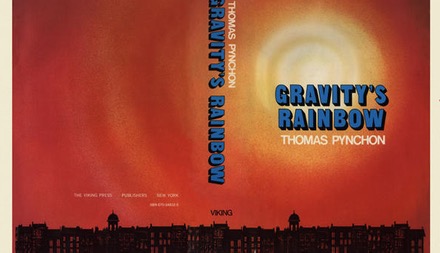

Gravity’s Rainbow

Thomas Pynchon (1973)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Susanns.jpg’ attachment=’78’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=10” appearance=’on-hover’]

2 JACQUELINE SUSANNS

[/av_image]

I was familiar with Thomas Pynchon from having written a senior honors thesis as an undergraduate in 1972 on what writers in those days were calling “the absurd novel.” Alhough I focused on John Barth at the time, I was considering the contributions of Heller and Vonnegut as well, and had struggled through V.and been impressed by the very readable and clever Crying ofLot 49, so when Pynchon’s third novel came out in 1973, I really had to buy a copy of it.

But it was long—nearly 900 pages in the paperback edition I’d procured. And I was busy in the early stages of graduate school. So despite the hyperbolic initial reviews of the book—“If I were banished to the moon tomorrow and could take only five books along, this would have to be one of them,” wrote the New York Times reviewer, and from the Saturday Review, “At thirty-six, Pynchon has established himself as a novelist of major historical importance”—I let it linger on my bookshelf unattended for months. And as I heard of the frustrations of exasperated readers, and as the necessities and responsibilities of life kept mounting around me, those months turned into years and that great brick of a tome continued to sit on my shelf unopened for 46 years. But with some of the free time granted me by retirement, I recently took the plunge, picked up the book and actually read it.

Certainly the book’s reputation has not retained its stratospheric heights in the intervening four and a half decades. While it’s true that the book is included in Timemagazine’s famous list of the 100 greatest English-language novels published since 1923 (where it checks in at No. 39, right after The Grapes of Wrath and right before The Great Gatsby), it does not have the kind of widespread devotion that those novels have. And while it certainly has the reputation for being a very long, complex, and difficult read—as, for example, Ulysses or Moby–Dick have—there are far fewer readers who would claim Pynchon’s book is ultimately as rewarding as those. Even in the year after its publication, a year in which it won the National Book Award, it was selected by the 1974 Pulitzer Prize committee to receive the award in fiction, but the selection was vetoed by the Pulitzer advisory board, who were reported to have found the novel “overwritten,” “turgid,” “obscene” in some parts, and overall “unreadable.” No Pulitzer for fiction was awarded that year.

Those remain the reactions of many of the novel’s readers, or perhaps I should say attempted readers. The book still has its staunch defenders, but the divided judgments of the Pulitzer group remain to this day. There is even a Website called “The 50 Best One-Star Amazon Reviews of Thomas Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow” where you can read things like “I’m convinced this book could be an interesting 100 page novel if all the excess verbiage were excised” (Overwritten? Check.); “I’ve tried three times to read this book. The farthest I’ve got is about page 20. As I read, my mind drifts to other things” (Turgid? Yup.); “It is the rambling of some intellectual who is just trying to impress you with obscure references or shock you with descriptions of degenerate acts” (Obscene? Okay.”); and finally, “Life’s too short,” and “I finally threw it against the wall in disgust” (Unreadable? Apparently.).

Still, the book is considered by many to be the quintessential postmodern novel, and to be fair, perhaps it is simply the “postmodern” aspect of the novel that many other readers react negatively to. But those same readers do not react this way to Catch-22 or Slaughterhouse-Five or the nearly-as-long Sot-Weed Factor or even The Crying of Lot 49. Milton talked about a “fit audience, though few” for his difficult epic Paradise Lost. Perhaps Pynchon had a similar limited audience in mind. The question to ask about Gravity’s Rainbow, then, may be, who is the intended audience?

For Gravity’s Rainbow has its defenders, of course. Chiefly they seem to admire its complexity (its sweeping encyclopedic scope and intricately wrought structure) and its tone (humorously irreverent and often scatological). The action focuses on Tyrone Slothrop, an American officer who, stationed in Britain late in the Second World War, comes under the scrutiny of British intelligence when it is discovered that the locations at which he has experienced erections with women in London correspond uncannily with areas of London struck by German V-2 missiles. The deeply paranoid Slothrop begins a quest that leads him across Europe in the last months of the war, searching for the location of, and the story behind, an ultimate rocket with the serial number 00000. The novel is divided into four major sections, each with a number of individual episodes separated by small squares, which some have likened to sprockets in a reel of film, since it could be said that Pynchon has emulated the structure of film in constructing the novel.

Slothrop becomes a picaresque character making his paranoid way through episode after episode, crossing paths with a Captain Blicero (a.k.a. Wiessmann), S.S. officer and rocket scientist; with a Dutch double-agent named Katje Borgesius with whom he has an affair; with the Soviet intelligence officer Vaslav Tchitcherine, who is on a quest to find his half-brother Enzian on whom he has vowed vengeance; with Enzian himself, who is commander of an all-African Schwarcommando company and has had an affair with Blicero; with silent film star Greta Erdman who is mentally unbalanced and addicted to masochistic sex; with the racist American Major Marvin Marvy, who is teamed with General Electric and trying to get access to German rocket technology and trying, at the same time, to eliminate Slothrop. One of the funnier scenes in the book is Slothrop hitting Major Marvy in the face with a pie thrown from a hot air balloon in which he is fleeing Marvy’s pursuing airplane.

