Robert Graves was a highly acclaimed English author generally associated with the earlier twentieth century (though in fact he lived to be 90 and died in 1985). He was a poet, a memoirist, a critic, a biographer, a classical scholar and translator, and a novelist, publishing nearly 150 significant texts in his lifetime. Among these were his well-known memoir Goodbye to All That (1929), which relates his experiences in the First World War (a book included in The Guardian’s 2014 list of the 100 greatest non-fiction books in English, and Modern Library’s 1999 list of the greatest non-fiction books of the 20th century), and The White Goddess (1948), which approaches the study of mythology from the creative point of view of a poet—an idiosyncratic study that anthropologists have rejected but that has been influential with poets, most notably Ted Hughes and Sylvia Plath. Neither of these books has ever been out of print.

Graves wrote a 1927 biography of his friend T.E. Lawrence. He published 28 volumes of poems between 1918 and 1963, receiving the “Queen’s Gold Medal for Poetry” in 1968. Recently released records reveal that he was strongly considered for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1962, ultimately losing to John Steinbeck. His translation of Suetonius’s The Twelve Caesars for Penguin remains the best-known English translation of the text. And it was his study of Suetonius that seems to have prompted his groundbreaking historical novel, I, Claudius, and its sequel, Claudius the God.

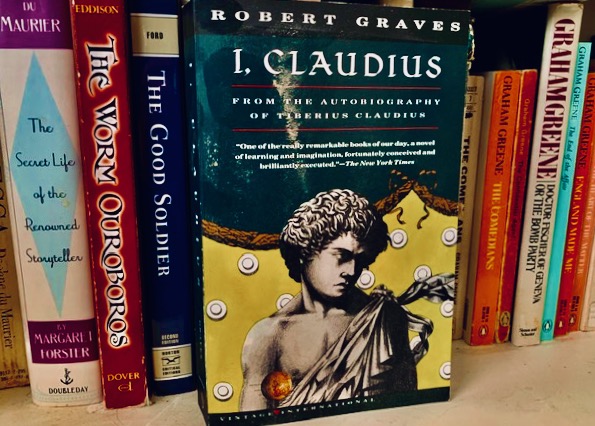

Graves received the prestigious James Tait Black Memorial Prize for 1934 for I, Claudius. It was ranked as number 40 on Modern Library’s 1998 list of the 100 greatest English language novels written in the 20th century, and in 2005 was included in Time magazine’s list of the 100 best English language novels since 1923. It was also included in Penguin Classics list of the top 100 novels as chosen by their readers. And it appears as number 40, alphabetically, on my own list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

Graves’ novel purports to be a secret memoir written by the future Roman emperor Claudius, who is a child of the imperial family, but a highly unlikely protagonist. Though he is the son of the general Drusus, the nephew of the emperor Tiberius, and the great nephew of Augustus Caesar, Claudius is a weak and stammering youth who tends to be an embarrassment to the family, who consider him mentaly deficient and unfit for public office, and keep him well in the background during imperial functions. Left to his own devices, Claudius becomes a historian and a scholar, and since he is not a threat or rival to other members of the family, he is able to describe the intrigues among his more prominent contemporaries. Graves has Claudius hide his memoir, hoping it will be read centuries later, when it will no longer be dangerous to speak these truths about the Julio-Claudian dynasty. Graves implies that the novel is this same long-hidden manuscript.

Using his intimate familiarity with Suetonius and with Tacitus, Graves focuses first on the machinations that put Tiberius on the imperial throne to succeed his step-father Augustus. This involves the disgrace and exile of Augustus’s chosen successor, his grandson Agrippa Postumus, which Claudius suggests was arranged by Livia—wife of Augustus and mother of Tiberius (which also makes her the grandmother of Claudius himself). Livia is addicted to power, having been empress of Rome during Augustus’s reign, and knows she will have significant influence over her son Tiberius if he becomes emperor. There is also the suggestion that Livia, or Tiberius at Livia’s urging, was instrumental in poisoning Claudius’s older brother Germanicus (also her grandson), whom popular acclaim might have made emperor. With Germanicus and Postumus out of the way, Livia clears the way for Tiberius’s rise to power. Unfortunately, it leaves Germanicus’s son (and thus Claudius’s nephew), the criminally insane Caligula, as a candidate for the imperial throne when he comes of age (It later comes to light that Caligula himself had a hand in his father’s murder). As for Claudius—well, nobody bothers plotting to kill him. The stammering bookish nerd can’t possibly be considered emperor material by any of the feuding rivals for the throne.

Of course, we know from the beginning of the novel that Claudius in fact will at some point ascend to the imperial throne. How he ends up doing it is the ultimate point of the book, making the novel a classic “triumphant underdog” story that’s well worth reading. It spans the 85-year period of Roman history between two epoch-changing assassinations: from that of Julius Caesar in 44 BCE (resulting in the rise to power of Augustus) to that of Caligula in 41 CE (resulting in the ascension of Claudius himself). Graves is faithful to the facts of history with which he was so familiar, but gives the characters themselves his own fictional twist.

Tiberius’s reign is no a happy one. He becomes more and more hated by the citizens of Rome, and begins to rely on Sejanus, the captain of his praetorian guard, for protection. Livia, knowing her end is near, invites Caligula and Claudius to a dinner at which she predicts that Caligula will be the next emperor, and that Claudius will follow him. And she asks that Claudius declare her a goddess after she has died, though she also admits to have poisoned a number of people. When Claudius is called to her deathbed, she tells him she realizes he is no fool.

Without his mother’s comparatively restraining influence, Tiberius loses all inhibitions and executes hundreds of influential citizens on false charges of treason. Then he retreats to Capri leaving Sejanus in command of Rome in his absence. Sejanus, unsurprisingly, plots to overthrow the emperor and seize all power himself, but Tiberius, warned of this plot, joins forces with Caligula, and having defeated Sejanus, has him executed with all his children. Upon the ailing Tiberius’s death, Caligula becomes emperor, and recalls Claudius from Capua, where he has been writing his history, so that Claudius witnesses the enormities of Caligula’s reign of madness, But I won’t provide any spoilers here.

I, Claudius was so popular upon its release in 1934 that it was followed almost immediately by a sequel, Claudius the God, which details the thirteen years of Claudius’s imperial reign and his ultimate overthrow and murder by his own stepson, Nero. The books were critically acclaimed, winning England’s most prestigious literary award at the time. They were pioneering works in the area of historical fiction, and remain eminently readable and enjoyable, especially because of the vivid characterization of humble underdog Claudius, Machiavellian Livia, ambitious Tiberius, noble Germanicus, bullying Sejanus, deranged Caligula, and a host of others.

Many of you may be too young to have watched the thirteen-episode 1976 BBC television series I, Claudius, which covered the story as told both in the novel of that name and the sequel. In the title role of the stammering, twitching Claudius, Derek Jacobi had his breakthrough role and became an international star. Jacobi won a BAFTA Award for is performance, as did Siân Phillips as the deliciously malevolent Livia. The series also starred a very young John Hurt as a very mad Caligula, and future Starfleet Captain Patrick Stewart as the bullying Sejanus. You can still view this entire fine series, which I did recently, on Prime Video or Apple TV, and I would definitely recommend you do so, but not as a substitute for the books, which are a treasure in themselves.