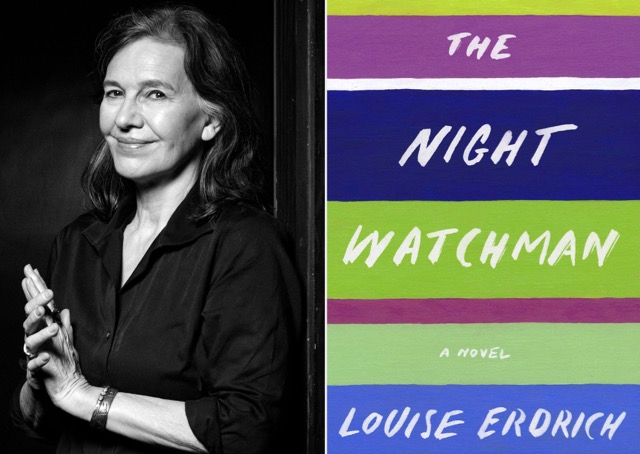

One of the most important writers of what’s generally considered the “second wave” of the Native American Renaissance, Louise Erdrich has been one of my favorite writers for more than forty years. Her first novel, Love Medicine, was an instant classic, winning the National Book Critics Circle Award in 1984—the only first novel ever to win that award. In 2009 her novel The Plague of Doves was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize, and in 2012 her novel The Round House won the National Book Award for fiction. A few years later, she won her second National Book Critics Circle Award for the novel LaRose. Her Pulitzer finally came with her 2020 novel, The Night Watchman. That novel appeared in March of that year, and my wife and I had the good luck of attending one of her first public readings from the novel that same month at the AWP conference in San Antonio—just days before COVID-19 shut everything down.

I knew I had to include Erdrich on my “100 Most Lovable Novels” list, but the question was which book to pick? I loved Love Medicine, and that was the most venerable choice, but The Round House and Plague of Doves were also favorites. But it’s the most recent book, and the 2021 Pulitzer Prize winner, that I finally landed on. It’s too recent to appear on many lists, but it does appear as number 66 in the Readers’ Digest list of “The Greatest Books of All Time,” and it is on The Center for Fiction’s list of “200 Books that Shaped 200 Years of Literature.”

I posted a review of this on my web site before it had won the Pulitzer, and Ironically I began writing it on June 25, the 144th anniversary of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, commonly known as “Custer’s Last Stand.” That battle was the culmination of the career of the cavalry commander responsible for the slaughter of hundreds of Native Americans, and his defeat became the excuse for the slaughter of hundreds more. That string of battles was sparked by the U.S. government’s seizure, in violation of their own treaty, of the Native Americans’ sacred Black Hills, and part of a larger series of wars whose undisguised intent was to eliminate any competition for the westward advancement of white Americans and the annihilation of anyone standing in the way of that expansion. Yet those pesky Indians kept preserving their traditions and ways of life after agreeing to treaties and retiring to their reservations. But it turns out that some of those reservations were on land that American corporations could profit from. And treaties? Well, they were made to be violated, weren’t they? Still, Indian wars looked bad, so new methods had to be developed. Thus the period from 1953 to 1968 is known, in the history of American Indian relations with the U.S. government, as the “Termination” period.

It began with a U.S. senator from Utah named Arthur V. Watkins, who was appointed chair of the Senate Interior Committee Subcommittee on Indian Affairs in 1947. A Mormon who associated Native Americans with the evil Lamanite tribe in the Book of Mormon, Watkins conceived of and pursued a policy aimed at terminating the special status of Indian tribes under U.S. law. In 1953, Watkins’ allies introduced a bill concurrently in the House and the Senate that was passed as House Concurrent Resolution 108. This law aimed to eliminate any laws that treated Native Americans differently from any other U.S. citizens; to eliminate the BIA; to end all federal supervision over individual Indians, Indian tribes, and their resources. Of course, it was those resources that were the chief target. Watkins compared his bill to the Emancipation Proclamation, saying it would “free” Indians and entitle them to “the same privileges and responsibilities as are applicable to other citizens of the United States.” In other words, it would force them to assimilate, and would wipe out their tribal identity, their identity as Indians. And of course it would nullify all promises made to Indian tribes when they signed their treaties. The bill became known as the “termination bill,” and it specified the first thirteen tribes to be terminated. Among these tribes were the Turtle Mountain Chippewa.

The Turtle Mountain band is Louise Erdrich’s mother’s tribe, and the writer’s maternal grandfather, Patrick Gourneau, was tribal chairman in the early 1950s, a period when he also worked as night watchman at a factory on the reservation. In 1953, in the wake of the passage of House Concurrent Resolution 108, Gourneau in his role as chairman traveled to Washington with other members of the band to testify before Congress in an attempt to stave off termination. That is the seed from which has grown Erdrich’s novel, The Night Watchman. Erdrich has changed the name of the protagonist to Thomas Wazhask, but has made no secret that Thomas is based very closely upon her grandfather.

The novel follows two separate but connected story arcs. The first, of course, is Thomas’s story, from the moment he learns of the infamous “termination bill,” through his working out what it really means for the tribe, to a meeting with BIA bureaucrats in Fargo, where one of his fellow tribesmen, a minor character named Eddy Mink, responds to the cessation of Federal monetary support for Indian people by saying, “The services that the government provides to Indians might be likened to rent. The rent for use of the entire country of the United States.” Thomas’s story culminates in the Turtle Mountain representatives’ testimony before Senator Watkins’ committee in the nation’s capital. Erdrich’s presentation of these events is carefully researched and presented in a restrained, straightforward manner, like bureaucratic Nazi memos about the Holocaust.

