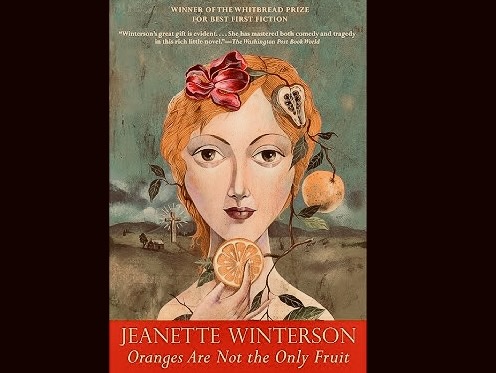

Tramadol Online Jeanette Winterson’s semi-autobiographical 1985 novel Oranges Are Not the Only Fruit is a novel that, according to Winterson herself, bookstores at first found difficult to categorize. When it first came out, they usually placed in the cookbook section. When it began to gain recognition as a “lesbian coming of age” novel, it was placed among the LGBTQ literature. Winterson has objected to this kind of pigeonholing, saying “I’ve never understood why straight fiction is supposed to be for everyone, but anything with a gay character or that includes gay experience is only for queers.” As the novel became more generally recognized for its themes of faith and organized religion, and growing up in difficult family situations, betrayal by friends, lovers and parents, as well as same-sex relationships, it began to be classified with more mainstream popular fiction. And since the novel won Winterson Britain’s prestigious Whitbread Award for a First Novel, it has been included in the academic qualification program for England, Wales and Northern Ireland called the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE), specifically on the A-level module “Literature Post-1900.” So goodbye cooking section, hello modern classics.

Tramadol Cheapest Online Still, I was unfamiliar with this novel and with Winterson herself until I found Oranges are Not the Only Fruit coming in as number 56 on the BBC’s 2015 list of “The 100 Greatest British Novels.” I suspect that this is because Winterson, like some other British authors, is not as well known in the U.S. as in the UK. I read the book and was so impressed that I immediately considered it a good candidate for the list I was compiling of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.” I found on further examination that Winterson’s book appears as number 10 on Good Housekeeping’s 2021 list of “100 Best Books to Read by Women Authors,” and as number 37 on the Guardian’s 2003 list of the “50 Best-Loved Novels Written by a Woman (United Kingdom, Past or Present).” It also appears on the 2014 Amazon.com (UK) list of “100 Books to Read in a Lifetime,” the New York Public Library’s 2020 list of “125 Books We Love for Adults,” and the 2004 list of “50 Essential Reads by Contemporary Authors” published by the UK’s Orange Prize for Fiction (now called the “Women’s Prize for Fiction”). And of course it is included here as book number 98 (alphabetically) on my list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

Orange Are Not the Only Fruit is a semi-autobiographical novel based in part on Jean Winterson’s own life growing up in the town of Accrington, Lancashire. The protagonist’s name, like her creator’s, is Jeanette. The young Jeanette has been adopted by an Evangelical Christian family belonging to the Elim Pentecostal Church (a fundamentalist and revivalist Pentecostal congregation). Jeanette believes she is destined to become a missionary, and her parents and her pastor encourage her in this ambition. As an adolescent, though, Jeanette becomes attracted to another girl, and this causes conflict with her church, her beliefs, and her mother.

The novel opens as Jeanette tells of her life with her adoptive family, in which her mother homeschools her chiefly by having her read the Bible, and telling her she is destined to become a great missionary for the Lord. This lasts until she reaches the age of seven. Two significant things happen to her at that age: first, she loses her hearing, and her mother and the rest of the congregation believe she is in a state of rapture, until one of the churchwomen, Miss Jewbury, realizes she is ill, and Jeanette is treated at the hospital and her hearing restored. Secondly, the local authorities tell her mother she must send the girl to school. Jeanette, never having met anyone outside the narrow circle of her own church, is reluctant to attend public school. She is essentially an outcast at school because of her fundamentalist beliefs that dominate her conversation as well as her school essays and projects, until the teacher, Mrs. Vole, says she is scaring the other students with her constant talk of Hell. Jeanette’s mother is delighted by this news, but Jeanette tones down her evangelism—though this does not make her any more popular with her peers.

