“The one constant through all the years, Ray, has been baseball. America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game—it’s a part of our past, Ray. It reminds us of all that once was good, and that could be again. Oh, people will come, Ray. People will most definitely come.” (Field of Dreams)

“All that was once good, and that could be again” associates baseball not simply with nostalgia, but with what we might even in some moods call “sacred time.” Mircea Eliade, speaking of the importance of myth in ancient societies, says that “myth is thought to express the absolute truth, because it narrates a sacred history” (Eliade 23). The modern world, he continues, “is in quest of a new myth, which alone could enable it to draw upon fresh spiritual resources and renew its creative powers” (25). For true believers, baseball fills that void, and indeed, for Cubs fans the desire to reenter that “sacred history” has been a constant drive, season after season in a park that, more than any other stadium in the country, evokes a golden past, the “friendly confines” of beautiful Wrigley Field, with its ivy walls and storied history. We cherish memoirs of star players (autographed balls, bats, and the like) like the relics of saints. Eliade says that “in imitating the exemplary act of a god of mythic hero, or simply by recounting their adventures, [one]…detaches himself from profane time and magically re-enters the Great Time, the sacred time” (23). For Cubs fans, the baseball season at Wrigley is itself, in their hopes, the magical recreation of that sacred time, which for them has always been 1908.

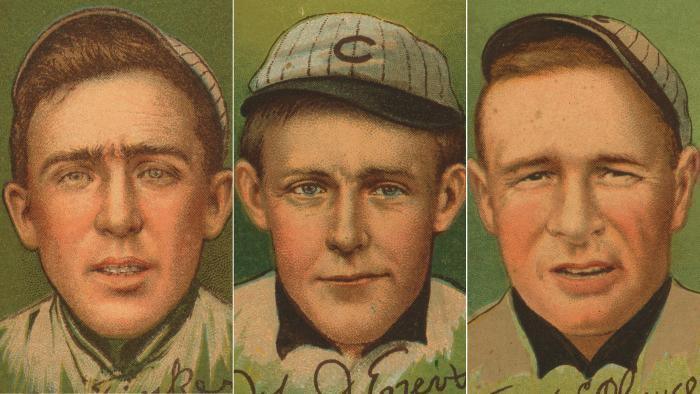

The Chicago Cubs were the first team in baseball history to win back-to-back world series in 1907 and 1908. Their famous double play combination, the heroes of that team, like the heroes of myth, have been immortalized in verse—in this case a lament from a New York Giants fan named Franklin Pierce Adams:

These are the saddest of possible words:

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

Trio of bear cubs, and fleeter than birds,

Tinker and Evers and Chance.

Ruthlessly pricking our gonfalon bubble,

Making a Giant hit into a double–

Words that are heavy with nothing but trouble:

“Tinker to Evers to Chance.”

It would be 108 years before the Cubs won another world series. That is the longest time between championships for any team in any major sport in history. After 1908, the Cubs were in world series in 1910, 1918, 1929, 1932, 1935, 1938, and 1945. They lost every one. After 1945, they would not be in another world series for 71 years. When the league expanded and split into divisions, changing the playoff format, the Cubs finally returned to the post-season after 39 years in 1984. They made the playoffs again in 1989, 1998, 2003, 2007, 2008, and 2015, but were never able to advance to the world series. But at the beginning of every season for 108 years, the Wrigley faithful came to the park or tuned in to WGN with the hope that springs eternal within the human breast.

Joseph L. Price wrote in 2006 that “For half a century, the faithfulness of Cubs’ fans and their refusal to concede the loss of hope have provided a cultural measure for the focus on the unrealizable ideal, a utopian event, a manifestation of a Kingdom which is not of this world” (202). Christians, Jews, and Muslims have all found theological inspiration in Cub fandom. Sister Ann Terese Reznicek, a nun in the Congregation of St. Joseph, declared that “Perseverance, loyalty, faithfulness, long-suffering—those are the things that we talk about in our lives, and those are the things we need when we cheer for the Cubs” (O’Connell). Ron Dermer, one-time Israeli ambassador to the U.S., suggested that “The Cubs might be the most Jewish team in America….They’ve experienced a long period of suffering, and now they’re hoping to get to the promised land” (Caron). And Rany Jazayerli, a baseball analyst and a Muslim, explained that “Sabr, or patience, is one of the defining traits that the Qu’ran exhorts Muslims to develop, stemming from a certainty that God will grant us relief from our afflictions, if not in this life then in the next one….Cubs fans seem to have mastered the concept. It will happen some day. If not in their lifetime, then in their children’s lifetime, or grandchildren’s” (Caron).

