Order Tramadol 100Mg Online Sir Pelham Grenville (P.G.) Wodehouse was one of the most prolific (and consistently funny) writers in British history. From his first “school story” novel The Pothunters (1902) to his posthumously published final completed novel Aunts Aren’t Gentlemen (1974), Wodehouse published a total of 71 novels and 24 collections of short stories—95 fiction books in all. That’s a staggering number in itself, but add to that the 42 plays (many of them musicals, on which he collaborated most often with Guy Bolton and occasionally Jerome Kern—and most famously with Cole Porter on Anything Goes) and 15 film scripts he wrote in his first few decades as a writer, plus his three autobiographies and two volumes of letters, and you have an output virtually unmatched in in the history of English letters.

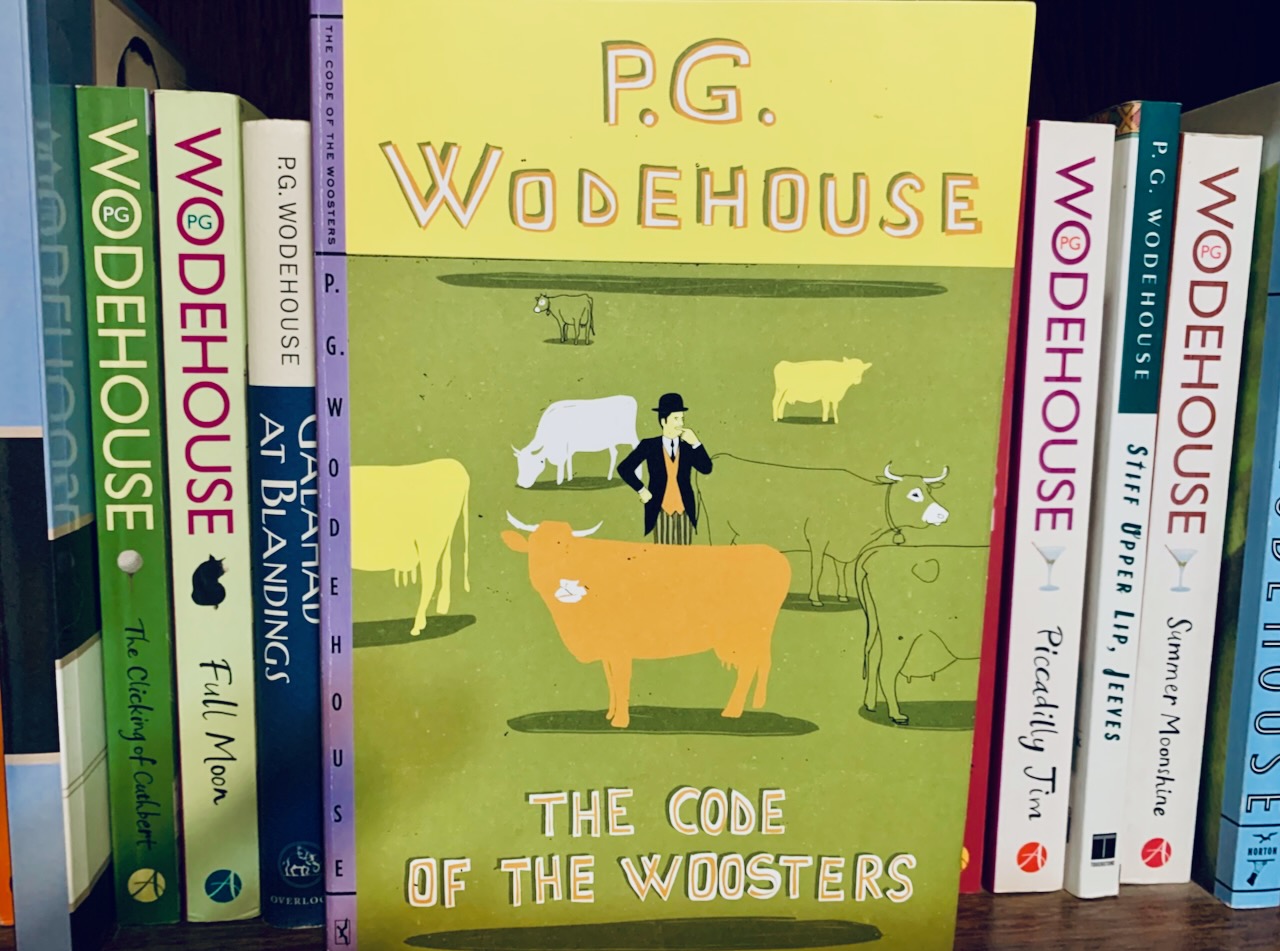

Cheap Tramadol Overnight Cod Justly famous for his comic novels, Wodehouse loved moving among several favorite series: there are 15 “Blandings Castle” novels, for example. There are four “Psmith” novels, five “Uncle Fred” novels, and seven “Ukridge” novels. But by far Wodehouse’s most popular and most acclaimed books are his 18 novels featuring Bertie Wooster and his butler/savior figure, the inimitable Jeeves. These novels are so consistently fine that many of them are reader favorites. One might mention Right Ho, Jeeves (1934), Joy in the Morning (1946), and Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (1956) for example. But the quintessential Jeeves novel that is most widely loved is probably The Code of the Woosters. Again, as is the case with Douglas Adams or with Terry Pratchett, purely comic masterpieces are less likely to appear on “Greatest Books” lists, but a surprising number of them do include The Code of the Woosters. On the BBC’s 2015 list of “The 100 Greatest British Novels,” Wodehouse’s book comes in at number 100 (there were actually 104 on the list). It also appears on The Daily Mail’s unnumbered rival list from 2019 called “A Hundred Novels to Change Your Life,” and on the Sunday Times’ 2013 list of “100 Books to Love.” On Penguin Classics’ famous 2022 list of “100 Must-Read Classics” as chosen by their readers, The Code of the Woosterscame in as number 26; on The Telegraph’s list of “100 Novels Everyone Should Read” from 2009 it was listed as number 15; and in a 2014 list compiled by two staff writers of the online journal CounterPunch called “100 Best Novels in English Since 1900,” Wodehouse’s book came in a number 14. It is included in Esquire magazine’s 2018 list of “The 30 Funniest Books Ever Written” and on The Telegraph’s 2014 list of “The 15 Best Comedy Books of All Time.” And of course, it appears here as number 99 (alphabetically) on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

If you’re paying attention, you probably noticed that almost all of the aforementioned lists are British. This might indicate that fewer American readers than English ones are familiar with Wodehouse’s work. So let me begin by talking about what exactly is so loveable about Wodehouse in general and this novel in particular. In a comedy, the first thing that generally comes to mind is the plot. The plot in fact is what defines the work as a comedy: a comedy begins with some kind of obstacle that threatens the happiness or success of the main character or characters, which must be overcome for a happy ending to occur. In the most typical comedies, there is a young