As ranked on our podcast, “Between the Covers,” through Tuesday, May 27, 2025. To tune in to the podcast, try this link: https://betweenthecoverspodcast.podbean.com:

1. http://economiacircularverde.com/que-es-la-economia-circular/ Catch-22 by Joseph Heller

Catch-22 is a satirical, anti-war novel that follows the increasingly frantic attempts by the American bombardier Captain John Yossarian to stay alive. He has become convinced that everyone, not only the Germans but also his own incompetent and self-interested superior officers, is out to kill him, and so his only goal in life becomes the avoidance of death: He aims to “live forever or die trying.”

Order Cheap Tramadol 2. Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen

Pride and Prejudice is a delightful comedy of manners, written with brilliant wit and what Austen would call a characteristic “archness.” It contains some of the most memorable characters in British fiction, and its theme of the superficial perceived virtue that first impressions might create, as opposed to the deeply committed virtue of a truly good person, is one that still resonates, and might be considered a genuine “truth universally acknowledged.”

Tramadol For Sale Online Cod 3. Never Let Me Go by Kazuo Ishiguro

Ishiguro takes on genetic engineering and supporting technology, in order to raise questions about what it means to be human …. Are cloned beings as “human” as people born “normally”? Do they even have a soul? The dominant society in Ishiguro’s novel would say no, but reading Kathy’s account will convince you otherwise. Does life have a purpose—and is it the same for cloned individuals as others: to love?

Tramadol Prescription Online 4. Atonement by Ian McEwan

There is a part four, that takes place six decades later. Here an octogenarian Briony, now a well-known novelist, discusses her latest book—which, it is implied, we have just read. And here we discover that the novel is also about fiction itself. How much of what we have just read is true, and how much of it is the invention of the (fictional) author? And how much of that invention is in fact a gesture of atonement? You’ll need to read the book to find out. And to find out how much you yourself are willing to forgive Briony. Or McEwan.

5. To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee

Racism is not the only theme in To Kill a Mockingbird, but it’s the most pervasive. The book is also a condemnation of both the schools and the courts—two institutions that should define and promote justice, but often fail to do so. It’s a feminist text as well, in which tomboy Scout fights against the views of femininity promoted by Aunt Alexandra and her ilk. And of course it’s a story of heroism that suggests even one person can make a difference in a difficult situation.

https://www.circologhislandi.net/en/conferenze/ 6. Slaughterhouse-Five by Kurt Vonnegut

Billy [Pilgrim] does spend the rest of his life…trying to get people to stop fearing death and convert to the Tralfamadorian view of things:

The most important thing I learned on Tralfamadore (Billy tells people) was that when a person dies he only appears to die. He is still very much alive in the past, so it is very silly for people to cry at his funeral. All moments, past, present and future, always have existed, always will exist.

Certainly this is comforting to Billy, who believes he is spreading a reassuring message. Whether Vonnegut wants us to think this way is anyone’s guess, but it is at least a message of acceptance. Vonnegut’s real purpose is to retell the horror of his own experience as a POW during the Dresden firebombing, the terrible aftermath of searching the rubble for the endless corpses, a horror he had carried with him for 24 years before he finally told the story.

7. The Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger

These are rarified heights for a modest little book like Salinger’s. Parts of the novel were published in magazines right after the Second World War, but The Catcher in the Rye was not published in book form until 1951. Salinger intended the novel for an adult audience, but since teenagers could relate easily with Salinger’s sixteen-year-old protagonist Holden Caulfield and his alienation from a society he finds superficial and “phony,” his depression and angst over the loss of innocence, his search for identity, and his feelings of rebellion, it was inevitable that the novel would become a staple in high school classes across the country.

8. Middlemarch by George Eliot

On a related note, Middlemarch also deals with what at the time, and for decades beyond, was called “the woman question.” Dorothea is intelligent, ambitious, and dedicated to improving the lives of her neighbors. Before her marriage she has the notion of redesigning all the living spaces of the tenants on her uncle’s manor. And she marries Casaubon fully expecting to help him in researching his great project, the study The Key to All Mythologies. But she is thwarted at every turn. Toward the end of the book Eliot comments that Dorothea, though she had the makings of a heroic woman like Antigone or St. Teresa, lived “amidst the conditions of an imperfect social state, in which great feelings will often take the aspect of error, and great faith the aspect of illusion.”

