Buy Cheap Tramadol Online Uk Okay, so when I say that I’m naming Tim O’Brien’s The Things They Carried as book number 65 (alphabetically) on my list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language,” I can hear you saying “But wait Jay Ruud, how can you do such a thing? Your list says ‘Most Lovable Novels.’ This book doesn’t fit the category ‘novel,’ does it? It’s a collection of short stories! I call foul, sir!”

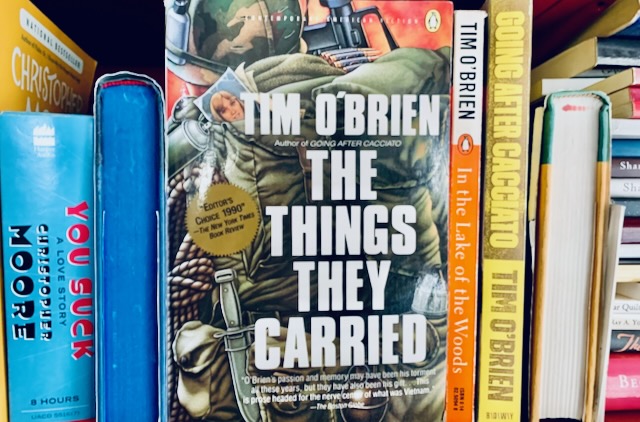

To which I respond, “Hey, if I wanna include all prose fiction under the umbrella of ‘novel,’ that’s what I will do. Because it’s my list, dammit.” And there’s a good chance there will be other short story collections on this list. I considered Hawthorne’s Twice Told Tales, Joyce’s Dubliners, Hemingway’s In Our Time, and Faulkner’s Go Down Moses before selecting other works by those authors. And I considered including Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, and a couple of Alice Munro’s collections, but ultimately decided I loved other fictional works more. Tim O’Brien is also a novelist, of course, having written the Vietnam War novel Going After Cacciato in 1978, for which he won the National Book Award. But for me it was O’Brien’s 1990 collection of linked stories, The Things They Carried, that tells the Vietnam War story more memorably and more truly yet artistically than any other book out there. And it’s the most lovable too.

O’Brien’s book sold more than two million copies in its first eighteen months, and continues to be read, and taught, in college courses and in high schools as well, much to O’Brien’s own amazement. It was a finalist for the 1990 Pulitzer Prize and for the National Book Critics Circle Award. It won neither, but did win France’s Prix du Meilleur Livre Étranger Award. In 2014, Amazon came out with a list of “100 Books to Read in a Lifetime,” on which they included The Things They Carried. In 2016, the Library of Congress created an “America Reads” exhibit honoring 65 books chosen by the public as “the most influential books written and read in America and their impact on our lives,” which included O’Brien’s book. On Goodread’s “Listopia” list of more than 1600 “Greatest War Novels of All time,” The Things We Carried came in at number 3—just after All Quiet on the Western Front and Catch-22. And on the site “Shortform,” whose creators say that their purpose is to “make sense of information,” there is a list of the 100 best books of war fiction ever, O’Brien’ book comes in as number 1.

Like so many books on this list, The Things They Carried is semi-autobiographical, and it reads much like a memoir, so that its raw reality causes many readers to lose track of the fact that it is fiction. Its narrator’s name is Tim O’Brien, so the other men in O’Brien’s Alpha Company platoon seem real as well, especially when O’Brien dedicates the book to those men. But, though based as they may be on men O’Brien knew, they, like the narrator, are fictional. One of the themes of the book is the difference between truth and fiction, and the fact that the truth is sometimes better served when presented in a work of fiction. Most of O’Brien’s readers would agree that this book illustrates that point vividly.

O’Brien served in Vietnam from 1969 to 1970, and the book comprises a collection of linked stories about the war and its aftermath for the members of Alpha company. Individual soldiers are introduced in the book’s title story, which acts as a kind of overture to the rest of the stories, each of which speaks about the experience of one of these men, and characters who appear as minor characters in one story will turn up as protagonists in another, so that while each story can stand on its own, they all augment and complement the others. Clearly I can’t discuss each story in the book, so for this review I’ll just single out the four that strike me as most important or interesting or thematically significant.

The first story, providing the framework of the book, actually does create Vietnam—or at least the experience of an American GI in Vietnam—in a very palpable way, by discussing the specific items each man carries in his pack. How much does each item weigh? Which items are standard issue and which are personal, and what is the weight—physical and emotional, of those personal items? Soldiers carry pocketknives, matches, can openers, sewing kits and C rations. Most carry M-16 assault rifles but others carry M-60 machine guns or M-79 grenade launchers. Henry Dobbins carries his girlfriend’s pantyhose around his neck for luck. Ted Lavender carries tranquilizers and marijuana for his nerves. Kiowa carries a New Testament that his father gave him, as well as his grandfather’s hunting hatchet. Norman Bowker carries a diary. All of the men carry “grief, terror, love, longing” as well as “shameful memories’” and “the common secret of cowardice.” That latter burden is akin to “the soldier’s greatest fear, which was the fear of blushing. Men killed, and died, because they were embarrassed not to.” On top of all this, O’Brien says, “they carried ghosts.” The platoon’s lieutenant, Jimmy Cross, carries letters and photographs of Martha, a girl back in New Jersey who shows no sign of returning his love. When Lavender dies near the village of Than Khe, Cross believes it is because he’d been distracted by thoughts of Martha, and the following day he burns his relics of Martha and determines to take the blame for Lavender’s death in front of the rest of his men. This responsibility is something he will continue to carry with him, “like a stone in his stomach,” from that time on.

The story entitled “How to Tell a True War Story” is particularly evocative because it brings to the fore ideas that Tim O’Brien the author is dealing with himself as he tries to create a book that tells the truth about the Vietnam experience. In this story, he explores various attempts by members of his company to tell the story of how one of the platoon, Curt Lemon, actually died. Truth is complex, for sure. Truth may involve invention used to create, for the listener, a sense of the emotional truth of a thing, or to render believable something that may otherwise seem fantastic. O’Brien opens the story by saying “This is true.” Then he proceeds to tell how the company medic, “Rat” Kiley, wrote a letter to Curt Lemon’s sister, telling her what a hero her brother was and how he had loved him. O’Brien tells us, however, that Lemon had died when he and Kiley were playing catch with a smoke grenade, and Lemon stepped from the shade of trees into the sunlight and inadvertently was blown up by stepping on a rigged live mortar shell. Kiley is angry when the sister never writes back, and subsequently, channeling his rage at the death of his friend (and the sister’s failure to respond), Kiley repeatedly shoots a water buffalo until two of his fellow soldiers remove the carcass and throw it in the water. O’Brien relates a story told by another of his company, Mitchell Sanders, who tells of a troop in the mountains who hear strange voices and music, and order air strikes on the area. When everything in the area is destroyed, they still hear the noises, and escape down the mountain. The next day Mitchell tells O’Brien that he made up some parts of the story, but mainly wanted to stress silence as the tale’s moral. The point sems to be that, in a true war story, nothing is absolutelytrue. The narrator remembers climbing the tree under which Lemon died in order to throw down parts of the dead man’s body, while his platoon mate Jensen sang “Lemon Tree.” And finally, O’Brien himself remembers witnessing Lemon’s death, and imagines that Lemon must have believed it was the sun that was killing him. He wishes he could get the story right, the truth of “how the sun seemed to gather around him and pick him up and lift him high into a tree.” Throughout the story, O’Brien makes statements about what a true war story is and is not:

A true war story is never moral. It does not instruct, nor encourage virtue, nor suggest models of proper human behavior, nor restrain men from doing the things men have always done…In any war story, but especially a true one, it’s difficult to separate what happened from what seemed to happen….You can tell a true war story by the way it never seems to end. Not then, not ever….True war stories do not generalize. They do not indulge in abstraction or analysis….Often in a true war story there is not even a point, or else the point doesn’t hit you until twenty years later, in your sleep, and you wake up and shake your wife and start telling the story to her, except when you get to the end you’ve forgotten the point again….And in the end, of course, a true war story is never about war. It’s about sunlight. It’s about the special way that dawn spreads out on a river when you know you must cross the river and march into the mountains and do things you are afraid to do. It’s about love and memory. It’s about sorrow. It’s about sisters who never write back and people who never listen.

The death of the popular and compassionate soldier Kiowa is explored in several stories in the book. In a way it is the climax of the war experience of Alpha company. Of these stories, the most significant is “Speaking of Courage”: having explored the nature of truth, O’Brien now takes on that other great abstraction associated with war—courage. The protagonist of “Speaking of Courage” is Norman Bowker, who, having returned to his hometown in Iowa after the war, is haunted by Kiowa’s death and his own failure of nerve that he believes led to Kiowa’s death. Bowker, O’Brien tells us, “had been braver than he ever thought possible, but . . . he had not been so brave as he wanted to be.” Upon his return to Iowa, Bowker finds his best friend dead and his ex-girlfriend married, and on the Fourth of July he drives his father’s car around the lake where his best friend drowned, having nowhere in particular to go. He’s thinking about his father, who had been proud of him for bringing back seven medals from the war (including a Bronze Star and a Purple Heart). But Norman cannot help imagining what it would be like telling his father how he almost won the Silver Star. He recalls how the platoon camped one night along a river, but realized too late as the rain poured down that they had in fact camped in the nearby village’s sewage field. When mortar shells began to hit the camp, the field itself began to boil as if turned to quicksand, and Bowker heard Kiowa scream as he began to sink into the sewage and muck. Bowker had held onto Kiowa’s boot, but ultimately had to let him go to save himself from sinking into what O’Brien calls the “shit field”—a not exactly subtle metaphor for the Vietnam war itself. In a postscript to the story, O’Brien reveals that after the war Bowker had come to him and asked hm to write the story of the missed Silver Star—but three years later had hanged himself with a jump rope in the YMCA. Significantly, O’Brien has been able to process his trauma by working through his experiences in language and story. Bowker, without anyone to talk to, saw no way out of his mental suffering.

The fourth and, for me, the most memorable story in the book, comes early in the text and might be called a “pre-Vietnam” story, “On the Rainy River.” The story is one of the least “true” in the usual sense of the word, since the “Tim O’Brien” of the story engages in behavior that the author never did. The fictional O’Brien is drafted upon finishing college in 1968. His attitude toward the war—which probably reflects the author’s own—is “that you don’t make war without knowing why. Knowledge, of course, is always imperfect, but it seemed to me that when a nation goes to war it must have reasonable confidence in the justice and imperative of its cause. You can’t fix your mistakes. Once people are dead, you can’t make them undead.” And so O’Brien plays with the idea of going to Canada. He is quite certain that this is the absolute right thing to do from a moral perspective. He drives from his home in Worthington, Minnesota up to the Rainy River on the Canadian border. He stays at a lodge with an old man who takes him fishing very close to the Canadian side, where all he has to do is jump from the boat to be safe in Canada. But in the end, he cannot take that final moral step. What prevents him from jumping is precisely what the narrator says in the opening story: men fought and died because they were embarrassed not to. “I did not want people to think badly of me,” our protagonist says here. “Not my parents, not my brother and sister, not even the folks down at the Gobbler Café. I was ashamed to be there at the Tip Top Lodge. I was ashamed of my conscience, ashamed to be doing the right thing.” At the end of the story, the narrator, in an ironic twist that completely reverses common expectations, says he returned home, was drafted, went to Vietnam and returned. “I survived, but it’s not a happy ending,” he concludes. “I was a coward. I went to the war.”

These themes—truth, courage, and morality—are, being abstractions, all things that O’Brien says true war stories are never about. However, there is always some part of a true war story that is not absolutely true, and that dictum may be one of the untrue things about this story collection. At least one of the chief things a reader takes away from these stories is the sense that such things as truth, courage and morality are not clear cut, perhaps are even turned on their heads, in the reality of the U.S. war in Vietnam.