https://www.petwantsclt.com/petwants-charlotte-ingredients/ Phillip Pullman once said “I’ve been surprised by how little criticism I’ve got [for His Dark Materials]. Harry Potter’s been taking all the flak….Meanwhile, I’ve been flying under the radar, saying things that are far more subversive than anything poor old Harry has said. My books are about killing God.”

https://www.merlinsilk.com/neologism/ Pullman has a point. While conservative Christian groups, particularly in the U.S., went into conniptions over Harry and Hermione learning to be witches and cast spells, assuming they must therefore be Satanic, they virtually ignored The Golden Compass, The Subtle Knife, and The Amber Spyglass, which cast organized Christianity in the role of villains, and “The Authority” as a weak and impotent being who ultimately dies. As a student at Oxford University, Pullman had studied English literature and focused on John Milton, particularly on Milton’s epic Paradise Lost, and in this trilogy gives us a very conscious retelling of Paradise Lost, but through a lens provided by William Blake: that Milton was “of the Devil’s party without knowing it.” In part, too, Pullman was rejecting the generation of fantasy-writing Christian Oxford dons who came right before him: Tolkien he rejected for writing essentially a “trivial” story in which the good were always good and the evil always evil. But C.S. Lewis is the true target of Pullman’s repudiation. “He struggles with big ideas,” Pullman says of Lewis’s Narnia books, but “I dislike the conclusions he comes to because he seems to recommend the worship of a god who is a fascist and a bully; who dislikes people of different colours; and who thinks of women as being less valuable in every way.” Pullman’s “Authority” is the god of Lewis and of His Dark Materials’ fundamentalist Church with its all-powerful Magisterium and its bullying General Oblation Board.

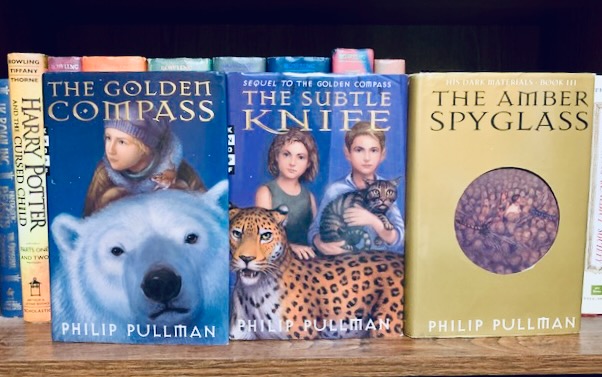

Pullman’s trilogy is a fantasy presented as a kind of coming of age story of two children, Lyra Belacqua (also known as Lyra Silvertongue because she’s so adept at lying convincingly), protagonist of the first book, The Golden Compass(1995, published as Northern Lights in the U.K.); and Will Parry, protagonist of the second book, The Subtle Knife (1997). The two move through a series of parallel universes, culminating in a visit to the kingdom of the dead and the realm of the Authority in the third book, The Amber Spyglass (2000). Individually, the novels have won a number of awards: Northern Lights won the 1995 Carnegie Medal (Britain’s award for outstanding new English language book for children or young adults), and in an online poll in 2007, it was voted the number one Carnegie Medal winner in the award’s 70-year history. The Observer listed Northern Lights as one of its 100 best world novels, and Time Magazine listed The Golden Compassas one of the “100 Best Young Adult Books of All Time.” The Amber Spyglass won the prestigious Whitbread Award in 2001—it was the first children’s book ever awarded the prize. That third book was more recently included in the Guardian’s list of the “100 Greatest Novels of the Twenty-First Century” as number six. In 2003, the full trilogy was ranked as number three in the BBC’s “Big Read” poll, and in 2019 His Dark Materials was included in the BBC’s list of the “100 Most Influential Novels.” And I am including it here as number 70 on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