9. The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

The novel is certainly about social status and the nature of New York’s “high society” in the late nineteenth century. Opinions of the novel have varied over the years since its publication and many have seen May as ultimately a strong woman protecting her marriage and family against the scheming homewrecker Ellen. More recently, readers have found Ellen more sympathetic and seen May as manipulative. It seems to me that Wharton looks on society as benign on the surface but hypocritically ruthless and malicious. The single strongest impression one takes from the novel is the feeling of intense but confined and inexpressible passion, a love forever anticipated but never realized, a love whose only outlet may be the touch of a hand or a lock of hair brushing the cheek..

10. The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier and Clay by Michael Chabon

“Having lost his mother, father, brother, and grandfather, the friends and foes of his youth, his beloved teacher Bernard Kornblum, his city, his history—his home—the usual charge leveled against comic books, that they offered merely an escape from reality, seemed to Joe actually to be a powerful argument on their behalf…”

11. Emma by Jane Austen

The novel, set in the small fictional village of Highbury, follows the relationships among the more important families of that tiny village, itself a microcosm of early nineteenth century society of Regency England, a society in which estates were entailed upon male relatives, and women could not inherit. A society in which, as a result, women were absolutely concerned primarily with marriage as, essentially, their only possible road to success and respectability was to make a good marriage. By which is meant finding a wealthy husband. These are the particular concerns of Pride and Prejudice, as we’ve seen. Emma herself is, however, immune from this necessity: She has a personal fortune from her father that will allow her to live comfortably on her own, and thus, relieved of the pressure that most of her class and gender would feel, she is able to maneuver in this society with the agency of a man

12. David Copperfield by Charles Dickens

But chiefly one reads Dickens for the characters. It’s no coincidence that “Dickensian” has become an adjective often applied to memorable characters, especially those who are larger than life, full of warmth or jollity, or weirdly grotesque. Uriah Heep, the “‘umblest” creature on earth, is certainly one of these, as is Copperfield’s Aunt Betsey, who stormed out of the house when David was born because he was not a girl, and her kite-flying houseguest Mr. Dick, who is obsessed with the execution of King Charles I two hundred years earlier. But the most Dickensian of all David Copperfield characters is the impractical but ever big-hearted spendthrift, the jovial and optimistic Mr. Micawber. The novelist J.B. Priestley wrote that “With the one exception of Falstaff,” Micawber was “the greatest comic figure in English literature.” Of the fourteen different film or television versions of the novel, George Cukor had the genius to cast W.C. Fields as Micawber in 1935, and I’ve never been able to see him as anybody else.

13. A Prayer for Owen Meany by John Irving

The end of the book brings all of these things together in surprising ways, which I won’t discuss to avoid spoilers. But they work out in a way that causes John Wheelwright to praise Owen Meany as a prophet and hero and, as the novel’s first sentence says, the reason John is a Christian. Don’t get me wrong, A Prayer for Owen Meany is not an evangelical book—though it may be the kind of story that a disciple of Jesus of Nazareth might have told long after the crucifixion, after he’d had time to put it all together to make sense of things in his own mind. Owen’s story does push readers to consider the universal ideas of fate, chance, and providence, and the question of which, if any, of these things determine one’s life. And, of course, the novel forces the reader to consider where faith actually comes from, and whether it is a logical response to events.

14. The End of the Affair by Graham Greene

This is a novel that was seemingly close to Greene’s heart. It’s a psychological drama whose structure is reminiscent of an old morality play, with Sarah in the role of Everyman, Bendrix cast as the devil, and God himself in the role of the Good Angel. When Sarah dies about halfway through the book (did I say that out loud?) Maurice is left with no one to hate but the God who has robbed him.

