When most readers think of Vladimir Nabokov, the Russian émigré author who came to the U.S. to teach Russian at Cornell University and began to write novels in English, they think most often of his 1955 novel Lolita, which was a huge best seller and ranked number four on the Modern Library list of the 100 greatest English language novels of the 20thcentury. Lolita was chosen by Penguin classics readers as number 52 on their list of 100 “Must Read Classics,” and appears as well on the Time magazine list of the 100 greatest English language novels since 1923, as well as the Guardian list of best novels in English, the Observer list of the best world novels, and the Norwegian book club list of the best world novels. That’s a lot of lists.

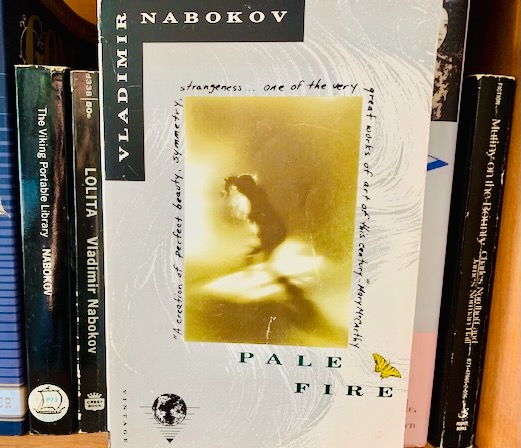

But it doesn’t appear on mine. The fact is, I really don’t love Lolita. Sure, it’s a remarkable study of a narrator’s obsession, but I find it hard to empathize with Humbert Humbert. Or his obsession Lolita either. But Lolita made Nabokov independently wealthy—wealthy enough to quit teaching and return to Western Europe, where he wrote his next novel, Pale Fire, beginning it in Nice in 1960 and completing it in Montreux, Switzerland in 1961. Pale Fire is not as widely admired as Lolita, though it does appear on both the Modern Library and the Time magazine list of 100 great English language novels of the 20th century, and is listed as number one on critic Larry McCaffery’s “20th Century’s Greatest Hits: 100 English-Language Books of Fiction”—a list he compiled in direct response to the famous Modern Library list. In fact, Pale Fire is truly a more original, a more interesting and a more important novel, and, to my mind, a much more lovable one than Lolita. And so it’s Pale Fire that appears as number 64 (alphabetically) on my list of the “100 Most Lovable Novels in the English Language.”

One of the reasons for this importance is the radical new structure Nabokov employed in the novel. When the book was published in 1962, a lot of readers and critics did not understand this new form, or realize that Nabokov had created one of first post-modern novels in our literature. And it was the financial success of Lolita that allowed Nabokov to take the chance of writing this highly experimental book.

Essentially the novel consists of a 999-line poem in four cantos of heroic couplets entitled “Pale Fire” and purported to be written by John Shade, a fictional poet presented in the novel as a well-known academic American poet, and “Pale Fire” is presented as his final poem. The poem’s title is an allusion to Shakespeare’s Timon of Athens (Act IV, scene 3): “The moon’s an arrant thief, / And her pale fire she snatches from the sun,” a line often interpreted as depicting the process of poetic inspiration. And this, no doubt, is what the fictional Shade intended by the title.

Nabokov, however, has other ideas. For the book itself is not simply the poem. Nabokov presents the book as a scholarly edition of the poem: Charles Kinbote, a neighbor of Shade and a colleague from Wordsmith College in the New England town of New Wye, writes a line-by-line commentary on the poem as part of the critical apparatus of the text, along with an introduction and an index/glossary. But once you begin reading the commentary, you will become quite confused, since Kinbote’s interpretations and glosses on the text seem to be wildly inaccurate readings of Shade’s lines (thus Kinbote may be the thieving “moon” of Shakespeare’s quotation, stealing the light of Shade’s “sun”).

Reading Kinbote’s “Foreword” ought to prepare you for this rude shock, however. There you learn that upon the recent sudden death of the poet, Kinbote has come into possession of the manuscript of Shade’s just-completed poem (a hand-written manuscript on 80 medium-sized note cards), and has taken advantage of Shade’s grieving widow Sybil by getting her to sign a contract giving him complete control over the editing and publication of Shade’s final poem. But when the academics of the Wordsmith English department hear of this they quickly convince Sybil to renege on this promise, since Kinbote is not in the least qualified to engage in such an undertaking. And so despite the objections of the poet’s widow, his department, and reputable scholars of the poet’s work, Kinbote has absconded with the manuscript, hunkering down with it in some “tumble-down ranch” in a fictional location in the Northwest (“Utana”) where he goes about preparing his edition.

Shade’s poem is a kind of verse autobiography, a kind of Wordsworthian Prelude but in a more Popean and mocking Neoclassical tone and occasionally Elliot-like diction and structure (Shade’s four cantos alluding, perhaps, to the Four Quartets? Or even Pound’s Cantos?). In any case, Nabokov seems to imply a canon-like, if somewhat old-fashioned, quality to Shade’s poetic legacy. The first canto focuses on Shade’s early life, in particular his experiences of death and with what he regarded as the supernatural. Canto two, perhaps the most moving part of the poem, recounts Shade’s family life and the life of his young daughter Hazel, who died by suicide. In canto three, Shade describes his quest, following Hazel’s death, for evidence of an afterlife, which ends in ironic disappointment, but disappointment that turns to what he calls a “faint hope.” The final canto gives an account of Shade’s creative process and of his belief in poetry and the process that produces it as a means of finding meaning in the world after all.

Some critics have found Shade’s poem a kind of travesty, little short of doggerel. Others, myself included, have found it to be moving and profound in parts. Paul Muldoon, poetry editor of the New Yorker, said “I do think ‘Pale Fire’ is a quite wonderful poem, though it’s hard to read it as an entirely discrete entity.” That is to say, one must read it in context to fully experience the poem.

And that context includes the Kinbote commentary, a commentary that the reader very quickly realizes has almost nothing to do with the actual poem. Kinbote, apparently a delusional megalomaniac, describes how he and his neighbor Shade would go for evening walks, and how he, Kinbote, aware that Shade was working on a major new poem, would spend these walks relating the sad story of the last king of Kinbote’s own “distant northern land” of Zembla, King Charles II (“The Beloved”), a king deposed after a Soviet-inspired revolution, who was able to escape his palace through a secret passage and to get out of his country in disguise, with the help of brave loyalists risking their own lives for him. (Of course, the story is inspired by popular rumors about the escape of the Romanov princess Anastasia from Bolshevik executioners in 1918). Imagine Kinbote’s disappointment when, upon reading Shade’s text, he finds not a single mention of Zembla’s fugitive king.

Yet Kinbote seems ultimately to have convinced himself that Shade’s poem, contrary to its apparent subject, is in reality a poem secretly encoding the story of Zembla’s last king, and sets out, in his commentary, to decipher Shade’s vast network of allusions. This becomes apparent early on, when in “explanation” of a brief phrase of Shade’s, Kinbote introduces the entire history of his deposed king:

Line 12: that crystal land

Perhaps an allusion to Zembla, my dear country. After this, in the disjointed, half-obliterated draft which I am not at all sure I have deciphered properly:

Ah, I must not forget to say something

That my friend told me of a certain king.

Alas, he would have said a great deal more if a domestic anti-Karlist [Kinbote is convinced that the chief reason Shade had left out explicit references to the Zemblan king was that Sybil disliked Kinbote and convinced Shade to excise any mention of his pet theme] had not controlled every line he communicated to her! Many a time have I rebuked him in bantering fashion: “You really should promise to use all this wonderful stuff, you bad gray poet, you!” And we would both giggle like boys. But then, after the inspiring evening stroll, we had to part, and grim night lifted the drawbridge between his impregnable fortress and my humble home.

That King’s reign (1936-1958) will be remembered by at least a few discerning historians as a peaceful and elegant one…

And on and on goes the commentator, describing in some detail King Charles’ reign. Gradually, it becomes apparent to the reader that Kinbote is actually the king himself, in hiding here as a professor of foreign languages at Wordsmith College. He introduces, as well, immediately after this apparent digression in the Shade commentary (but what is absolutely central to the Kinbote story) an even more tangential note on another phrase:

Line 17: And then the gradual…

By an extraordinary coincidence (inherent perhaps in the contrapuntal nature of Shade’s art) our poet seems to name here (gradual, gray) a man, whom he was to see for one fatal moment three weeks later, but of whose existence at the time (July 2) he could not have known. Jakob Gradus called himself variously Jack Degree or Jacques de Grey, or James de Gray…

And Kinbote goes on at length to introduce this shady Grey character, who we eventually realize is an agent of the revolutionary government of Zembla who had been tasked with tracking down and assassinating the escaped King. When we consider that Kinbote himself is the incognito King Charles, or at least believes himself to be, we realize that ultimately Gradus, tasked with the job of slaying King Charles/Kinbote, instead accidentally gunned down Shade while the two neighbors were out on one of their evening walks (In fact there is an eerie echo here of the death of Nabokov’s own father, who was killed by someone who meant to kill somebody else).

At least this is one possibility. Indeed, Nabokov’s novel might be seen as the author’s reasoned response to the school of literary theory known as “Reader-Response Criticism,” made popular beginning in the late 1960s and 70s by such scholars as Stanley Fish, Norman Holland, and Wolfgang Iser. It’s a school of criticism that elevates the role of the reader or audience in bringing real existence to a particular work of art by the act of reading and interpreting it so as to create a meaning—sometimes a highly subjective or uniquely individual one—to a particular literary text. In some respects, Pale Fire is a reductio ad absurdum of Reader-Response Theory. But at the same time, Nabokov has deliberately included hint after hint, in Kinbote’s text especially, of “Easter eggs”—possible conflicting interpretations of the novel that various readers can, and do, pick up and run with.

For example, Kinbote may be the King of Zembla. Or he may be insane and only believe he is the King of Zembla. Or he may be delusional and neither King Charles nor Zembla itself really exist. Gradus may be an agent sent to assassinate him, or he may be a random mugger who happens to shoot Shade, or someone disgruntled somehow with Shade the poet or Shade the college instructor and come to exact revenge. Or Kinbote may not exist at all, but be a fictional creation of John Shade’s who actually composed the entire book. Several critics have suggested that Kinbote is in fact the alter-ego of Wordsmith Professor V. Botkin or Botkine, described in Kinbote’s index as “an American scholar of Russian descent” (note that “Botkine” is an anagram of “Kinbote”), an insane ex-professor who imagines himself to be this Kinbote, ex-king of Zembla, and that Kinbote and Zembla exist only in Botkin’s mind. Clearly one of the “lovable” things about this novel is that it invites reading and reading again, and the discovery of new wrinkles in interpretation with every rereading.

Pale Fire came out in 1962 to mixed reviews, with one critic calling the book “unreadable” and another a “total wreck.” But novelist Mary McCarthy gave it a rave review, as did Clockwork Orange author Anthony Burgess, and Harold Bloom called it “a remarkable tour de force” and clear evidence of Nabokov’s genius. In fact, what most critics did not know quite what to respond to was the fact that this novel is one of the most significant examples of what would come to be known as “post-modernism”—akin in that way to other books on my list like Catch-22 and The Sot-Weed Factor. The multiplicity of possible interpretations of the text—the indeterminacy of the novel’s meaning—is one characteristic of the post-modern. It’s also an example of the postmodern staple metafiction—a form of fiction emphasizing its own fictionality so that the readers are never unaware that they are perusing a fictional text. The novel also encourages an interactive reading process, a post-modern technique known as hypertext that, like an electronic text, may be read straight through, or by jumping between Shade’s lines and Kinbote’s commentary on them.

All of these innovative techniques make Pale Fire a revolutionary and incredibly influential novel, and one that deserves to be on my exclusive list. Besides, it’s just so darn funny it’s hard to resist.