[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/SusannTennyson.jpg’ attachment=313′ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Ruud Rating

Elvis and Nixon

Two Susanns/Half Tenneyson[/av_image]

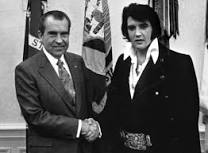

A small and quirky movie likely to get lost among the dazzling superhero and CGI orgy of summer blockbusters, Liza Johnson’s Elvis & Nixon is a bright kernel of fun that you might want to take in if you have a chance. The film, billed as “the untold true story behind the meeting of the King of Rock ’n Roll and President Nixon,” immortalized by the famous photograph from December 1970 of Nixon shaking hands with Elvis at the White House (which is the most requested image in the U.S. National Archives), takes a stab at the “untold” story, but is only “true” by a generous definition of the term. Yes, it is a fact that on a morning shortly before Christmas in 1970, Elvis Presley appeared unannounced at the entrance to the White House, asking to see President Richard Nixon. And yes, it is true that the purpose of his visit was an apparently sincere request that the president make him a “federal agent at large.” And yes, it is true that Nixon ultimately agreed to meet with the King, and that a meeting took place, immortalized in the famous photograph. But the details behind that request, and most notably what exactly took place in that meeting between those two famous and, shall we say, eccentric icons, is unknown and thus the body of the film complete conjecture. But it is interesting and in many ways persuasive conjecture, and if it didn’t happen exactly this way, there’s no reason to believe it couldn’t have.

One thing that the film does not do is deal seriously with the issues that sparked this strange meeting. Johnson and her writing team, composed of Joey Sagal, Hanala Stadner and Princess Bride actor Cary Elwes, are, for the most part, just a little too young to actually remember 1970 and the turmoil that surrounded the president and his policies: At the end of April, for example, in the wake of Nixon’s invasion of neutral Cambodia, protests were ignited on college campuses across the country. After Nixon called the protestors “bums” in a speech, the protests heated up, culminating at Kent State on May 4, when the Ohio National Guard shot and killed four students, two of whom were not a part of the protest. On May 8, 100,000 protestors marched in Washington and another 150,000 in San Francisco, violent confrontations followed in 16 states while some four million students were involved in protests at 450 colleges nationwide. Congress responded with the Church-Cooper amendment, which ultimately passed on December 22—the day after Elvis met with Nixon. In effect, that act reversed the Gulf of Tonkin resolution of 1964, under the auspices of which Nixon and his predecessor Lyndon Johnson had waged the Vietnam War. And in December, Elvis went to the White House.

A film interested in exploring seriously the historical context of that bizarre meeting might have made some of this history available at least by allusion. This one does not. We see Elvis shoot a TV set in his home in Graceland when news of protests come on, but since Elvis is just old enough to be beyond the college-age protests, and since he served proudly in the armed forces himself, and since Nixon is of an older generation of world War II veterans who believe that the U.S. must always be on the right side of any conflict, we as an audience are not allowed to see any considered evaluation of what is going on outside the walls of Graceland and the White House.

As for Elvis, he was 35 in 1970, and riding the crest of a significant comeback. Having devoted most of the 1960s to making largely forgettable Hollywood movies and recording only the critically savaged soundtracks for those films, he had broken from all that in 1968 with a highly successful live television special that reconnected him with his roots and with popular music trends of the day. He sold out concerts in the Houston Astrodome and in Las Vegas, and subsequently charted top ten hits with “In the Ghetto” and “Suspicious Minds.” But by 1970, his album That’s the Way It Is revealed a shift from country and R & B to a very white pop style, appropriate for the Vegas crowd. At 35, Elvis was becoming irrelevant to the current music scene. In fact, it is notable that the film has a memorable soundtrack, featuring a number of hit songs from 1970 (or so) by such artists as Creedence Clearwater Revival, Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and Blood, Sweat, and Tears, but there isn’t a single Elvis song in it—a way of underscoring, perhaps, his irrelevance to cutting-edge rock music of the time.