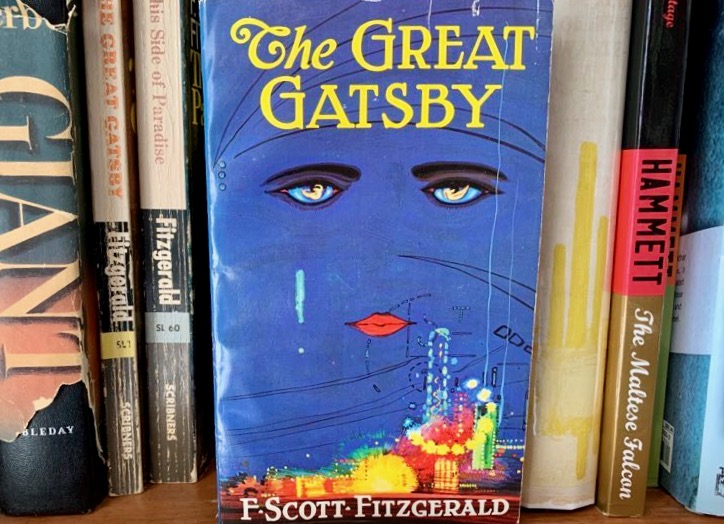

15. The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Perhaps what makes Gatsby such a profoundly affecting story is its aspects of tragedy. An admirable self-made figure who rose from humble obscurity to a position of great wealth, Gatsby easily fits Aristotle’s characterization of the tragic hero as a person superior to others in some way, who falls from his high position as a result of his hamartia, literally his failure to hit the mark, usually interpreted as a “tragic flaw” or, more accurately, an “error of judgment.” Gatsby’s error is his monomaniacal quest to win back Daisy through his pursuit of the elusive “American dream.”

16. Demon Copperhead by Barbara Kingsolver

Of course, knowing Dickens gives you an idea of the role these characters are going to play in the story. But the plot of Demon Copperhead is not therefore predictable, as Kingsolver translates these characters’ motivations and effects on the protagonist into a completely different milieu of time and place. Ultimately, what’s important about the influence of Dickens on Kingsolver’s book is not the superficial correspondences of plot or character, but rather their very significant agreement in terms of theme and authorial intent. In an afterword to her novel, Kingsolver writes, “I’m grateful to Charles Dickens for writing David Copperfield, his impassioned critique of institutional poverty and its damaging effects on children in his society. Those problems are still with us. In adapting his novel to my own place and time, working for years with his outrage, inventiveness, and empathy at my elbow, I’ve come to think of him as my genius friend.” It is precisely those social evils that Kingsolver has directly in her sights in this novel: Most broadly she attacks the institutional poverty of former coal-mining areas of her native Appalachia—a fact she lays unequivocally at the door of the owners and exploiters of those coal fields and the powerful political forces that supported them.

17. Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

One of the novel’s themes is the inescapable nature of time—underscored by the constant remembrance of things past in the characters’ minds as well as this inevitability of death and the meaning of life in the face of it: the novel gives us no definitive answer to this overwhelming question, but we are told that Clarissa, known in London society as the perfect hostess, “is always giving parties to cover the silence.”

18. Song of Solomon by Toni Morrison

Essentially a Bildungsroman or “coming of age” novel, Song of Solomon follows the life of its hero, Macon “Milkman” Dead III, from birth to maturity as he comes to recognize and understand his true heritage. The novel opens as the Black insurance agent Robert Smith leaps from the roof of Mercy Hospital, falling to his death while trying to fly on a pair of blue silk wings (the image of flight becomes important in the book), as dozens of people watch. One of these is the pregnant Ruth Dead, who goes into labor and in the ensuing turmoil is taken into the hospital where she gives birth the first African American baby ever born there—Macon Dead III.

19. The Nickel Boys by Colson Whitehead

As Elwood becomes more and more like Turner, he chides himself, lying awake at night and thinking that “In keeping his head down, … he fooled himself that he had prevailed. … In fact he had been ruined. He was like one of those Negroes Dr. King spoke of in his letter from jail, so complacent and sleepy after years of oppression that they had adjusted to it and learned to sleep in it as their only bed.” And accordingly he comes up with a plan to try to obtain justice one more time. Revealing what that is would be spoiler territory I won’t enter.

20. Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel

In telling the story of Henry’s divorce from Catherine, his marriage to Anne, and most importantly his break with Rome, Mantel focuses in great detail on her chosen protagonist, the much reviled Thomas Cromwell. What if, she seems to ask, Cromwell has been unfairly maligned by history—by his contemporaries who were jealous of his political skill and legal acumen, by members of the court who perhaps looked down upon him for his humble birth, by Catholics who saw him as ruthless because of his support for the Protestant cause in England.

