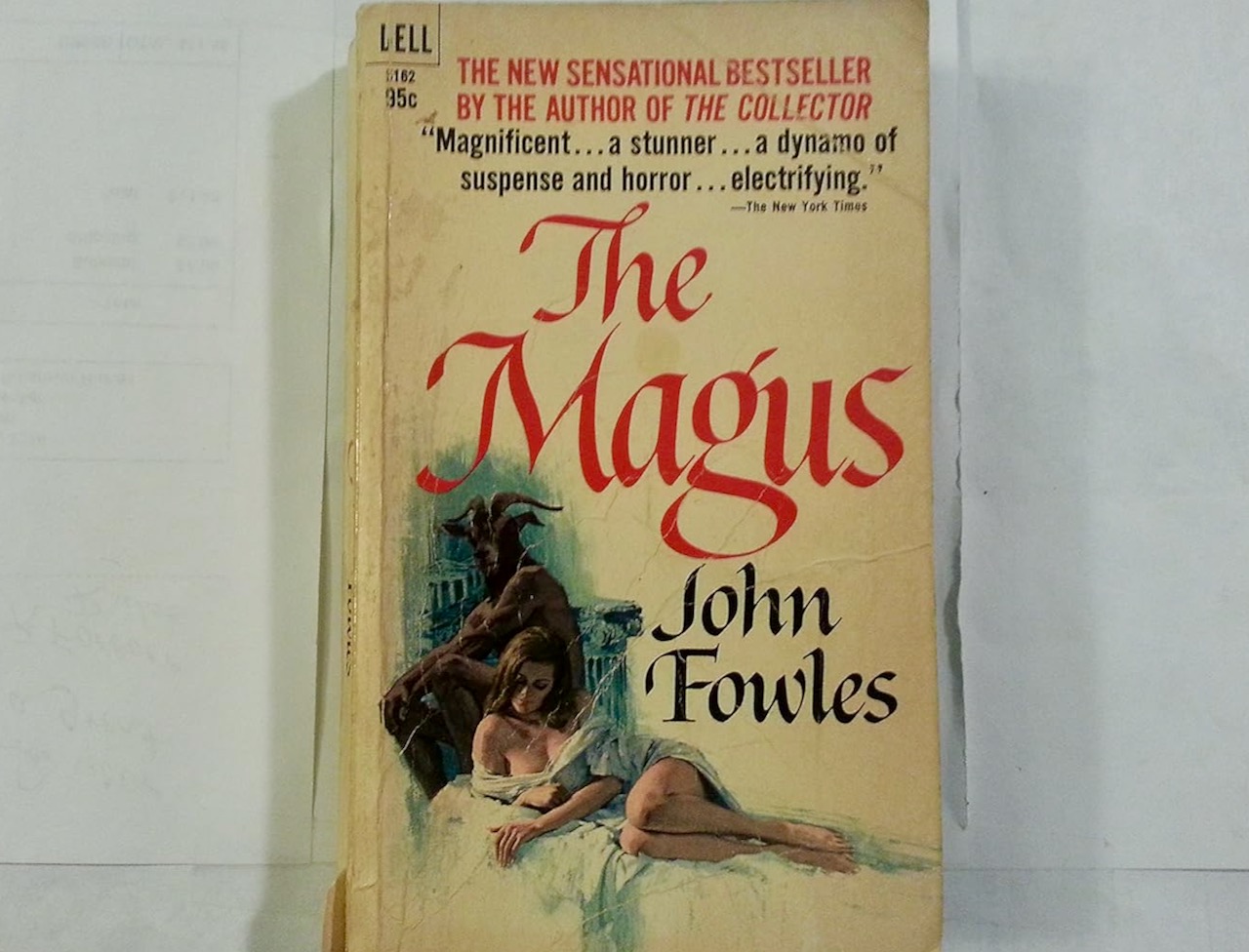

John Fowles was an acclaimed author whose novels, particularly the first three—The Collector (1963), The Magus (1965) and The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1969)—have been widely admired international best-sellers. In 2008, The Times named Fowles as number 30 in its list of the top 50 greatest British writers since 1945. The French Lieutenant’s Woman was ranked number 31 on Time magazine’s list of the 100 greatest novels since the periodical’s inception in 1923 and I was tempted to put it on my list: Indeed, had I chosen another Fowles novel, I could have gone my usual route and recommended a great film version you might want to see, since both The Collector and French Lieutenant’s Woman have been made into excellent films, most notably the latter, which featured admirable performances by Jeremy Irons and Meryl Streep and a strong screenplay by future Nobel Prize winner Harold Pinter. Alas, I chose instead The Magus. Now The Magus is considered by many to be Fowles’ best book, but the 1968 film version of the novel starring Michael Caine and Anthony Quinn was a complete disaster—even Caine said it was one of the worst films he’d ever been involved in.

