If you grew up reading and/or watching tales of the great medieval outlaw hero Robin Hood robbing from the rich and giving to the poor, you probably dreamt of visiting Nottingham and Sherwood Forest. I knew I did. I watched the Richard Greene The Adventures of Robin Hood TV series (1955-59) when I was quite young (“Robin Hood, Robin Hood, Riding through the glen,/ Robin Hood, Robin Hood, with his band of men”), and saw the famous 1938 Errol Flynn version of The Adventures of Robin Hood replayed on TV when I was a bit older. And then of course here was Howard Pyles’ famous 1883 novel for boys, The Merry Adventures of Robin Hood, the most influential Robin Hood novel of all time and the book that, I suppose, made us refer to his men as “merry.” So I’ve always wanted to visit Nottingham (where Robin’s arch-enemy was sheriff).

But if you think you’re going to go there and see a lot of sights related to the historical Robin Hood, you’ve got another think coming. There ain’t no such person, Never was. The legendary Robin Hood is historical only in the sense that he personifies a spirit of independence among the common people of later medieval England, a kind of resentment of the rich nobles and prelates to whom Robin gives their come-uppance.

Robin’s first appearance in recorded history comes in William Langland’s poem Piers Plowman around 1377. There, he’s the subject of stories the allegorical character of Sloth likes to hear while hanging around the tavern. The ballads of Robin Hood were composed by popular minstrels and storytellers for the common folk, often in a rough-and-tumble comic vein. There are no great Robin Hood epic poems and no Sir Thomas Malory to compile the Robin Hood story into a single long and complex narrative. What survive are many shorter ballads that would serve as brief entertainments, plus one long (1824-line) 15th century poem in ballad stanzas, the Gest of Robin Hood, comprising seven loosely connected “fits” telling stories of Robin and Little John.

These ballads record separate instances and tell Robin’s story in fragments. In the 18th century, these fragments were collected, first in Thomas Percy’s Reliques of Ancient English Poetry in 1765, then more completely in Joseph Ritson’s Robin Hood collection in 1795 (complete with a fictional “biography” of the outlaw). In the following century, the most definitive collection of Robin Hood ballads was included by Francis James Child in The English and Scottish Popular Ballads (volume III). For today’s common reader, a comprehensive collection of Robin Hood ballads is readily available in Robin Hood and Other Outlaw Tales, edited by Stephen Knight and Thomas Ohlgren (1997), to which I refer anyone who’d like to read these texts first hand.

The 1938 film marks perhaps the starting point for contemporary versions of the Robin Hood legend. The film shows the outlaw hero as a disgraced nobleman, Robin of Locksley, who remains loyal to the absent crusading King Richard the Lionhearted against the machinations of his usurping brother Prince John and his allies, Sir Guy of Gisbourne and the Sheriff of Nottingham. In the original ballad tradition, though, Robin is pure English yeoman stock, definitely no nobleman, and delights in robbing those of aristocratic rank and in flouting the authorities who enforce the status quo. But an Elizabethan dramatist named Antony Munday wrote two plays, The Downfall of Robert, Earl of Huntington and The Death of Robert, Earl of Huntington, which rewrote Robin’s story and made him a fallen nobleman, and that is reinforced in the film version.

Secondly, the placement of Robin into the historical period from 1189 to 1199, the reign of Richard I, is the brainchild of Sir Walter Scott, who includes Robin Hood and his men in his novel Ivanhoe, set during that time. In the ballads, specific dates are rarely given, though the early ones seem to reflect a time roughly in the thirteenth or early fourteenth century. The fifteenth-century Gest mentions the good King Edward, but never specifies whether this is Edward I, Edward II or Edward III, which means it could be referring to any time between 1271 and 1377.