As she grows into adolescence, Jeanette begins to silently disagree with some of the teachings and sermons of her church, though she remains devoted to her mother and her mother’s great passion, the “Society of the Lost.” She also begins to become aware of her sexuality. She is attracted to a girl named Melanie who works at a fish stall, and gets a job working Saturdays at a nearby ice cream parlor, and becomes friends with Melanie.

Jeanette brings Melanie to her church, and the girl is converted on her first visit. Subsequently she spends a good deal of time at Jeanette’s house for Bible study, until the two begin a love affair. After she tells her mother of her love for Melanie, her mother reports her behavior to the church pastor, who confronts the pair. Melanie repents her “sin,” but Jeanette leaves the church and takes refuge with Miss Jewsbury, who is herself a lesbian. But the next day, the church elders attempt to exorcise Jeanette’s demons, laying hands on her for fourteen hours, but she still refuses to repent, after which her mother locks her in a room of their house for thirty-six hours without food. Finally, Jeanette pretends to repent in order to eat. As far as her church believes, God has ordained that Jeanette should only be attracted (and subjected) to men. But in her own mind, she sees no difficulty in loving both God and Melanie:

As far as I was concerned men were something you had around the place, not particularly interesting, but quite harmless. I had never shown the slightest feeling for them, and apart from my never wearing a skirt, saw nothing else in common between us.

In the aftermath of this crisis, Meanie disappears and Jeanette becomes more involved in the church, now teaching Sunday school and even preaching in preparation for her vocation as missionary. But that’s as far as I’ll go to avoid any spoilers about the novel’s climax and denouement. But clearly, Jeanette will have to choose between her church’s particular doctrines and the truths her own life has taught her. At one point she muses:

But where was God now, with heaven full of astronauts, and the Lord overthrown? I miss God. I miss the company of someone utterly loyal. I still don’t think of God as my betrayer. The servants of God, yes, but servants by their very nature betray. I miss God who was my friend. I don’t even know if God exists, but I do know that if God is your emotional role model, very few human relationships will match up to it. I have an idea that one day it might be possible, I thought once it had become possible, and that glimpse has set me wandering, trying to find the balance between earth and sky. If the servants hadn’t rushed in and parted us, I might have been disappointed, might have snatched off the white samite to find a bowl of soup.

Thematically, the novel explores religion, sexuality, and family relationships, and thus perfectly suited to YA readers going through such explorations themselves. It is also a very literary novel, in the sense that Waterson’s own wide and thoughtful reading lies behind much of the novel. It is structured, first, into eight chapters, entitled Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, Deuteronomy, Joshua, Judges, and Ruth—the first eight books of the Bible. And each chapter contains allusions to the biblical text for which it is named. There are further references to Jane Eyre, William Blake, John Keats, Christina Rossetti, W.B. Yeats, Middlemarch, and other authors or texts. Jeanette was raised on stories (among them Jane Eyre, to which she eventually discovers her mother changed the ending). Her mother also feeds her oranges at significant points in her life in order to make her feel better. Hence the title (which Winterson attributes, with deliberate falsehood, to Nell Gwynn, mistress of Charles II). The point seems to be that there are other stories available to Jeanette than those her mother feeds her. There are also fruits other than oranges—including, no doubt, the forbidden fruit of Genesis—that sin which may be Jeanette’s “other” fruit.

Given the powerful and sometimes heartbreaking subject matter of the novel, you might expect it to be heavy and very serious in tone. Nothing could be further from the truth. There is a humorously ironic tone through most of the novel, a colloquial and good-humored voice, and an uplifting optimism in spite of all evidence to the contrary. There are also a number of imaginative flights in the text that take the form of short stories, drawn from Arthurian legend, from fairy tales, from Old Testament narratives, which seem digressive at first but which apply directly or indirectly to incidents related in Jeanette’s narrative. Despite some distressing setbacks in the story, it is ultimately a joy to read.

There was a popular award-winning BBC television adaptation of the novel that aired in 1990. I’m not sure whether or not this is still available here, but if you do find it, please read the novel first. You won’t be sorry.