. 21. Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

The multiplicity of possible interpretations of the text—the indeterminacy of the novel’s meaning—is one characteristic of the post-modern. It’s also an example of the postmodern staple metafiction—a form of fiction emphasizing its own fictionality so that the readers are never unaware that they are perusing a fictional text. The novel also encourages an interactive reading process, a post-modern technique known as hypertext that, like an electronic text, may be read straight through, or by jumping between Shade’s lines and Kinbote’s commentary on them.

All of these innovative techniques make Pale Fire a revolutionary and incredibly influential novel, and one that deserves to be on my exclusive list. Besides, it’s just so darn funny it’s hard to resist.

22. The Once and Future King by T.H. White

And that of course is the legend White is playing on with the title of his work. Like Malory’s it’s a compilation of related books written separately—for Malory, it was eight different books; for White it was four. For Caxton, the legend of Arthur’s return can be applied to the advent of the Tudor monarchy; for White, it may be that at the end of his novel, when he gives us a long discussion of the various warring thoughts Arthur struggles with as he worries his career has been a failure, the final return of Arthur, drawing from the imagery with the Second Coming of Christ, may be in White’s own time: recall he writes this last book in 1940, during Britain’s darkest hour. What better time for the return of Arthur—when the king may complete his task and create a truly just society after defeating the dark forces of Nazis who believe raw power is the only criterion for government. It may be that this is what makes White’s novel as relevant today as it was in 1940.

23. Watership Down by Richard Adams

When I read the book (well past my own YA days) I was absolutely carried away by the adventure story of Hazel and Bigwig and their journey to a new home at Watership Down. Their Odyssey recalls the great myths of the western world—like, for instance, well, the Odyssey. Or Moses leading the chosen people to the Promised Land. And this is particularly unusual because the novel’s protagonists are, well, rabbits.

24. Heart of Darkness by Joseph Conrad

Marlow’s job is to transport ivory. He has heard all the platitudes about the Europeans’ duty to bring civilization to the savages of Africa, but is shocked by the condition of the indigenous people who have come under the influence of the “civilizing” European traders—people who are sick or worked nearly to death, or, in the case of some who work for his company on the boat, “detribalized” natives who have been wrenched from their tribal culture and found no code of ethics to replace it. These latter have, as Marlow puts it, no “restraint.” He comes to realize fairly quickly that the high moral excuse for colonization i nothing but a bald-faced lie:

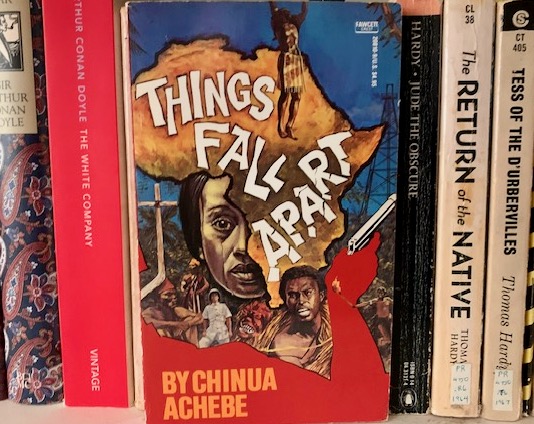

25. Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe

chebe’s novel utilizes traditional Western literary patterns as well as the English language, and is in many ways a response to Conrad’s Heart of Darkness while borrowing its title from a poem by William Butler Yeats. But Achebe subverts western colonization by showing the pre-colonial culture of the Igbo as a complex, well-structured society, perfectly competent at governing itself, and not as a tribe of savages in need or civilizing by western powers. And it was the first of its kind to show the ugly face of colonialism to the colonial powers in their own language. And that’s why it belongs on this list.