couple who want to marry or to get together. They represent the “new society” who will bring on the happy ending. But they are prevented by a blocking figure, often in the form of the lady’s father or guardian who must be thwarted for the couple to succeed and bring on the better, “new” society in the end. Other characters tend to be aligned with one side or the other—with the blocking figure or with the “new society” as helping figures. Wodehouse’s plots tend to be quite involved and even frenetic, like the screwball comedies he had a hand in creating on stage or film.

In The Code of the Woosters, the protagonist Bertie Wooster is, as usual, a helping figure in the courtship of two of his old school pals Gussie Fink-Nottle (engaged, off and on, to the dramatic and sentimental Madeline Bassett), and the hapless curate Harold “Stinker” Pinker (hoping to marry the brash Stephanie “Stiffy” Byng). Both sets of lovers are on-again-off-again, mainly because of the chief blocking figure, Sir Watkyn Bassett, owner of a great country house called Totleigh Towers, who happens to be Madeline’s father and Stiffy’s uncle, and who is not ready to consent to either marriage. He is assisted by his very large and muscular friend Roderick Spode and by the local Constable Oates, who has a particular vendetta against Stiffy because her dog likes to attack policemen. Bertie, on the other hand, is aided by his Aunt Dahlia and by the one person who is never at a loss no matter what the difficulty, his gentleman’s gentleman Jeeves.

The plot is further complicated because Aunt Dahlia wants Bertie to steal Sir Bassett’s valuable 18th-century silver cow-creamer for her husband, who is also a collector, so that he will be in a good mood and help fund her ladies’ magazine. But Stiffy also wants him to steal the item so that Harold can catch him in the act and so ingratiate himself with Sir Watkyn. But Bertie wants nothing to do with the cow-creamer, because Sir Bassett happens to be the local magistrate and a few years past found Bertie guilty of stealing a policeman’s helmet and fined him five pounds, but threatens time in jail if there is another similar offense. The plot progresses as Bertie and Jeeves play a frenetic game of “Whac-a-Mole” as they solve one problem only to have another pop up immediately in another part of the house.

But beyond the convoluted plot, Wodehouse always creates a kind of comfortable nostalgic setting, taking us back to an England of wealthy gentry, fancy drawing rooms, and silly blokes with lots more money than brains and valets who hold everything together. It’s a somewhat idealized vision of the 1920s and 30s, which Wodehouse maintains even when he’s writing in the 60s. Here is a different kind of escapism than we’ve seen in fantasy, for example. Even in 1938, when he wrote this novel, with the Fascist threat looming, Wodehouse still provides the ideal of “peace in our time.” This is particularly significant in the character of Basset’s ally Roderick Spode. Spode is described as an “amateur dictator” who leads a fictional group of British fascists called the ”Saviours of Britain,” known colloquially as the “Black Shorts.” Spode is, as you might expect, a bully, first introduced in the novel thus:

About seven feet in height, and swathed in a plaid ulster which made him look about six feet across, he caught the eye and arrested it. It was as if Nature had intended to make a gorilla, and had changed its mind at the last moment.

