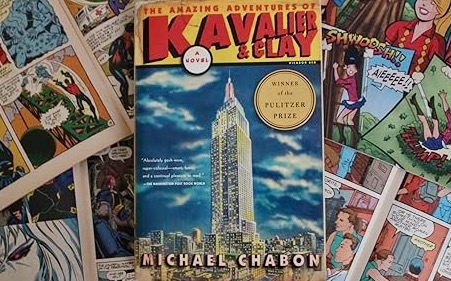

I must admit once again that it took me way too long—fifteen years, I reckon—to finally read Michael Chabon’s brilliant tour-de-force, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay. But I freely admit that once I did I was so astonished by every aspect of the novel that I resolved there and then to become a Chabon completist, and to read everything Chabon has written, at least as far as his fiction goes. And I want to say that, having accomplished that particular feat, none of it disappoints, and I was especially enamored of The Yiddish Policeman’s Union, which I recommend highly. But if I have to choose one novel to represent Chabon on this list (and I do have to, having set the rule for myself), it has to be Chabon’s 2001 Pulitzer-Prize-winning Kavalier & Clay. The novel was ranked as #3 in Entertainment Weekly’s “Best Books of the Decade” in 2009, and later, in The Guardian’s 2019 list of the “100 Best Books of the 21st century, The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay was ranked (far too low) as #57. For me, the novel comes in as #17 (alphabetically) on my list of the “100 Most Loveable Novels in the English Language.”

The novel depicts the lives and adventures of two Jewish cousins. One is Sammy Klayman, a 17-year old Brooklyn-born would-be writer and entrepreneur. The novel begins when a Greyhound bus carrying Sammy’s cousin, 19-year-old Josef “Joe” Kavalier arrives in New York, and Joe comes to live with Sammy’s family. Joe, a gifted artist as well as a trained magician and “escape artist,” has, with the help of his magician mentor Kornblum, just pulled off his greatest Houdini-like escape: He has escaped from Nazi-occupied Prague into temporarily free Lithuania by hiding in a coffin that he shares with the Golem of Prague. Joe has made his way to Japan, then San Francisco, and thence to New York. And here, sharing a room with Sammy, Joe talks about making money fast in order to help the rest of his family get out of Prague.

Sammy recognizes Joe’s artistic talent, and gets him a job at the Empire Novelty company where he works. But the newest novelty for American youth is the new comic book craze, set off by the spectacular debut of Superman. Thinking to cash in on the latest fad and funded by the novelty company’s owner Sheldon Anapol, Sammy begins writing adventure stories under the name “Sam Clay,” stories which Joe illustrates. They have huge success with their super-hero character the Escapist, who seems to be a cross between Batman, Captain America, and Joe’s childhood idol Harry Houdini. Part of the Escapist’s success is his anti-Fascist leanings, and on one classic comic book cover, he is shown punching Hitler in the face (an allusion to the actual cover of the first issue of Captain America).

Joe and Sammy are so enthusiastic about their creation that they don’t notice for some time that their creative talents are being exploited by their employer, who’s getting rich on their creative talents. Meanwhile Joe has met another artist, Rosa Saks, with whom he begins a love affair, and who becomes the inspiration for a new comic book superhero in Joe’s repertoire, the creature of the night Luna Moth. Meanwhile Sammy is in love with the actor hired to play the Escapist on film, and struggles mightily with his own sexuality. After an unlooked for tragedy, Joe joins the navy to fight the Nazis and breaks up the creative team, leaving Sammy and Rosa to deal with their own difficulties.

Any further discussion of the plot will reveal too many spoilers in this sweeping, epic story, and I hope you will read it yourself to experience the many surprising twists. If you have any interest in the history of comic books—if you’re a fan of the Marvel universe or more of a Superman-Batman-Wonder Woman type—you will love this novel. The story spans fifteen years, roughly the time frame of what is known as the “Golden Age” of comics, from the premier of Superman to the Estes Kefauver Senate hearings of 1954, which were formed to examine the phenomenon of juvenile delinquency in America, and focused on comic books as a major cause (and which, in the novel, have a devastating effect on the Kavalier and Clay partnership).

The theme that runs through The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay, from beginning to end (as many readers have noted) is the idea of escape. It’s quite true that comic books to a large extent are escapist, that people read them to escape from the real world into a world where superheroes can solve every problem and good will always triumph. But is this a bad thing? J.R.R. Tolkien said the same thing about what he called “Fairy-Stories,” and defended the “escapism” therein:

“I have claimed that Escape is one of the main functions of fairy-stories, and since I do not disapprove of them, it is plain that I do not accept the tone of scorn or pity with which ‘Escape’ is now so often used: …. confusing, not always by sincere error, the Escape of the Prisoner with the Flight of the Deserter. Just so a Party-spokesman might have labelled departure from the misery of the Führer’s or any other Reich and even criticism of it as treachery. …Not only do they confound the escape of the prisoner with the flight of the deserter; but they would seem to prefer the acquiescence of the ‘quisling’ to the resistance of the patriot.”

The “escapes” in Kavalier and Clay are all of the sort that Tolkien supports. Joe’s escape from Nazi-occupied Prague is the first such escape. “The Escapist” is a character who, like Houdini, uses his powers to escape from bonds which tie him and others down—in his case the bonds of tyranny. Sammy struggles to escape from his own sexuality, or, alternately, the constraints that society places upon his sexuality. And Joe tries to escape from the horrors and devastation of his own past traumas. In words that almost echo Tolkien’s, Chabon has Joe decide

“Having lost his mother, father, brother, and grandfather, the friends and foes of his youth, his beloved teacher Bernard Kornblum, his city, his history—his home—the usual charge leveled against comic books, that they offered merely an escape from reality, seemed to Joe actually to be a powerful argument on their behalf…”

And I might add, a powerful argument on the novel’s behalf. If you’ve not read this one, you seriously ought to give it a look. You’ll be glad you did.