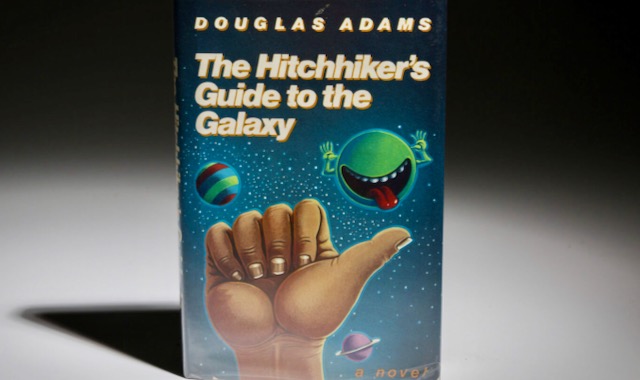

26. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams

But there is more to Adams than a witty punster. The books are a parody of serious science fiction (Adams started his career as a script editor for “Dr. Who”). But more than that they unflinchingly lampoon contemporary western society and pessimistically but humorously poke holes in the search for the ultimate meaning of life, the universe, and everything (which, as you will know if you’ve read the first book, is actually 42). This was the answer as delivered by a great computer in the first novel–an answer that the computer took seven million years to arrive at. Since people don’t quite get it they now seek to find the correct question. As Adams summarizes in The Restaurant at the End of the Universe, “The story so far: In the beginning the Universe was created. This has made a lot of people very angry and been widely regarded as a bad move.” And perhaps most seriously, it’s the human race that Adams finds the most absurd of all:

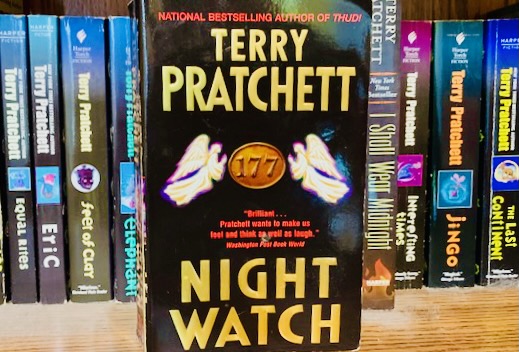

27. Night Watch by Terry Pratchett

More than many of the earlier novels in the Discworld series, Night Watch is a “black humor” novel, or, as Pratchett himself said, it contains “the humour that comes out of bad situations.” There is nothing funny about the kind of torture that the “Unmentionables” of the novel engage in, nor about the sort of despots who utilize such methods. The power mongering and paranoia displayed by the “Homicidal” and the “Mad” are humorous in the exaggerated way they act, but it’s a grim humor when we reflect how close it really is to reality. But responding to the comments of critics who called Night Watch a “dark” book, Pratchett said “I am kind of puzzled by the suggestion that it is dark. Things end up, shall we say, at least no worse than they were when they started… and that seems far from dark to me. The fact that it deals with some rather grim things is, I think, a different matter.”

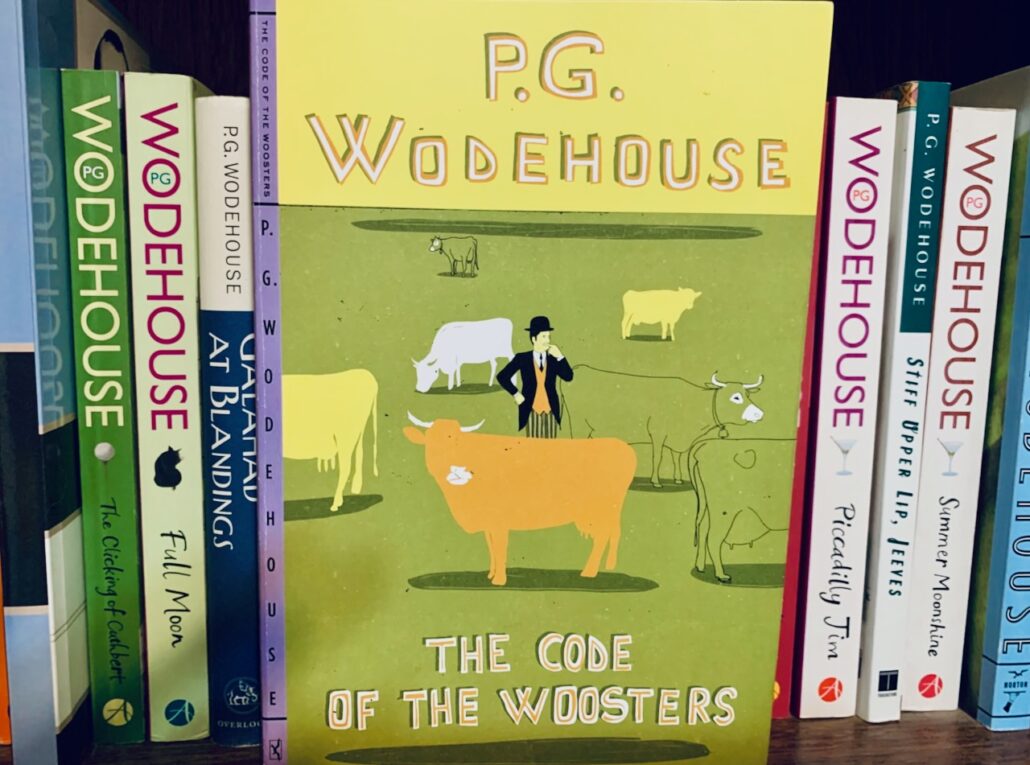

28. The Code of the Woosters by P.G. Wodehouse

In The Code of the Woosters, the protagonist Bertie Wooster is, as usual, a helping figure in the courtship of two of his old school pals Gussie Fink-Nottle (engaged, off and on, to the dramatic and sentimental Madeline Bassett), and the hapless curate Harold “Stinker” Pinker (hoping to marry the brash Stephanie “Stiffy” Byng). Both sets of lovers are on-again-off-again, mainly because of the chief blocking figure, Sir Watkyn Bassett, owner of a great country house called Totleigh Towers, who happens to be Madeline’s father and Stiffy’s uncle, and who is not ready to consent to either marriage. He is assisted by his very large and muscular friend Roderick Spode and by the local Constable Oates, who has a particular vendetta against Stiffy because her dog likes to attack policemen. Bertie, on the other hand, is aided by his Aunt Dahlia and by the one person who is never at a loss no matter what the difficulty, his gentleman’s gentleman Jeeves.

29. 1984 by George Orwell

The story focuses on the protagonist, Winston Smith, a government employee in the ironically named Ministry of Truth. His job is to change and rewrite all past news stories to match what the government currently has decided the “truth” actually is…. And Winston must make all necessary changes to all public records as well as news stories posted in the past, so there is never any documentary evidence that the current lie is not the truth. Books, of course, must be destroyed if they do not reflect the current Party line. As the Party slogan insists: “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past.”

30. Brave New World by Aldous Huxley

The future is a nightmare comprising a predetermined and unalterable caste system, psychological conditioning beginning at birth, the elimination of mothers, fathers, family, and romantic love—things that elicit emotions that can’t be easily controlled—and quashes individuality, all in the name of an all-powerful world state.

31. A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway called the novel his “Romeo and Juliet” story, and the five books do suggest the five-act structure of an Elizabethan tragedy, with the crucial turning point in Act Three (with Lieutenant Henry’ rejection of the war and dive from the bridge to freedom) and the tragic denouement in Act Five. Some critics have found the novel closer to pathos than tragedy, but it could be argued that Lieutenant Henry’s “anagnorisis” or tragic knowledge in the end may not be an insight into the meaning of suffering as much as it is insight into the meaninglessness of suffering in the Wasteland following the meaningless war.

32. All the King’s Men by Robert Penn Warren

You would think that a novel about political corruption by a populist politician who gets elected on the strength of wild promises but uses his office mainly for personal profit would be obsolete by now, nearly 80 years after its publication, because of course voters will have learned by now to recognize lies when they are blatantly false, but surprisingly Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men remains as relevant now as it was just 50 years ago when the story of corruption in the Oval Office was explored by Woodward and Bernstein in their allusively titled book (and movie) All the President’s Men.

33. The Things They Carried by Tim O’Brien

These themes—truth, courage, and morality—are, being abstractions, all things that O’Brien says true war stories are never about. However, there is always some part of a true war story that is not absolutely true, and that dictum may be one of the untrue things about this story collection. At least one of the chief things a reader takes away from these stories is the sense that such things as truth, courage and morality are not clear cut, perhaps are even turned on their heads, in the reality of the U.S. war in Vietnam.

34. The Color Purple by Alice Walker

This is an old fashioned epistolary novel, a form going back to the very origins of the novel as a literary form in the 18th century. It consists of letters written by two sisters, over the course of some 40 years. Walker said in a 1983 interview that she adopted the form as a practical way of solving the problem that one of her protagonists is in Georgia while the other is in Africa. Neither of the sisters actually receives the other’s letters, but the two of them manage to feel closer to each other through the writing of them. Essentially the book is feminist in intent, or as Walker called it, “womanist” (what she calls feminist as applied to women of color, whose experiences are different from those of other feminists). Celie and Nettie are poor Black girls in rural Georgia, who in spite of extreme poverty and early trauma achieve empowerment by the novel’s end.

35. Midnight’s Children by Salman Rushdie

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, Rushdie asserts that his chief theme was that “All of India belonged to all of us.” Unlike the Islamic state of Pakistan, partitioned off from India on the day before Indian independence, India was from the beginning intended to be a secular state, in which the many different cultural traditions, religions, and languages form a single multicultural unity. Thus Saleem of the giant nose could be reflective of elephant-nosed Ganesh, the Hindu god of literature (even though Saleem—and Rushdie himself—were born Muslims). The telepathic forum of all midnight’s children reflected Saleem’s vision of that dream. The authoritarian crackdown of Mrs. Gandhi’s Emergency, as presented in the novel, was a betrayal of that vision of democratic multiculturalism. And Rushdie believes the book is just as relevant today, with India’s recent veering once more to the authoritarian right.

36. Moby-Dick by Herman Melville

At times his language too rises to the heights of Shakespearean power. … Of these, the most memorable are some of Ahab’s speeches, like Hamlet’s soliloquies or Satan’s mighty lines from the first books of Paradise Lost, full of power, allusion, rhythm and charisma. You cannot read Ahab’s explanation of his need for vengeance without seeing it as the human struggle against a hostile universe in microcosm:

37. Babbitt by Sinclair Lewis

Babbitt’s own stature reaches its height in Zenith on the day he is elected vice-president of the Boosters’ club. On that same day, his friend Paul shoots his wife. The incident is a major turning point in Babbitt’s life, and the crisis reaches a peak when his own wife and daughter leave him alone and go off to visit relatives. Babbitt’s misgivings about his life come to the fore—he begins to lead a more bohemian lifestyle, has an affair with another woman, drinks and parties, and even begins to think sympathetically of the socialist Doane.

38.The Little Stranger by Sara Waters

It’s at this point that careful readers will begin to suspect, if they haven’t done so already, that Faraday is an unreliable narrator. After all, Roderick, Caroline, Betty and Mrs. Ayres all become convinced of some malevolent presence in the house. Caroline suspects that somehow Roderick is projecting his presence in the house, disturbed at his forcible removal. Betty believes that the malevolent spirit of some former servant is haunting the second floor of the mansion. Mrs. Ayres comes to believe that the spirit of her beloved daughter Susan is trying to reach her from beyond the grave—and Faraday suggests that she, too, should be committed to an asylum. It’s not until it is too late that Faraday finally entertains the possibility that the house is “consumed by some dark germ, some ravenous shadow-creature, some ‘little stranger’ spawned from the troubled unconscious of someone connected with the house itself.”

39. Complete Tales by Edgar Allan Poe

Poe’s own starting point is the assertion that in every piece of writing, the “point of greatest importance” is the text’s “unity of effect or impression.” Since as he asserts “All high excitements are necessarily transient,” for the text to have its strongest effect, the reader should be able to peruse it at a single sitting, not exceeding one or two hours. Thus a novel will of necessity have a weaker effect than a short story. Only thus can the reader receive “the immense force derivable from totality.”

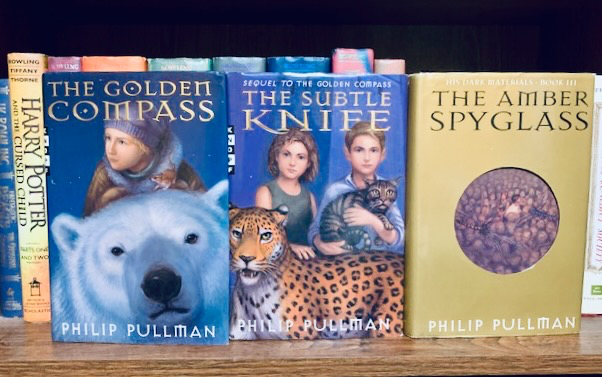

41. His Dark Materials by Phillip Pullman

Pullman’s trilogy is a fantasy presented as a kind of coming of age story of two children, Lyra Belacqua (also known as Lyra Silvertongue because she’s so adept at lying convincingly), protagonist of the first book, The Golden Compass(1995, published as Northern Lights in the U.K.); and Will Parry, protagonist of the second book, The Subtle Knife (1997). The two move through a series of parallel universes, culminating in a visit to the kingdom of the dead and the realm of the Authority in the third book, The Amber Spyglass (2000)