In 1976, Saul Bellow became the seventh American to win the Nobel Prize in Literature (if you don’t count T.S. Eliot, who had eschewed his American citizenship well before his award). Bellow had just won the Pulitzer Prize for his novel Humboldt’s Gift. He had already become the only writer in the history of the award to win the National Book Award for fiction three times—with his 1953 novel The Adventures of Augie March, 1964’s Herzog, and 1970’s Mr. Sammler’s Planet—but the Pulitzer seems to have raised him to the top of the Nobel committee’s list. When it rains, it pours.

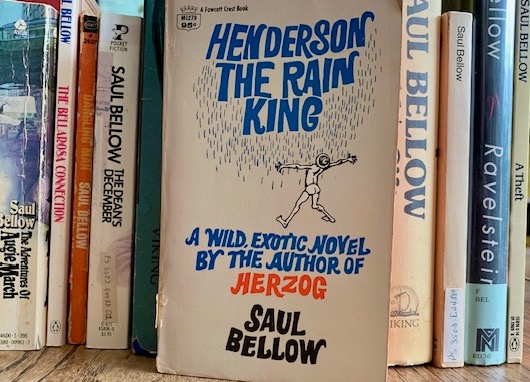

In graduate school in 1976, I figured I was obliged to read Humboldt’s Gift, which I dutifully did, and it struck a sympathetic enough chord in me to lead me to Bellow’s other novels, including Augie March, Herzog, and Mr. Sammler. But the book that really resonated with me more than any of the others was his follow-up to Augie March, 1959’s Henderson the Rain King.

In that preference I am not alone. Henderson the Rain King was reputedly Bellow’s own favorite of all his novels, and he is quoted as saying that of all his characters, Eugene Henderson, protagonist of the book, was the most like himself. The book was well received upon publication, and in fact was selected by the Pulitzer Prize committee for the 1960 prize in fiction, but in an unusual development, the Pulitzer board chose to override that recommendation and gave the prize to Allen Drury’s Advise and Consent, a conservative Cold War novel about communist influence in government—obviously a politically motivated choice that reflects no honor on the Pulitzer board. But I digress. Henderson the Rain King was subsequently ranked as number 21 on Modern Library’s famous list of “The 100 Best Novels in the English Language.” And it ranks as book #11 (alphabetically) on my own list of “The 100 Most Lovable Books in the English Language.”

Henderson is a character with whom many readers can probably identify. He’s a rich and successful middle-aged man in peak physical condition, but he suffers from what most people would probably call a “mid-life crisis,” which in his case manifests as a spiritual and emotional emptiness, an inner voice that keeps crying “I want, I want,” but the object of that inner craving eludes him. Henderson decides to go on what is essentially, in the tradition of the medieval romance, a quest for identity and self-knowledge. In his case, he goes to Africa.

Perhaps this is one reason I love this book: Unlike Bellow’s other books, the action occurs outside Bellow’s more typical Chicago settings, or indeed of any North American cities, but rather in the more exotic villages of Africa. In searching for his own meaning, Henderson returns to the cradle of human existence. It has been pointed out that a number of details of the novel are drawn from the book The Cattle Complex in East Africa, a study by Melville Herskovits, Bellow’s anthropology professor and his senior thesis advisor at Northwestern University in 1937. In the novel, Henderson hires a native guide who takes him first to the village of Arnewi, where he tries to help the village with a water crisis but fails disastrously. Moving on to the village of Wariri, he shows his great strength by moving a heavy statue of the local goddess Mummah which, to his astonishment, gets him proclaimed Sungo, the Wariri Rain King. It seems hardly necessary to point out that these images of rain, water, the symbol of regeneration, of new life, reflect Henderson’s own rebirth.

In this capacity as Rain King, Henderson forms a close friendship with King Dahfu, the Wariri king who has been educated in the west. The core of the book lies in the long and lively philosophical discussions between Henderson and Dahfu. These discussions form the true core of the novel, and in this the book is purely Bellow, with Henderson and Dahfu performing the roles of typical characters in his works—the naïve or foolish seeker of knowledge, and the wise mentor, a character Bellow refers to as the “Reality Instructor.” It is in these discussions that Henderson works out his spiritual longing, the disjunction between body and spirit, between self and the world.

I don’t want to include any spoilers, so I won‘t tell you about the lion that Dahfu must hunt, or how Henderson leaves Africa and his Rain-King status, because I think you’d much prefer to read the book yourselves. Suffice it to say that Henderson the Rain King perfectly exemplifies what the Nobel committee praised in Bellow’s work when presenting him the prize: “A mixture of rich picaresque novel and subtle analysis of our culture, of entertaining adventure, drastic and tragic episodes in quick succession interspersed with philosophic conversation.”

If you don’t trust my judgment, or that of the Nobel committee, maybe you can trust Joni Mitchell, who was inspired by her reading of Henderson the Rain King on a plane. Early in the novel, Henderson, on his flight to Africa, looks out his window and observes the clouds below him:

“And I dreamed down at the clouds, and thought that when I was a kid I had dreamed up at them, and having dreamed at the clouds from both sides as no other generation of men has done, one should be able to accept his death very easily.”

Mitchell says she immediately closed the book and began writing her most famous song. If the book could have that kind of effect on Joni Mitchell, think what it can do for you! Do yourself a favor, and read this novel if you haven’t already. It’s a good one.