book, the adolescent John has been struggling with his own sexuality and his church’s attitude toward sin. His thoughts and his natural inclinations, he feels, threaten to separate him from God: “You is in the Word or you ain’t—ain’t no half way with God.” Prior to the service, John had been roughhousing with Elisha, whom he admires deeply—a struggle that he compares to Jacob wrestling with the angel. In a way that seems radical by today’s standards, but which has a history in English poetry that goes at least as far back as Donne—“Imprison me, for I /except you enthrall me never shall be free,/ nor ever chaste, except you ravish me”—Baldwin equates the physical ecstasy of sex with the spiritual ecstasy of religious fervor: John is enthralled by the way Elisha’s “thighs moved terribly against the cloth of his suit,” and as the Holy Ghost speaks to him on the church floor he experiences “a tightening in his loin strings” and “a sudden yearning tenderness for holy Elisha; desire, sharp and awful as a reflecting knife, to usurp the body of Elisha, and lie where Elisha lay; to speak in tongues, as Elisha spoke, and, with that authority, to confound his father.”

Baldwin would not write openly about a homosexual relationship until his next novel, Giovanni’s Room, in 1956. But it is clearly suggested in this novel, though it is not a crucial element in the plot since any form of sexuality would cause the 14-year-old protagonist shame and confusion in the stifling atmosphere of this particular tradition. John hopes that his born-again experience will bring him closer to his stepfather. You can probably guess how well that works. I won’t give away the ending, but I will say that it is more positive than you might imagine. For a book that deals with violent conflict with a difficult father, sexual ambivalence, religious guilt and shame, and, oh yeah, living in a racist society, it’s surprisingly affirmative—as if something has been exorcised, something has been blessed. If you haven’t read it, you ought to.