The other story arc in the novel concerns Thomas’s completely fictional niece Patrice Paranteau, whose friends often call her “Pixie,” a nickname she detests. Patrice has an alcoholic father who comes home occasionally and brings chaos to the peaceful home where Patrice lives with her mother, sister, and brother Pokey, and it is Patrice who supports the family, working in the jewel-bearing plant at which Thomas is night watchman. She takes a good deal of pride in being the best at the intricate work of laying jewels into keyboards to be used in watches. In a recent interview in Time magazine, Erdrich said, “The jewel-bearing plant is real and it still stands. It hired mostly women, and what an extraordinary thing. I was excited to write a book that had indigenous people doing factory work because you don’t read that.”

Patrice’s story arc has two strands. First, her sister Vera has left the reservation and gone to Minneapolis, where she has had a baby. But since then, her family has lost touch with her. Determined to discover what’s happened to Vera, Patrice borrows vacation days from her factory friends and takes time off to go to the Twin Cities to find her sister. Like most quests, her first venture off the reservation turns into a learning experience, in which her most memorable adventure is taking a job in a nightclub as an underwater dancer dressed in a rubber cow suit and billed as Babe, Paul Bunyan’s Blue Ox. But although in the cities Patrice is able to find a noir world of drugs and prostitution that her sister may have been involved in, she never is able to find Vera.

Her adventure does give her the confidence to accompany Thomas to Washington and be part of the group that testifies before Congress. Back home, though, Patrice is being wooed by two men: One is Wood Mountain, a Chippewa boxer her own age, and the other the older non-Indian math teacher and coach of Wood Mountain’s boxing team, Lloyd Barnes. Patrice isn’t sure she wants either one of them, and makes that pretty clear to Barnes. At this point she recalls some memorable advice from her mom:

And Patrice thought another thing her mother said was definitely true—you never really knew a man until you told him you didn’t love him. That’s when his true ugliness, submerged to charm you, might surface.

Wood Mountain actually goes to Minneapolis to find Patrice and help her if he can. He also becomes involved in Thomas’s story as the tribal chairman organizes a huge boxing match pitting Wood Mountain against his nemesis, the Anglo-champion Joe Wobleszynski, in order to raise money to send the Turtle Mountain delegation to Washington.

The two strands of the plot complement one another in more than overlapping events. Patrice’s odyssey demonstrates what Thomas and his delegation are bent on showing the politicians: These people are unique and valuable as Indians, and their reservation is a part of that character. To terminate them would be to terminate a way of being human that would not otherwise exist. We see this way of life through the actions of the characters, perhaps especially in their experiences of the natural world. Here is one small example:

The sun was low in the sky, casting slant regal light. As they plodded along, the golden radiance intensified until it seemed to emanate from every feature of the land. Trees, brush, snow, hills. She couldn’t stop looking. The road led past frozen sloughs that bristled with scorched reeds. Clutches of red willow burned. The fans and whips of branches glowed, alive. Winter clouds formed patterns against the fierce gray sky. Scales, looped ropes, the bones of fish. The world was tender with significance.

As the Turtle Mountain delegation prepares to travel to Washington, they seek the help of the daughter of one of the men of the tribe, who lives in Minneapolis with her white mother and has written an MA thesis on the economic circumstances of the Turtle Mountain Chippewa. She has the kind of information the politicians in Washington will respect, and her part in presenting evidence to the congressional committee becomes invaluable. Though the girl, Millie Cloud, is essentially an outsider, she reconnects with her Indian side partly in becoming close to Patrice as she travels with the group. Erdrich describes her conflicting emotions this way:

It was something about being an Indian. And the government. The government acted like Indians owed them something, but wasn’t it the other way around? She hadn’t been educated in a boarding school or educated in any way about Indians. From her Catholic schooling, she would never have known about Indians at all except as a bunch of heathens who were vanquished or conveniently died off. She’d hardly known her family and was as assimilated as an Indian could be. And people hardly ever recognized her as an Indian. So why did she firmly see herself as an Indian? Why did she value this? Why did she not long for the anonymity of whiteness, the ease of it, the pleasures of fitting in? When people found out why she looked a little different, they would often say, “I never thought of you as an Indian.” And it would be said as a compliment. But it felt more like an insult.

I certainly don’t want to spoil the plot of the book, so I won’t say more about it. I will say that this is a novel into which Erdrich has poured all the narrative skills she’s shown in previous novels from Love Medicine through Plague of Doves and The Round House, creating a world in which readers can become absorbed and in which we meet characters we know well enough to think of as real. From the factory to the boxing ring to the underwater dancing, we believe we are in this world, and when magical realist aspects occur, like Thomas’s conversations with his long-dead boyhood friend Roderick, or even the mystical vision he experiences when he thinks he is freezing to death—a vision of angelic spirits “filmy and brightly indistinct” in the sky, Jesus Christ among them, who “looked just like the others”—they seem events as acceptable as anything else.

In her Afterword to the book, Erdrich notes that “In all, 113 tribal nations suffered the disaster of termination; 1.4 million acres of tribal land was lost. Wealth flowed to private corporations, while many people in terminated tribes died early, in poverty. Not one tribe profited.” The novel celebrates the heroic and successful quest of one tribe to stave off termination. But we are reminded of the many who were not so successful, and to celebrate those ways of being human that such terminations may have rendered extinct,