But overall, as far as plot goes, there simply is no coherent plot in the sense that readers usually look for in a novel, but merely a set of vaguely related incidents with numerous sub-plots going off on tangents, and no real resolution to any of them—just for one example (and this may be a spoiler in the usual sense, though I’m not sure the term even applies here), when Tchitcherine does at last meet his brother Enzian, nothing happens and they don’t recognize one another. So you don’t read this book for an absorbing plot.

There are a number of themes of note, including, first, the idea that nobody in a position of power is to be trusted (this book did come out during the Watergate scandal, after all): just because you’re paranoid, it doesn’t mean they aren’t out to get you . A second theme is the idea that technology has altered our society irreversibly and can be either a blessing or a curse—the rocket, for example, may take man to the moon (as it had begun to at the time of the novel’s first appearance) or it may carry an atomic missile like the one that destroyed Hiroshima at the end of the war, and which seems to lie behind the world-shattering rainbow vision Slothrop experiences at the climax of his story.

After this point, Slothrop becomes “scattered”—he seems not to be a united personality at all any more. And that’s just the epitome of the fact that you also don’t read this book for its memorable characterizations. The fact is there are some 400 characters in this 400,000 word novel, and you will never keep them all straight. Additionally, they are never introduced in any traditional manner, but simply dropped on us at the beginning of a chapter in which we are suddenly immersed in a crowded scene with no roadmap, something like the beginning of a scene in a movie. Sometimes we don’t even know what character is being talked about. Here, for example, is an effective use of this technique in the introduction of a scene from part one:

In silence, hidden from her, the camera follows as she moves deliberately longlegged about the rooms, an adolescent wideness and hunching to the shoulders, her hair not bluntly Dutch at all, but secured in a modish upsweep with an old, tarnished silver crown, yesterday’s new perm leaving her very blonde hair frozen on top in a hundred vertices, shining through the dark filigree.

But at its worst, Pynchon’s style can be bewildering and, as one of the one-star reviews above noted, can make your mind wander to other things before you get to the end of a sentence:

Whitecaps will come slamming in out of the darkness, and break high over the bow, and brine stream from the golden jackal mouth… Count Wafna lurch aft in nothing but his white bow tie, hands full of red, white, and blue chips that spill and clatter on deck, and he’ll never cash them in… the Countess Bibescue dreaming by the fo’c’sle of Bucharest four years ago, the January terror, the Iron Guard on the radio screaming Long Live Death, and the bodies of Jews and Leftists hung on the hooks of the city slaughter-houses, dripping on the boards smelling of meat and hide, having her breasts sucked by a boy of 6 or 7 in a velvet Fauntleroy suit, their wet hair flowing together indistinguishable as their moans now, will vanish inside sudden whiteness exploding over the bow… and stockings ladder, and silk frocks over rayon slips make swarming moires… hardons go limp without warning, bone buttons shake in terror… lights be thrown on again and the deck become a blinding mirror… and not too long after this, Slothrop will think he sees her, think he has found Bianca again-dark eyelashes plastered shut and face running with rain, he will see her lose her footing on the slimy deck, just as the Anubis starts a hard roll to port, and even at this stage of things-even in his distance-he will lunge after her without thinking much, slip himself as she vanishes under the chalky lifelines and gone, stagger trying to get back but be hit too soon in the kidneys and be flipped that easy over the side and it’s adios to the Anubis and all its screaming Fascist cargo, already no more ship, not even black sky as the rain drives down his falling eyes now in quick needlestrokes, and he hits, without a call for help, just a meek tearful oh fuck, tears that will add nothing to the whipped white desolation that passes for the Oder Haff tonight…

Now then: tell me please what is the subject of that sentence?

My point is, readers who are looking for a narrative with a strong plot, relatable characters, and rendered in lucid, articulate prose will be put off by Gravity’s Rainbow. If you believe in the absurdity of the universe (The universe is meaningless; If the universe has any meaning, it cannot be known; If any meaning can be known, it cannot be expressed in language), then you may appreciate Gravity’s Rainbow as the perfect marriage of form and content. For myself, I’m glad to have finally read the book, but I won’t be re-reading it any time soon. At least not for another 46 years.

Two Jacqueline Susanns for this one.

NOW AVAILABLE:

“The Knight of the Cart,” fifth novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at https://encirclepub.com/product/theknightofthecart/

You can also order from Amazon at

https://www.amazon.com/Knight-Cart-MERLIN-MYS…/…/ref=sr_1_1…

OR an electronic version from Barnes and Noble at

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-knight-of-…/1133349679…

Here’s what the book is about:

The embittered Sir Meliagaunt is overlooked by King Arthur when a group of new knights, including Gildas of Cornwall, are appointed to the Round Table. In an ill-conceived attempt to catch Arthur’s notice, Meliagaunt kidnaps Queen Guinevere and much of her household from a spring picnic and carries them off to his fortified castle of Gorre, hoping to force one of Arthur’s greatest knights to fight him in order to rescue the queen. Sir Lancelot follows the kidnappers, and when his horse is shot from under him, he risks his reputation when he pursues them in a cart used for transporting prisoners. But after Meliagaunt accuses the queen of adultery and demands a trial by combat to prove his charge, Lancelot, too, disappears, and Merlin and the newly-knighted Sir Gildas are called into action to find Lancelot and bring him back to Camelot in time to save the queen from the stake. Now Gildas finds himself locked in a life-and-death battle to save Lancelot and the young girl Guinevere has chosen for his bride.