Purchase Tramadol Visa So we won’t talk about the film any more. The novel was widely admired, especially for its metafictional post-modernism. It was included in the Modern Library list of the best English language novels of the 20th century, and was included as number 67 in the BBC-sponsored “Big Read” survey ranking the greatest British novels. And it comes in at number 36 on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English language.”

The Magus grew out of Fowles’ own experiences: After graduating from Oxford, he accepted an offer to become an English master at the Anargyrios and Korgialenios boarding school for boys on the Greek island of Spetses. He taught at the school from 1951 to 1953, at which point he and the other masters were all fired when they tried to institute reforms in the school. When he returned to England, Fowles began trying to write a novel based on his experiences at the school and on the Greek island, originally entitling the book “The Godgame.” It was the first novel he wrote, but the second to be published, since he finished The Collector before he felt The Magus was ready. He had worked on it for twelve years before finally publishing it in 1965—and even then, after it had been a critical success and a bestseller, he revised the book again and published the revised second edition in 1977.

The novel’s protagonist and narrator, Nicholas Urfe, recently graduated from Oxford, “handsomely equipped to fail” as he puts it, is teaching at a small school in Britain but longs to be a poet. He meets a young Australian woman, Alison Kelly, at a party in London and the two become close. But Nicholas begins to fear that Alison and he may be falling in love, and he’s not ready for that. He’s also coming to realize that he really isn’t going to be the next W.B. Yeats and is trying to come to grips with his own mediocrity. “The pattern of destiny seemed pretty clear,” he says at one point. “Down and down, and down.”

And so, bored and unfulfilled at the age of 26 he abandons Alison and accepts another post at the Lord Byron School on the (fictional) Greek island of Phraxos. All of this should sound familiar to you. On Phraxos, Jonathan again becomes disillusioned, lonely, and depressed, even to the point of contemplating suicide. But then, in the course of one of his solitary walks about Phraxos, Nicholas comes across the estate of Maurice Conchis, a wealthy Greek (though born in England). Conchis is a recluse who befriends Nicholas and, as their friendship slowly develops, Nicholas finds that Conchis may have been a Nazi collaborator during the German occupation of Greece in the war. And he is fond of using hypnotism and psychological games on his guests. At least Nicholas assumes they are games.

The mysterious and eccentric Conchis gradually draws Nicholas into his psychological diversions, which include eccentric costumed masques. These Nicholas comes to term the “godgame,” Fowles’ original title for the book. Nicholas thinks these are simply a joke, but as time goes on and he becomes, unbeknownst to himself, a performer in the masques; he also becomes enamored of a young woman and fellow performer in these enertainments, called Lily Montgomery, or Julie Holmes, or Vanessa Maxwell, who is a mysterious guest at the Conchis estate. Is she the dead lover of the host? Is she a mental patient? Is she an actress who is being forced to take part in these games? Caught up in the godgame, Nicholas begins to believe this is the special, magical life he had always been destined to live. In these new amusements, he is as special as he always thought he should be.

At one point, Nicholas reconnects with Alison on a trip to Athens, but after letting her go again he learns that she has committed suicide. Unless perhaps she didn’t. He also begins to realize that these elaborate reenactments of classical mythology and World War II are not so much the working out of Conchis’s psychological history as the magus Conchis’s playing with Nicholas’s own psyche. There are myriad twists and turns as Conchis and the novel move toward the end, and I won’t spoil these for anyone looking to read this book. I will say that the ending is frustrating, because Fowles gives the novel two possible outcomes, between which the readers themselves must determine. Or not.

The reader is as much a part of this wild ride as is Nicholas, and the lesson of the godgame is also brought home to us—and that lesson is uncertainty. Trapped in our own consciousness (it’s no coincidence that the magus’s name is Conchis) we may never be able to tell what is truth and what is feigned. Or maybe there is no difference. Maybe what we think simply becomes what is real for us. Maybe this is the point of the double ending. The question is not necessarily which one of the endings is true, but which one we decide to think is true.

Or maybe that’s not it at all. Nicholas’s thoughts and opinions about himself and his own self-worth were the illusions of youth, and by the book’s end he’s definitely been deceived. Perhaps there is a truth somewhere that we simply choose not to acknowledge. Perhaps the novel is a “godgame” for its readers. Perhaps all novels are. Anyway, this novel remains indeterminate and metafictional, an early and significant example of post-modern fiction. I recommend giving it a go—you’ll be glad you did.