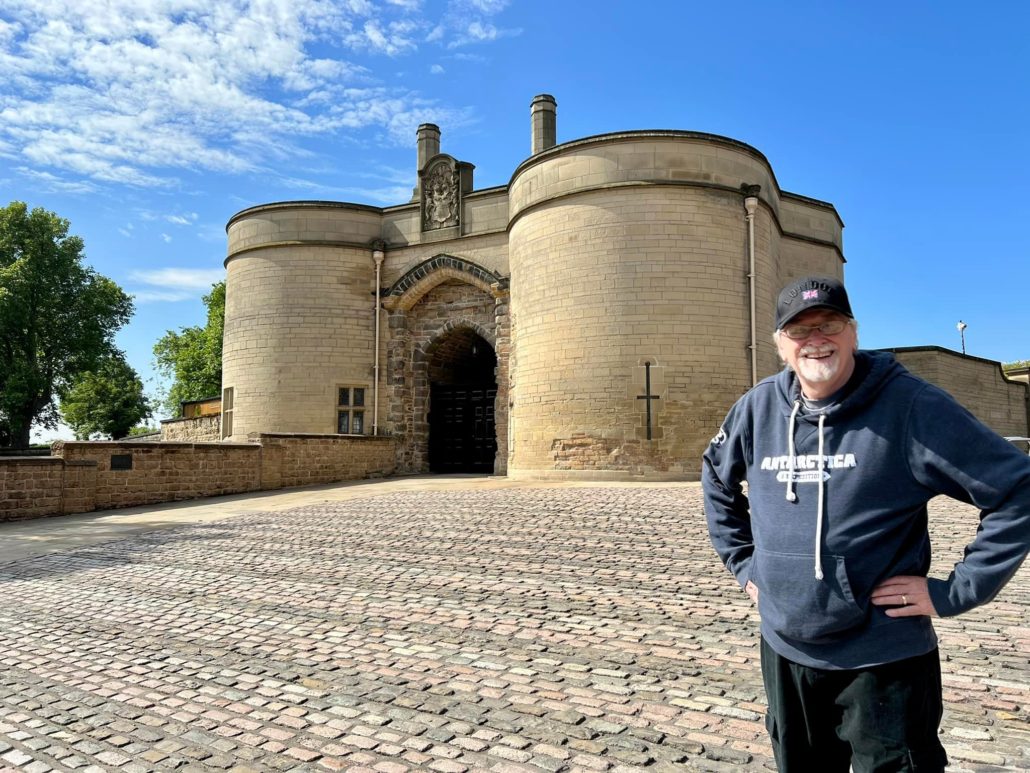

That is, he would have existed then if he’d existed at all. But don’t let any of that deter you from visiting Nottingham and Sherwood Forest. Obviously, this is the area of the country most associated with the legend. Some ballads place him farther north, around Barnesdale. But the Sheriff of Nottingham is always the enemy. In Nottingham, you’ll probably want to visit Nottingham Castle (better if you book in advance online—£13, or £12 for old guys like me—and £5 extra for the cave tours). The castle is not actually there—it was destroyed by Cromwell in the 17th century—but there is a large mansion there with a museum that tells a great deal about Nottingham, especially as a hotbed of rebellious activities over the years. There are a few Robin Hood related things that go on, but they’re mainly for kids. Don’t miss the cave tour if you go, though. There are miles of man-made caves and tunnels under Nottingham Castle—under much of the city, actually—and these have legitimate medieval associations, especially with Roger Mortimer (1st Earl of March), paramour of Queen Isabella, who holed up in the castle after overthrowing Isabella’s husband, King Edward II, until they were overthrown by Edward III in 1330. Mortimer is said to have hidden in one of these caves. For the romantics among you, there are legends that Robin Hood escaped from the sheriff’s prison through these tunnels.