Book One, The Golden Compass, is set in a world very like our own, where Lyra is first introduced as an eleven-year-old orphan being raised among the community of scholars at a recognizable Oxford University at a time that seems about the equivalent of Victorian England, except there are a few quirky differences—among them the fact that the Church is headed by the Pope in Geneva, where the seat of the papacy had been moved by Pope John Calvin. But the supreme characteristic of this world (indeed, the crowning innovation of Pullman’s whole creation) is his invention of the daemon.Every human in Lyra’s universe has a companion spirit called a daemon, which takes the form of an animal. The daemons of adult humans are static, they do not change, so that the daemon of Lord Asriel, Lyra’s supposed uncle (in fact her father) is a snow leopard, while that of Mrs. Coulter, the powerful head of the Church’s Oblation Board (and in fact Lyra’s mother) is a golden monkey. The daemons of children change with the moods of their humans, so that in the novel’s opening chapter Lyra’s daemon, Pantalaimon, is a moth, but changes to a mouse, an owl, and other forms in the course of the story. The daemon is not a separate being but is literally a part of the person’s psyche that takes a form external to the body. Most readers will interpret it as the person’s inner self made manifest. Many of us can relate to the closeness of human and daemon if we’ve had a pet dog or cat who has seemed to us a part of our heart. And Pullman certainly counts on that feeling as he presents us this world.

But for the idea of the daemon, Pullman has in fact taken a concept familiar to philosophy from the time of Socrates forward. The word daemon in ancient Greek referred to a lesser deity or guiding spirit. In The Symposium, Plato depicts the priestess Diotima describing a daemon as a kind of intermediary between humans and the gods. In the Apology of Socrates, Socrates claims to have a daemon that warns him, in the form of a voice, if he’s about to do something wrong. Modern readers have interpreted this as self-consciousness or the true nature of the soul. In Hellenistic times, daemons were divided into two types—benevolent or malevolent spirits. Early Christians used the term only to refer to malevolent spirits, but more often daemons seem to have been more like Guardian Angels. Among the Stoic philosophers daemonmight refer to reason itself. Pullman’s daemons may also owe something to Karl Jung’s concept of the anima or animus—an archetypal figure in folklore or psychology that represents the true inner self: like the daemon, the anima/animus was female for men, male for women. These notions must be kept in mind as we consider the importance of daemons throughout His Dark Materials.

A short summary of the entire trilogy is not possible, and besides, I wouldn’t want to include too many spoilers, so I’d like to provide a quick sketch of the first novel with just a few swipes at The Subtle Knife and The Amber Spyglass. Northern Lights (The Golden Compass) opens with Lyra sneaking into a meeting room at Jordan College in Oxford to watch her “uncle” Asriel report to the college on his experiences in the Arctic with the elementary particles called “Dust,” and the college funds his return to the north to research these particles. Soon after, children around Oxford begin disappearing, kidnapped by a mysterious group called “Gobblers,” who end up taking Lyra’s best friend Roger. Lyra wants to try to search for Roger, but a wealthy and powerful woman named Mrs. Coulter (secretly Lyra’s mother) turns up and takes her away from Oxford (but not before the Headmaster takes Lyra aside and secretly gives her a golden instrument called an alethiometer, which she believes he intends her to bring to Lord Asriel. In London, where Mrs. Coulter has taken her, Lyra discovers that the woman is head of the General Oblation Board, and so in charge of the Gobblers. She flees as soon as she can, and joins the Costas, a family of “Gyptians” (a clan who navigate the rivers and canals of Britain) who have also lost a child to the Gobblers. She travels with them and their clan northward in search of the missing children.

On this journey, Lyra learns the secret of her parentage. She also learns how to read the alethiometer, which is a kind of fortune teller. And she learns that Lord Asriel is being held prisoner in Svalbaard, guarded by armored polar bears. Lyra meets Iorek Byrnison, the exiled king of the armored bears, who agrees to come with her and the Gyptians, along with his friend Lee Scoresby, a Texan with a hot air balloon. On their way north, Lyra is kidnapped by Tartars, who take her to Bolvanger, headquarters of the Gobblers, where they are trying to perfect the process of “intercision”—cutting children apart from their daemons—a process that seems to leave them empty and soulless. Lyra is able to escape with the rest of the children, including Roger, but is closely pursued by Mrs. Coulter. Lee Scoresby rescues Lyra, Roger, and also Iorek Byrnison in his balloon, and they successfully escape with the help of a witch named Serafina Pekkala. They head for Svalbaard to rescue Lord Asriel.

In Svalbaard Lyra finds the king of the armored bears, Iofur Raknison, who deposed Iorek, to be in a kind of madness, wanting to be more like a human. She convinces him that if he fights Iorek Byrnison and kills him, she will become Iofur’s daemon. Iofur fights and dies, and Iorek regains his kingdom. Then he, Lyra and Roger go to free Lord Asriel. But he, too, seems in a kind of madness. He sees—as Lyra can see—a city apparently existing on the other side of the Northern Lights, a city that must exist, as Asriel reasons, in another universe, and he believes he can create enough power to build a bridge into that universe. He does so, and Lyra decides to follow him into that parallel universe. But I won’t tell you how he harnesses that power, nor will I give you any spoilers about the other two books if I can help it.