Wodehouse’s readers at the time would have immediately recognized in Spode Wodehouse’s satire of Sir Oswald Mosley, the contemporary British leader of the British Union of Fascists (or “Blackshirts”). Wodehouse’s answer to the threat of fascism is ridicule—Spode’s threat is neutralized by the discovery that he designs women’s underclothing in his spare time. But that’s as far as Wodehouse is prepared to go—even his political satire is gently humorous.

But let’s get real: the chief reason Wodehouse is lovable goes beyond plot, setting, or characterization. It’s his language. It’s that unmistakable voice of the upper class twit that fills the pages that our protagonist Bertie narrates. Wodehouse has a genius for creating a conversational tone that is still never the conventional way of saying anything.

One if his little tricks is shortening words, especially when he’s saying something mundane or even cliché, as in “The gravity of the situash had at last impressed itself on her,” where situash is substituted for situation—a word that inevitably follows the expression “The gravity of…” Other times he doesn’t even abbreviate the word, but substitutes a single letter, as in a “quaver in the v.” (i.e., voice) or “turned on the h.” (i.e., heel)

Often his humorous phraseology is a parody of some high literary stylistic flourish, a kind of reductio ad absurdum of serious literary techniques. One of his favorite devices is the transferred epithet—transferring an adjective that describes one noun in a sentence to another related noun, as George Herbert does when he describes the “ragged noise and mirth / of thieves and murderers” (the noise isn’t ragged, the thieves and murderers are) or as Thomas Gray does when he tells us “The plowman homeward plods his weary way” (the way is not weary, the plowman is). Wodehouse loves to use such epithets for comic effect: at one point Stiffy “massages [her] dog’s spine with a pensive foot.” Elsewhere, Bertie says “I lighted a feverish cigarette.” A feverish cigarette or a pensive foot conjure up images far more absurd than a weary way or a ragged noise.

Another of Wodehouse’s favorite devices is the comic use of literary and biblical allusions. But again, when Melville’s Captain Ahab alludes to Milton’s fallen angel, declaring himself “proud as Lucifer” and “damned in the midst of paradise,” his allusions seriously characterize the captain’s obsession with the great power that has defeated him in the form of a godlike whale. But Wodehouse’s plethora of allusions generally have the comic effect of showing his characters as puny by comparison with the significant events alluded to. On the first page of The Code of the Woosters, Bertie, suffering from a hangover, alludes to the graphic story of Jael in the book of Judges, whose act saves the Israelites in their war with the Canaanites:

Indeed, just before Jeeves came in, I had been dreaming that some bounder was driving spikes through my head—not just ordinary spikes, as used by Jael the wife of Heber, but red-hot ones.

Wodehouse also quite often alludes to poets, from Shakespeare to Tennyson to some favorite Romantic poets. He particularly likes Keats, and often will quote from his sonnet “On First Looking Into Chapman’s Homer,” as he does in The Code of the Woosters speaking of Stiffy, impressed by Jeeves’ figuring out a stratagem to save the day: “She sat up, looking at him with a wild surmise” like his men looked at Cortez upon discovering the Pacific [sic]. A bit earlier, Stiffy emits a noise like the woman in Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan” who wails in the “savage place,” “holy and enchanted”:

It was with a sort of joyful yelp like that of a woman getting together with her demon lover, that the little geezer had spoken his name.

And then there’s the allusion to Sidney Carton, hero of Dickens’ Tale of Two Cities, who, in case you need reminding, goes to the guillotine in place of his beloved’s beloved so that she can have a happy marriage (‘Tis a far, far better thing I do…), though Bertie only dimly remembers the story:

I drew no consolation from the fact that Stiffy Byng thought me like Sidney Carton. I had never met the chap, but I gathered that he was somebody who had taken it on the chin to oblige a girl.

The humor in the equation of being guillotined with “taking it on the chin” needs no further comment.

“Hold on now, though,” you may be heard to exclaim before we finish here. “Just what exactly is this Code of the Woosters?” Well, I answer, throughout the novel, Bertie does keep making comments about what the Woosters are like, and at one point suggest that his “code” is tantamount to a medieval code of chivalry:

It is pretty generally admitted, both in the Drone’s Club and elsewhere, that Bertram Wooster in his dealings with the opposite sex invariably shows himself a man of the nicest chivalry—what you sometimes hear described as a parfait gentil knight.

So much for his dealings with Madeline and Stiffy. But the more telling line comes late in the novel when Stiffy is trying to get Bertie to take the rap in Harold’s place for stealing the policeman’s helmet, and she says “Didn’t you once tell me that the code of the Woosters was ‘never let a pal down’?” And this, of course, is what Bertie, in his Sydney Carton role, tries to do throughout the novel. At every point when one of his “pals” is “in the soup” as he would say, Bertie steps up: whether it is for Gussie Fink-Nottle, Harold Pinker, or his own Aunt Dahlia, Bertie is willing to go the extra m. for his friends and show them compash, however much the Bassetts and Strodes of the world may raise their accusatory chins at him.