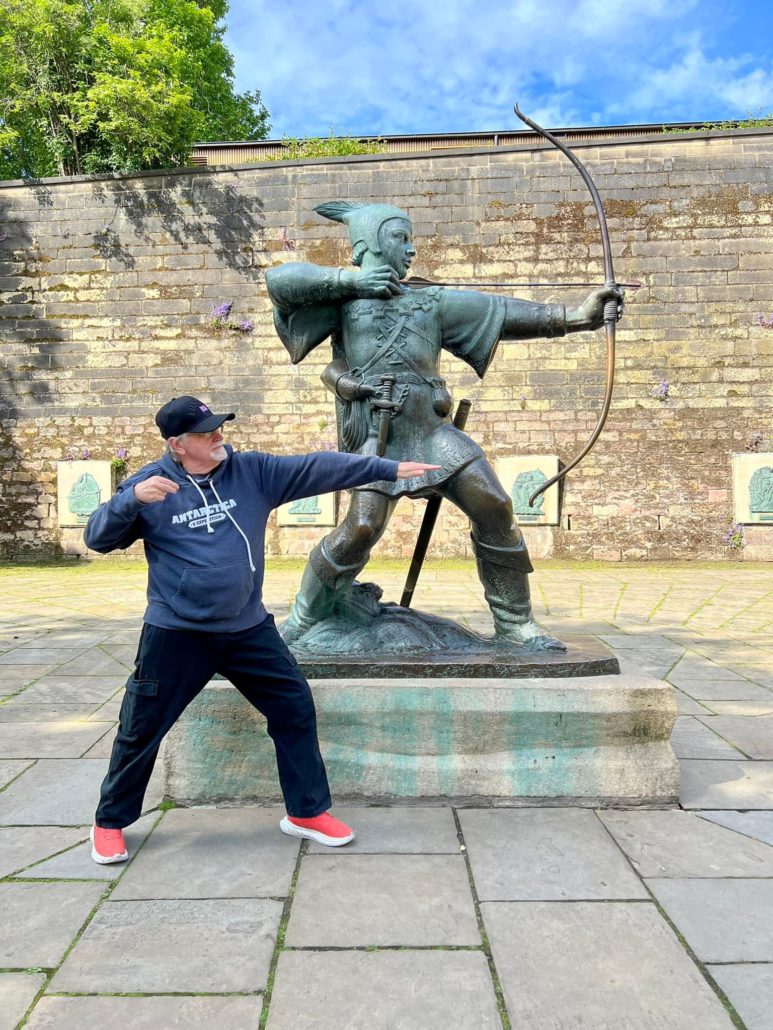

There is a famous seven-foot bronze statue of Robin Hood in front of the castle (as well as a few smaller pieces), sculpted by Royal Academy sculptor James Woodford. Also if you go, you may want to have a mild repast at the Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem pub just outside the castle wall. Claiming to be the oldest pub in Britain, it supposedly was where crusaders stopped before joining Richard I on the Third Crusade in 1189. Maybe Robin and his men ate there or had a pint.

Sherwood Forest, though, is a little more of a challenge to explore. But you can actually get there easily from the Victoria Bus Station (bay No. 9) on a special bus called the Sherwood Arrow (just a couple of pounds round trip, and you can pay the driver). It takes less than half an hour to get to the Visitors’ Centre, from which you can get information about the trails through the forest, all for free. You’ll want to walk to the Major Oak—a gigantic oak tree that is about a thousand years old and is reputed to have been the tree Robin and his men met under while hiding in the forest. And they probably would have, had they been real.

We were adventurous, and I had a notion to visit the newly discovered archeological site called Thinghowe in the Birklands area of Sherwood. It was a meeting place, a “Thing,” for the Danish settlers of this area of England back in the 10th century or so. It’s not on any of the maps available at the Visitors’ Centre, but you can find it on Google maps about a mile and a half beyond the Major Oak if you want to try to find it. But it’s a bit disappointing when you get there in that it’s so overgrown with tall weeds you can’t really walk around on the site very easily, and it’s hard to see any of the ancient stones that marked the meeting place. Also, beware of the time: You want to get back to the bus stop before the last bus stops here to take you back to Nottingham at 4:18 p.m. We made it two minutes early.