However, it is vital to review what Lord Asriel tells Lyra about Dust. The elementary particles cling to human beings, but not so much on children. It is not until the children mature and their daemons become fixed hat Dust settles upon them. The Church believes that Dust is evidence of Original Sin: Adam and Eve’s eating the fruit of the Tree of Knowledge is essentially their own adolescence, and Dust the knowledge that comes to the mature human being. To the Church, this is sin. But what if it isn’t? Lord Asriel believes that this is not sinful at all, but the point at which we become completely human, the point when we gain knowledge—which in its interpretation, the Church finds sinful. The Church’s purpose is to stifle knowledge and call it sinful.

In book two, we are introduced to Will Parry, a twelve-year old boy from our own world, whom Lyra meets in yet a third world, where Will has come seeking his lost father. We also meet Dr. Mary Malone, a researcher trying to understand dark matter, this world’s version of Dust. Will obtains the Subtle Knife, which can be used to cut passageways between parallel universes. But Lyra’s alethiometer is stolen by one of Mrs. Coulter’s allies who has found a way into Will’s world.

In the third volume, Lyra is imprisoned by Mrs. Coulter, who has learned of the prophecy that Lyra is destined to be the new Eve. The angels Balthamos and Baruch tell Will that he must bring the Subtle Knife to Lord Asriel as a weapon against the Authority, but instead Will goes to rescue Lyra. The two of them journey to the land of the dead (a common occurrence in epics like the Odyssey, the Aeneid, and Paradise Lost). Mary Malone discovers the true meaning of Dust, while Lord Asriel and Mrs. Coulter join forces to battle Megatron, the Authority’s Regent, and Will and Lyra try to rescue the Authority from the prison into which Megatron has placed him.

I’ve tried to give some idea of the complexity and the magnitude of the plot of the epic tale. And as I noted earlier, Pullman’s goal is to undermine he authority of fundamentalist Christianity, through a retelling of what he considers the founding myth of that sect, the Garden of Eden story of humanity’s loss of grace through the eating of the “forbidden fruit” of the Tree of Knowledge. Since Milton’s Paradise Lost is the supreme embodiment of that myth in literature, Pullman uses that narrative as his model, making the dashingly heroic Lord Asriel his defiant Satan figure. He includes the weak Authority character as God (and Megatron in the position of The Son, who in Milton’s epic battles and defeats Satan), as well as Lyra and Will as Eve and Adam, adolescents on the verge of passing out of their childhood innocence (which is also ignorance) into adulthood and true knowledge.

Pullman makes his debt to Milton clear in his trilogy’s title, His Dark Materials, an allusion to Book II of Paradise Lost, where Milton describes the shapeless forms in the realm of Chaos, destined to remain chaotic

Unless th’ Almighty Maker them ordain

His dark materials to create more Worlds,

A reference to the multiverse explored in the book’s action.

All of this makes the story a rollicking good read. Another notable virtue of Pullman’s writing is his ability to create believable, flesh and blood children as his protagonists. Pullman spent twelve years as a Middle School teacher, and his close personal knowledge of children of Lyra’s age allows him to avoid idealizing or sentimentalizing them, a quality YA readers immediately recognize.

Book publishers like to label books by pigeonholing them into narrow boxes like “YA.” But Pullman didn’t have in mind targeting a particular age group when he wrote His Dark Materials. The retelling of Paradise Lost itself is evidence that a more adult readership is implied. But the theological, philosophical, and scientific ideas in the work invite a very sophisticated reader.

Everyone will not love this trilogy. In particular conservative Christians—or Jews or Muslims, for that matter—will find it unpalatable. But one should perceive that Pullman, who identifies as atheist, is not attacking God or belief in a supreme being per se: the grandfather who raised him was himself an Anglican priest, and he has no complaints about his grandfather’s theology. His target is the churches that “bully” their parishioners, and that deny science and human rights. In this a number of more progressive Christians have come to his support, most notably the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, who acknowledged that the trilogy was not an attack on Christianity, but rather on repressive churches: “What would the church look like,” Williams asked, “what would it inevitably be, if it believed only in a God who…needed unceasing protection? It would be a desperate, repressive tyranny.”