So what we have, essentially, in the meeting of these two towering public figures, is the meeting of a pop icon who may recognize himself sliding into irrelevance, and a political animal beginning to feel the pressures of widespread opposition to his policies. They have a common enemy: the counterculture personified by drugs, hippie, and the Beatles, whom Elvis particularly disdains, chiefly because of John Lennon’s vocal and “Anti-American” opposition to the war. Both are surrounded by people who essentially tell them what they want to hear, and both are on the brink of fairly extreme retreats into their private worlds—Elvis ultimately retreating from celebrity into the sanctity of Graceland, an embattled Nixon ultimately into a fortified White House in the wake of post-Watergate calls for impeachment. The film could have delved into some serious psychological drama, but chooses a much lighter touch.

There are a few scenes of Elvis with a mirror: In one he opens up to film editor Jerry Schilling (Alex Pettyfer)—perhaps his only real friend, but one whose patience he spends the movie stretching—about how everybody simply sees him as a commodity, a “thing”; in another, he is rehearsing what to say to President Nixon when he meets him, and seems to wax sincere when he talks about his twin brother who died in infancy, and how perhaps he has accordingly been granted the luck and grace intended for both. Much more of this might have seemed heavy-handed. But there is even a scene in which the president opens up briefly to his aides about how he was not born with any kind of natural good looks or appeal, and has had to struggle harder to make something of himself—in some ways the opposite of Elvis’s revelation. Yet both men are deeply insecure, a shared characteristic that ultimately seems to give them a bonding moment.

But essentially Johnson plays the story for its comic potential, and the offbeat absurdity of the whole situation. The movie follows what facts are available. Much of the humor occurs in the trip to Washington—in the airport, an Elvis impersonator (a cameo appearance by the screenwriter Joey Sagal) tells the real Elvis that he isn’t bad, but Elvis would never actually wear what he’s wearing. There’s a good deal of humor too in the behind-the-scenes maneuvering to convince the president to accept the meeting (Elvis will bring him a lot of votes, his aides are convinced, but even that doesn’t persuade Nixon)—until Nixon’s daughter Julia calls him and insists he take the meeting so that he can get an autographed picture of the King (this may be the writers’ invention, but it does allow Nixon to show a very human side, taking the meeting not for any political advantage but to make his daughter happy). When Elvis autographs the picture for Julie in the President’s office, he asks Nixon, “What about the other one? She doesn’t like me?” Nixon shrugs and answers that she’s a Beach Boys’ fan. “Ah,” the King answers. “Good Vibrations.”

Thus Elvis and his aides are able to orchestrate a meeting with the President on December 21, 1970, during which Elvis expresses his loyalty and patriotism, his disdain for the “Hippie” counterculture and its vocal opposition to the war, and particularly its drug culture (much of which he sees embodied in the Beatles and their fans). And he asks Nixon for a “special Federal Agent” badge from the Bureau of Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs—not, as the president and his aides at first believe, just as a souvenir, but so that he can seriously work as an undercover drug agent within the entertainment community. There is a moment of silence when Nixon himself realizes how out of touch with reality Elvis is. But not so out of touch that they can’t have a meaningful conversation in which they bond over their mutual interests in American values, Dr. Pepper, M&Ms and guns.

Spacey is brilliant in his ability to humanize Nixon, while still making him recognizable—somewhat too close to Spacey’s Machiavellian Frank Underwood (from House of Cards) for comfort. Colin Hanks (TV’s Fargo) and Alex Pettyfer (Lee Daniels’ The Butler) are notable in supporting roles as they try to make this meeting happen. But mostly it is Shannon’s movie, and though there is little real physical resemblance between him and the King, he manages to embody Presley’s mannerisms and, convincingly, his paranoias as well in a remarkably believable performance.

What we have in the end is a diverting and well-acted film that is interesting and entertaining enough, but that could have been much more. It misses the opportunity to explore historical events as a comment on current affairs, and it chooses not to delve deeply into the psychological motivations of two of the twentieth century’s most enigmatic figures. I’ll give it two Jacqueline Susanns and half a Tennyson.