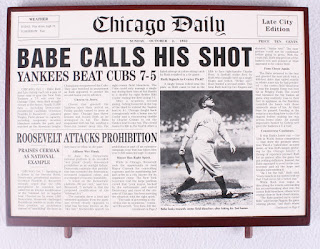

One of the questions all religions ask is, “Why is there suffering?” For Cubs fans, this was a question of very real significance for many decades. Baseball players and fans have always been superstitious, and there often seemed to be some supernatural reason for the Cubs’ failures. In game four of the 1929 world series, with the Cubs leading 8-0 in the 7th inning, Hall of Famer Hack Wilson lost a fly ball in the sun that resulted in a three-run inside the park home run that sparked a 10-run rally by the Philadelphia Athletics, who went on the win the series in five. It was like being smitten by heaven. In game three of the 1932 world series, Babe Ruth famously “called his shot,” pointing to the outfield bleachers and then hitting Cubs’ pitcher Charlie Root’s next pitch into the stands where he’d pointed.[1] After that bit of hocus pocus, the Yankees won the series in four straight.

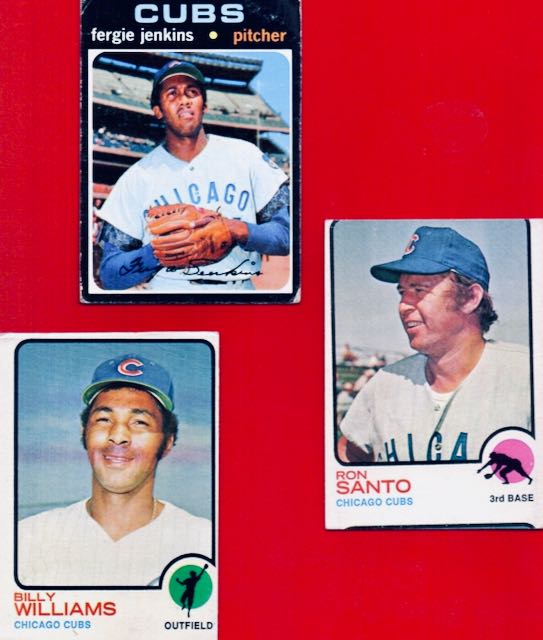

But the most notorious supernatural interference in Cubs history was the “Curse of the Billy Goat.” Cubs fan William Sianis, owner of the Billy Goat Tavern, had brought his goat Murphy to the fourth game of the 1945 series with Detroit, the first game at Wrigley, but when some other fans objected to the goat, Murphy and his owner were ejected, and Sianis reportedly pronounced the curse: “Them Cubs, they ain’t gonna win no more!” It was 71 years before the Cubs returned to the series. Some saw this curse as the reason for the Cubs’ famous collapse of 1969. That Cubs team, with a core of four future hall-of-famers (Ernie Banks, Billy Williams, Ron Santo and Fergusson Jenkins), known as “the greatest team that never won,” had a nine-game lead going into September but were ultimately caught and passed by the “Miracle Mets.”

Another manifestation of the Billy Goat curse was, supposedly, 2003. The Cubs led the National League Championship series against the Florida Marlins 3 games to 2, and were ahead 3-0 going into the eighth inning of game six. My son-in-law called me saying, “Dad, we’re gonna do it!” And I said, “Well, this is the Cubs. Let’s not celebrate yet.” And five outs from the World Series, Marlin Luis Castillo hit a fly ball into foul territory in left field. Cubs’ outfielder Moises Alou had a chance to catch the ball, but as he leaped to get it, Cub’s fan Steve Bartman tried to grab it from the stands, deflecting the ball and spoiling what would have been the second out.[2] The rest is history. The goat won again.

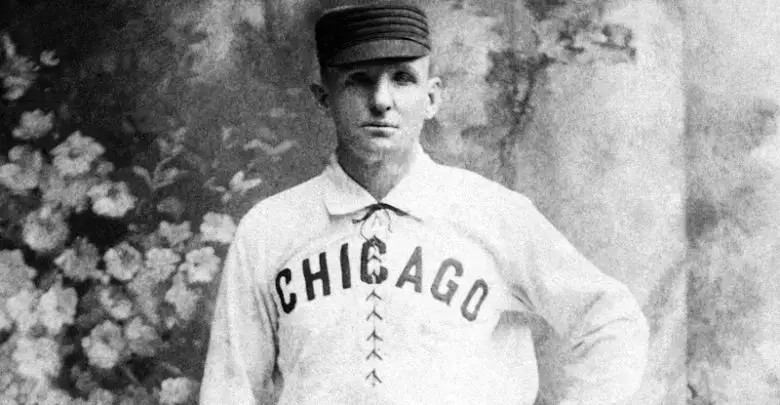

But how seriously can we really take the idea of a “curse”? A more rational theology demands accountability. When Israel fell off from Yahweh they suffered persecution and conquest from Assyrians and Babylonians. When Adam and Eve disobeyed God’s command, they doomed their descendants through original sin. Baseball’s original sin is the same as America’s as a nation: racism. Until 1947, African American players were barred from playing major league baseball. Why should the Cubs in particular suffer as a result of this sin? Perhaps because of Cap Anson. Anson was the undisputed greatest player of the nineteenth century. He was the first player to get 3000 hits. He batted over .300 twenty times. And as player-manager he led the Cubs franchise (then called the White Stockings) to five championships in the early decades of the National League. But he is thought to be the chief reason black players were excluded from the sport. As manager he is reputed to have stated that he would never step on a field with a Black player. In 1887, he did refuse to let his team play an exhibition game against a Newark team that had an all-Black battery of Moses Fleetwood Walker and George Stovey (“Cap Anson”). From that point on, baseball owners and managers shared a “gentleman’s agreement” to keep black players out of major league baseball.

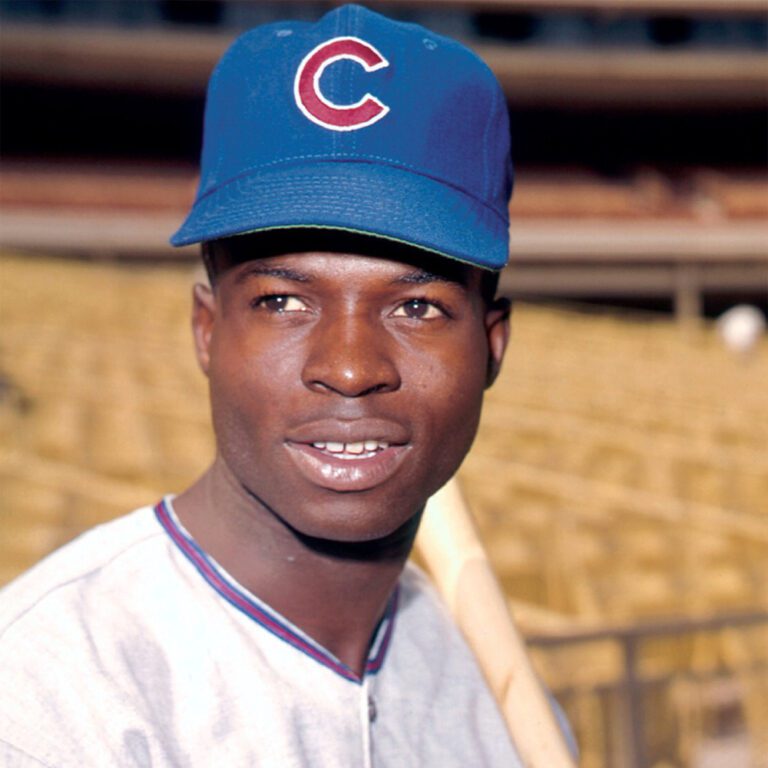

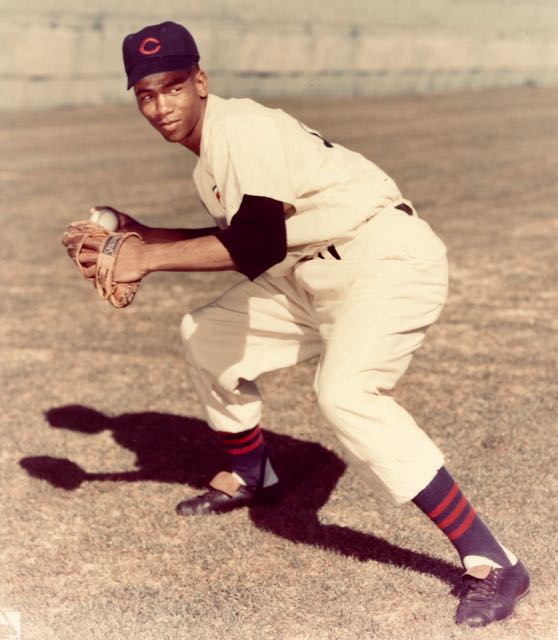

Long-time owner P.K. Wrigley was famously reluctant to integrate his team. Even after the Cubs integrated in 1954 with shortstop Ernie Banks, who became the most popular Cubs player of all time, earning the title “Mr. Cub,” there is still evidence that owners and management remained essentially racist. In 1964, the Cubs had Banks, Billy Williams, and first baseman George Altman on the field, and as a fourth starter an up-and-coming new left fielder named Lou Brock, which would make half of their starting line-up African-American. When Negro-league veteran and Cubs coach Buck O’Niell heard that management planned to trade Brock, he complained to John Holland, the general manager. According to O’Niell, Holland then “Started pulling out letters and notes from people, season ticket holders, saying that their grandfather had season tickets here at Wrigley Field…and their families had come here for years. And do you know what these letters went on to say? ‘What are you trying to make the Chicago Cubs into? The Kansas City Monarchs?’” (qtd. in Bogira). The Cubs traded Brock to Saint Louis in mid-season for pitcher Ernie Broglio in what is universally regarded as the worst trade in team history. Brock went on to spark the Cardinals to the world series championship in 1964 and again in 1967 en route to a hall of fame career that included 3000 hits and, at the time of his retirement, the all-time record for stolen bases. Broglio won a total of seven games for the Cubs over a span of three years, then retired. This was not a curse. It was just racism.

And the racism was just one facet of all around poor management. The Wrigley family were simply too cheap to field a winning team. Throughout the ‘50s they seemed to think that since people would come out to see Ernie Banks, they didn’t need to bother to provide him with some team mates that might help him win. Nor did they ever pay Banks what he was worth, even by the standards of the time. After his second consecutive MVP season in 1959, they raised his salary to $50,000, and the most he ever made was $60,000, which was less than half of what Willie Mays and other star players were making. The Wrigleys also never put money into modernizing Wrigley Field, and that included putting in lights. The biggest reason for the Cubs famous 1969 collapse was the fact that the team had to play all its home games under the hot sun of the Chicago summer. By September, they were worn out. Billy Williams, who played a National League record 1,117 consecutive games, was exhausted by the season’s end. It wasn’t the Billy Goat that jinxed the 1969 club, or the black cat that Mets fans sent out on the field during the crucial series in New York. It was the Wrigleys’ avarice.

The Tribune company finally bought the team in 1981, and began to try to correct decades of bad management, and lights were finally installed at Wrigley in 1988—forty years after every other stadium in baseball had them. And now the Cubs were making it to the post season but still unable to push all the way.

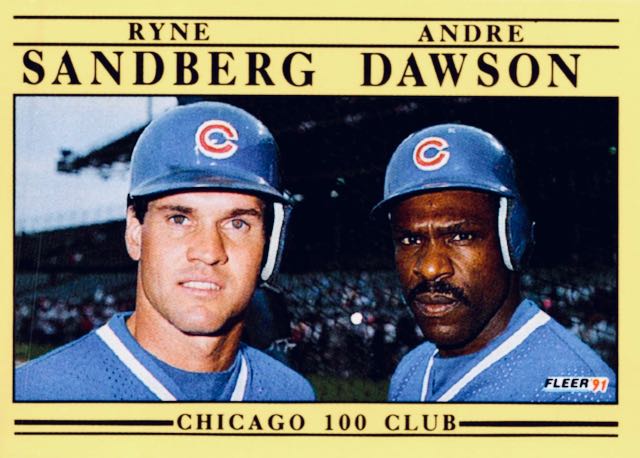

But it’s important to remember that there is also an ethical component to religion, and thus also to the religion of baseball. When Ryne Sandberg was inducted into the Hall of Fame in 2005, he talked about playing baseball with “respect for the game,” and extolled his teammate Andre Dawson for playing the game “the right way”: “The game fit me because it was right. It was all about doing things right. If you played the game the right way, played the game for the team, good things would happen” (Sandberg).

It wasn’t hard to read between the lines. During the late ‘90s and the early 2000s, the Cubs were powered largely by superstar Sammy Sosa, the only player in the history of baseball to have three seasons with more than 60 home runs. And by 2005 everybody knew those home runs were powered by steroids—like Barry Bonds’ and like Roger Clemens’ fast ball. Sosa had hit 40 home runs for the Cubs in 2003. Steve Bartman didn’t jinx the Cubs in that Marlins series. If they were jinxed, it was by their reliance on players who did not play the game the right way.

Finally, once more under new ownership (Tom Ricketts this time) dedicated to bringing a world championship to the north side, the Cubs hired the management team that had ended the Boston Red Sox’ championship drought and that was dedicated to doing things the right way. The hopes of the Cubbie faithful were finally realized in 2016. When Kris Bryant fielded that last ground ball and threw it to Anthony Rizzo for the final out of game seven in Cleveland, I wept openly. I was thinking of my father, who died in 2005 at the age of 86. He’d been a Cubs fan all his life and had never seen them win a world series.

In the film Bull Durham, Annie Savoy (whose religion is baseball), notes that there are 108 beads in a rosary, and there are 108 stitches in a baseball.[3] Can it possibly be a coincidence that the Cubs’ World Series victory in 2016 occurred exactly 108 years after their last championship? I don’t think so.

Works Cited

Adams, Franklin Pierce. “Baseball’s Sad Lexicon.” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems/46679/baseballs-sad-lexicon. Accessed 18 April 2023.

Bogira, Steve. “Unfriendly Confines: Did Racial Discrimination Start the Cubs’ Slide?” Chicago Reader, 24 March 2014, https://chicagoreader.com/news-politics/unfriendly-confines-did-racial-discrimination-start-the-cubs-slide/. Accessed 18 April 2023.

Bull Durham. Written and directed by Ron Shelton, performance by Susan Sarandon, Orion Pictures, 1988.

“Cap Anson.” National Baseball Hall of Fame, https://baseballhall.org/hall-of-famers/anson-cap. Accessed 18 April 2023.

Caron, Paul L. “Chicago Cubs Unite Jews, Christians and Muslims Who Identify With 108-year Exile.” TaxProf Blog, 30 October 2016, https://taxprof.typepad.com/taxprof_blog/2016/10/chicago-cubs-unite-jews-christians-and-muslims-who-identify-with-108-year-exile.html. Accessed 18 April 2023.

Eliade, Mircea. Myths, Dreams, and Mysteries: The Encounter between Contemporary Faiths and Archaic Realities. Translated by Philip Mairet, Harper & Row, 1957.

Field of Dreams. Written by W.P Kinsella and Phil Alden Robinson, directed by Phil Alden Robinson, performance by James Earl Jones, Universal Pictures, 1989.

O’Connell, Patrick M. “For Many, Baseball Can Be a Leap of Faith.” Chicago Tribune Digital Edition, https://digitaledition.chicagotribune.com/tribune/article_popover.aspx?guid=91299188-2933-442b-8418-28d09fb93804, Accessed 18 April 2023.

Price, Joseph L. Rounding the Bases: Baseball and Religion in America. Mercer University Press, 2006.

Sandberg, Ryne Dee. “Baseball Hall of Fame Induction Speech: Respect the Game Above All Else.” 31 July 2005. America Rhetoric, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/rynesandbergbaseballhalloffame.htm. Accessed 18 April 2023.

[1] Most historians of baseball believe this to be a myth. Yes, Ruth did point. But it seems unlikely he was implying he’d hit the next pitch out, But it makes for an effective legend.

[2] Again, people who have objectively looked at the video of this generally believe that Alou could not possibly have caught the ball. But his angry reaction got the sympathy of the crowd.

[3] Actually, there are 59 beads on a catholic rosary. But it turns out there are 108 on a Hindu one. There are 216 single stitches on a baseball, but there are 108 double stitches.