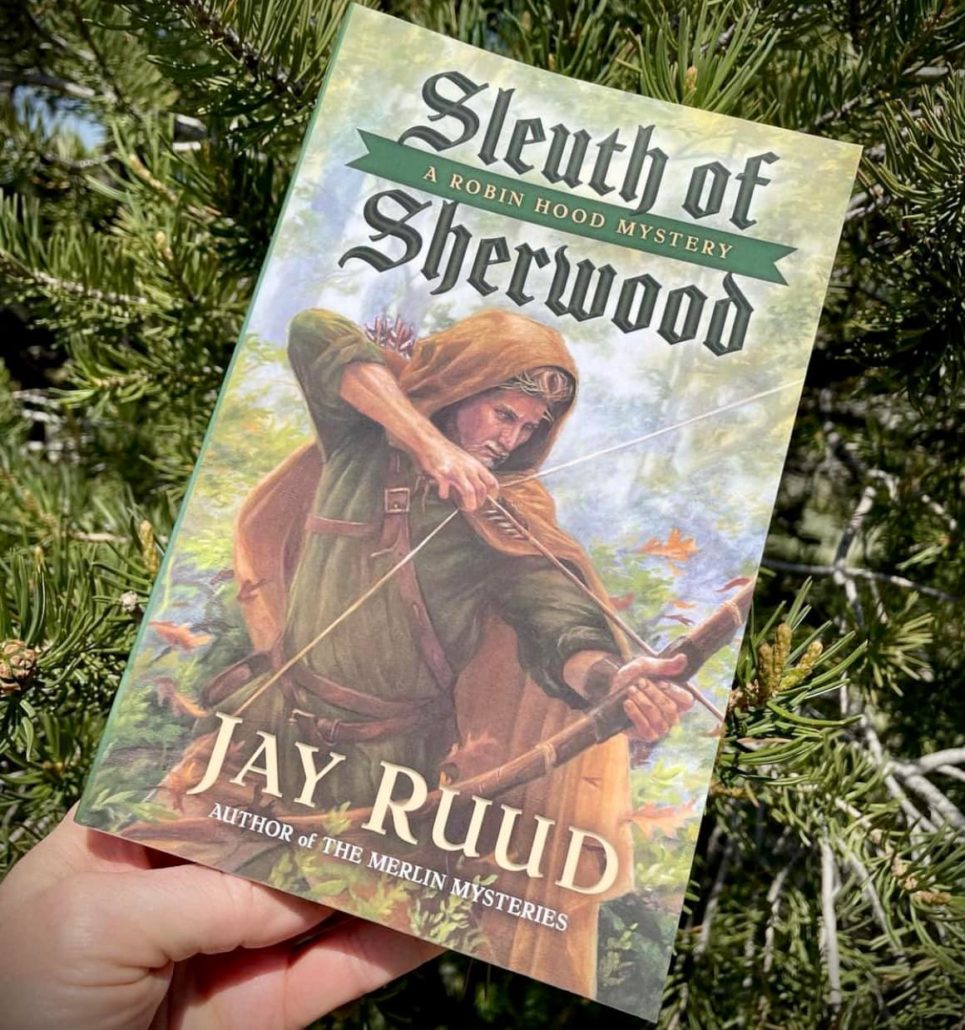

There are other fascinating sites for the literary traveler in Nottingham. The birthplace of D.H. Lawrence is here. So is Newstead Abbey, an Augustinian Abbey founded by Henry II in 1170 as penance for the murder of Thomas Beckett (so it’s an abbey Robin Hood would have known if he’d been real). After the dissolution of the monasteries under Henry VIII in the 16th century, the abbey became a private home, and was the ancestral home of Lord Byron, who lived here for a time. Unfortunately, I can’t tell you anything about Lawrence or Byron from these sites, since both of them were closed the day we wanted to see them. So my advice to you is, if you’re coming to Nottingham for the literary sites, check well in advance to see what’s open when! But definitely worth a stop on your tour of England. And of special interest to me because of my new Robin Hood mystery series, the first volume of which has just been published on June 15: