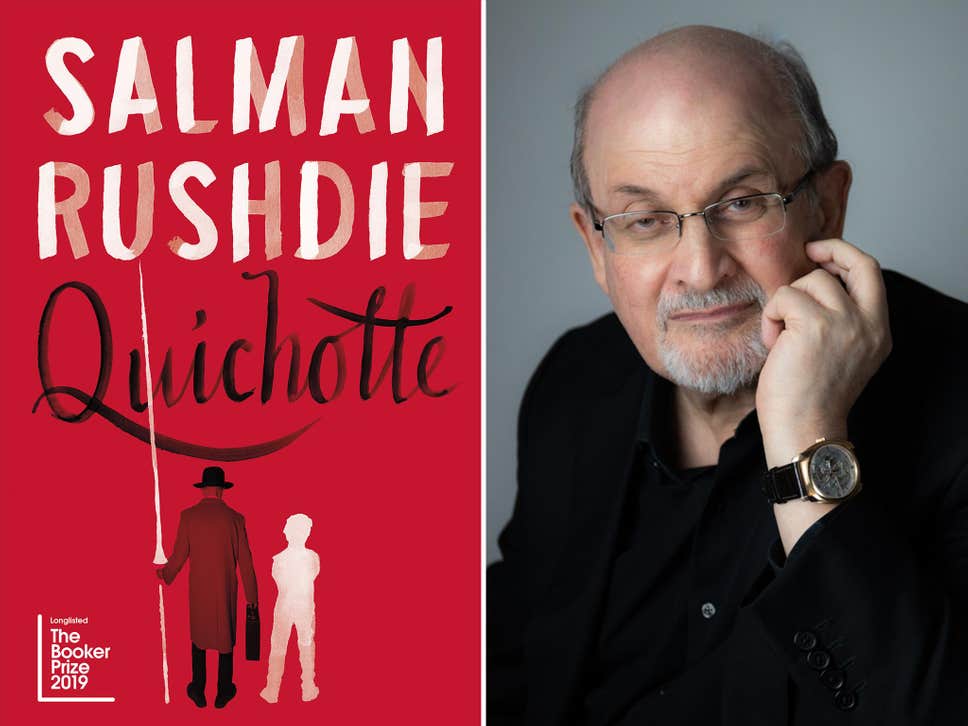

Quichotte

Salman Rushdie (2019)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Ruud Rating

4 Shakespeares

[/av_image]

Salman Rushdie’s latest novel, Quichotte, was published in the United States on September 3, following an August 29 release in the United Kingdom and in India. His first novel, Midnight’s Children, won the coveted Booker Prize in 1981, and his fourth, The Satanic Verses, made him the object of a fatwa issued by the Ayatollah Khomeini in 1989, placing him in danger of assassination and making him the most famous writer in the world, and the living symbol of the principle of freedom of speech. Does he still have the same talent for inciting controversy or inspiring strong emotions? His fourteenth novel, Quichotte, just shortlisted for this year’s Booker Prize, suggests that he does.

Despite strong initial reviews, Rushdie’s new novel, based in part on Cervantes’ immortal prototype of the picaresque novel (“Quichotte” is the French version of the Spanish Don Quixote, and references Jules Massenet’s 1910 opera Don Quichotte), the book has already garnered some mixed or even negative responses from respectable reviewers: Leo Robson, writing in The New Statesman, regarded Quichote as a “draining” novel and complained that “We’re simply stuck with an author prone to lapses in tact and taste, and a lack of respect for the reader’s time or powers of concentration.” Johanna Thomas-Corr, writing for The Guardian, said that “The novelist’s natural bent has always been towards the encyclopedic, but now he has graduated from encyclopedia to Google. Quichotte ends up suffering from a kind of internetitis, Rushdie swollen with the junk culture he intended to critique.” And Ron Charles at the Washington Post opined that “Rushdie’s style once unfurled with hypnotic elegance, but here it’s become a fire hose of brainy gags and literary allusions — tremendously clever but frequently tedious.”

I suppose I can see where these critics are coming from, but I found the book delightful, and the complexities they complain about wildly entertaining. I wonder if these critics have ever actually read Cervantes’ huge, episodic, meandering opus, whose protagonist wanders for a thousand pages across baroque Spain, encountering an encyclopedic plethora of characters and experiences, setting the pattern for the picaresque novel followed so beautifully by Rushdie. Or if they are unfamiliar with the post-modern absurd novel that characterized fiction of the sixties and seventies through such mammoth, meandering tomes as John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor or Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow. It may be that these readers think of such efforts as passé, relics of a different era, but if there was ever a time to look at American (and British, and Indian) society and recognize the absurd, this is it.

But Rushdie is quite familiar with Cervantes, and while he doesn’t follow the Spanish master’s plot episode by episode, like Joyce’s Ulysses with the Odyssey, he never loses sight of the spirit of Cervantes’ hero. He has discussed his inspiration in a recent interview, stating “Don Quixote is astonishingly modern, even postmodern—a novel whose characters know they are being written about and have opinions on the writing. I wanted my book to have a parallel storyline about my characters’ creator and his life, and then slowly to show how the two stories, the two narrative lines, become one.” And this he does, introducing readers shortly into his opus to a middling writer of spy fiction with the pen name of Sam DuChamp, who has self-reflexively created Quichotte, the contemporary Quixote, to examine his own life as well as the contemporary world, just as Cervantes satirized his own society. These goals result in precisely the kind of sprawling behemoth of a novel Rushhdie has produced: “So many of today’s stories are and must be of this plural, sprawling kind,” he says in the book, “because a kind of nuclear fission has taken place in human lives and relations.” Thus what we see in Quichotte is an America, and a Britain, that because of constant media bombardment in this “information age” are completely unable now to tell the difference between truth and lies. The world, he says, “has become so accustomed to wearing its masks that it has grown blind to what lies beneath.”

Quichotte begins with a scene amusingly parodying Quixote. As Cervantes’ hero went mad by reading too many chivalric romances, Ismail Smile, an elderly former pharmaceutical salesman, his brains addled by his obsession with watching everything he possibly can on television (and with an apparent inability to sift through all the chaff for kernels of truth or value), ultimately sees himself as the hero of his own story, and decides to rename himself “Quichotte” and set off on a quest that will take him across the country to New York City, where he will unite with his true angelic Dulcinea, a TV talk show hostess (conceived as “Oprah 2.0”) named Salma R., a South Asian-American born, like himself, in the city they still think of as “Bombay.” Along the way, Quichotte also imagines into being a son that he never had, a son he names Sancho who is to be, he says, “My son, my sidekick, my squire! Hutch to my Starsky, Spock to my Kirk, Scully to my Mulder, BJ to my Hawkeye, Robin to my Batman! Peele to my Key, Stimpy to my Ren, Niles to my Frazier, Arya to my Hound! Peggy to my Don, Jesse to my Walter, Tubbs to my Crockett, I love you!” This sort of over-the-top, endless plethora of pop culture references is what some of those negative reviewers are objecting to, but the purpose of Quichotte’s story, we are told by its author, is “to take on the destructive, mind-numbing junk culture of his time just as Cervantes had gone to war with the junk culture of his own age.” And this is what the book does, ad absurdem. But this is not a flaw. The bombardment of detail is the realization in print of a culture that does not separate truth from falsehood: Form matches content.

Behind this, of course, we also follow the life of Quichotte’s author DuChamp, who seems to be exorcizing his own demons through Quichote’s parallel life: like his character, DuChamp goes by an assumed name, was born in Bombay, sets out on his own quest to restore relationships with his estranged son—who in a nod to his father and to the spirit of Dadaism has taken on the name “Marcel DuChamp—and, like Quichotte himself, an estranged sister who is dying in London. Beyond this, of course, there is another presence that DuChamp senses, the presence of his own creator, whom he believes is God but we know is Rushdie. But from Sancho to Quichotte to DuChamp to Rushdie to God the novel swallows its own tail in a hall-of-mirrors construction that only tends to emphasize a world where truth is a matter of opinion. Fentanyl plays a significant part in both stories as Rushdie takes on the opioid crisis, as he takes on American gun culture and an unnamed president “who looks like a Christmas ham and talks like Chucky,” a “wholly imaginary chief executive who was obsessed by cable news, who pandered to a white supremacist base.”

I’ve hardly scratched the surface of this multi-faceted novel, which swells to incorporate not only the story of Don Quixote but also that of Pinocchio(complete with Jiminy Cricket and the Blue Fairy), Eugene Ionesco’s Rhinoceros (with Mastodons taking the place of Rhinoceroses), and the favorite science-fiction theme of parallel universes. The book is a rollicking good time, even though it deals largely with devastating sorrow and disaster. Rushdie employs what Barth and Pynchon—and Heller and Vonnegut—chose to employ a generation ago: black humor in the face of an absurd world.

I do think this is a four Shakespeare book.

NOW AVAILABLE:

“The Knight of the Cart,” fifth novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at https://encirclepub.com/product/theknightofthecart/

You can also order from Amazon at

https://www.amazon.com/Knight-Cart-MERLIN-MYS…/…/ref=sr_1_1…

OR an electronic version from Barnes and Noble at

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-knight-of-…/1133349679…

Here’s what the book is about:

The embittered Sir Meliagaunt is overlooked by King Arthur when a group of new knights, including Gildas of Cornwall, are appointed to the Round Table. In an ill-conceived attempt to catch Arthur’s notice, Meliagaunt kidnaps Queen Guinevere and much of her household from a spring picnic and carries them off to his fortified castle of Gorre, hoping to force one of Arthur’s greatest knights to fight him in order to rescue the queen. Sir Lancelot follows the kidnappers, and when his horse is shot from under him, he risks his reputation when he pursues them in a cart used for transporting prisoners. But after Meliagaunt accuses the queen of adultery and demands a trial by combat to prove his charge, Lancelot, too, disappears, and Merlin and the newly-knighted Sir Gildas are called into action to find Lancelot and bring him back to Camelot in time to save the queen from the stake. Now Gildas finds himself locked in a life-and-death battle to save Lancelot and the young girl Guinevere has chosen for his bride.