Tramadol Online Cod 180 Sometimes travel can be pleasingly serendipitous, as it was for us when we traveled to West Yorkshire, to the town of Hebden Bridge, on the trail of my wife’s favorite, Sylvia Plath, and her husband, Ted Hughes. We soon discovered we were in fact a scant eight miles from the town of Haworth—where, it turns out, Emily, Charlotte, and Anne Brontë lived in their father’s parsonage for nearly their entire lives, and where they wrote Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, and the rest of their body of work. The Brontë Parsonage Museum (run by the Brontë Society, one of the oldest literary societies in the world devoted to English-language writers), is visited by more than 100,000 Brontë lovers each year. Who knew?

The easiest—and least expensive—way to get to Haworth from Hebden Bridge is by bus: The local Keighley Bus Company runs their B3 Bus, commonly known as the “Brontë Bus,” from the town of Keighley to the town of Hebden Bridge once every hour, then back again. The drive is pleasant, and allows you to take in the landscape of heather and moors that inspired the settings of the sisters’ novels. From Hebden Bridge, the bus makes several stops in Oxenhope and then in Haworth. But beware: The jumping off point is not easily recognized from the bus, and Haworth itself does not have a lot of signs directing you to the museum. We ended up going at least a mile too far, and saw one sign for the museum with an arrow pointing back in the direction we’d come from. After a long walk in which Google and Siri both helped but little, we got back to the Haworth train station, and realized we had to hike up a fairly steep hill to get to the “Bronte Village,” wherein we finally found the parsonage. I guess the other 99,998 visitors to Haworth are a lot smarter than we were, because they seemed to have no trouble finding the place. Here’s a tip: If you’re riding the “Brontë Bus,” get off at the stop by the quaint-looking Haworth Old Hall Inn, no matter what Siri tells you to do.

The parsonage itself is a handsome Georgian house, built in 1778-79 for the rector of St. Michael’s and All Angels’ Church, and it became the home of the Brontë family when their father, Patrick, was appointed incumbent of the parish (that is, a pastor with a lifetime appointment). As one tours the house and reads the informative placards, the story of the family unfolds. Patrick and Maria Brontë moved into the house with their six children in April 1820. They had been living six miles away in Thornton, where Patrick had been serving that parish and where Charlotte (4), Emily (2), and the infant Anne had been born as had their 3-year-old brother, Branwell. Tragedy struck the family quite soon, as Maria died of cancer in 1821, and the two oldest sisters, Maria and Elizabeth, fell ill while attending a boarding school for the daughters of clergymen, dying within a month of one another in 1825.

But one sees in the house the rooms in which the remaining children played and created imaginative adventure stories set in fantasy lands of their own invention, led by Branwell and Charlotte. We form an impression of the brilliant but troubled Branwell, writer and artist, whose painting of the three sisters hangs in the National Gallery but is hung in facsimile in the parsonage—and we see the room where he died of consumption, addicted to alcohol and drugs, at the age of 31.

We see the room where the adult sisters shared their literary efforts published under the male pseudonyms with their own initials: Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell. We learn about their ill-fated plan to run a school together and the funding of their trip to Brussels to learn the craft of teaching as it was practiced in their day (know your French!). And we see the couch on which Emily died of consumption at the age of 30. We also learn how Anne, ravaged with the same disease that killed Emily, traveled to Scarborough in hopes that the air there would be beneficial. She died just a few days after their arrival in May 1849, and Charlotte buried her there, dead at the age of 29.

And we learn how the final surviving sister married her father’s curate Arthur Bell Nicholls at her father’s church in 1854 after publishing her final novel, but then died herself in the early stages of pregnancy in March 1855, three weeks before her 39th birthday. Her death certificate gave the cause of death as consumption again, but it’s currently believed that she died of malnourishment and dehydration brought on by a severe form of “morning sickness” now diagnosed as hyperemesis gravidarum.

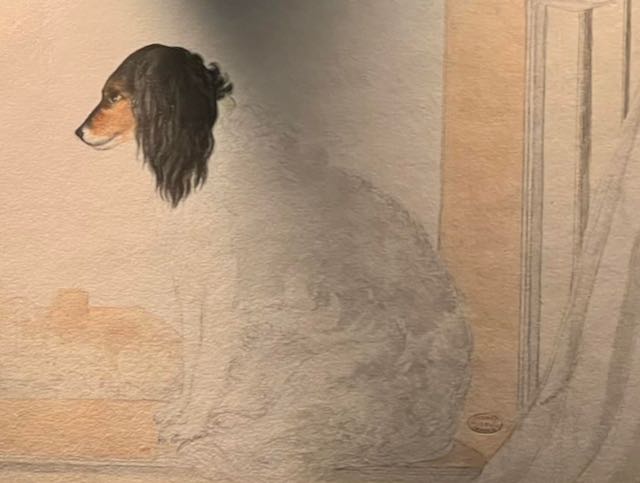

More than simply telling their story, the museum makes it possible for you as visitor to be in the room where it happened—not only the table where the sisters wrote and the couch where Emily died, but there are toys and shawls and bonnets and furniture and other artifacts that reinforce the material environment of the Brontës. Among my favorites were Charlotte’s wedding gown and a letter written by Patrick Brontë to his daughter Charlotte, signed by “Old Flossie,” the family dog. There’s even a portrait of Flossie done by Charlotte herself.

Since all contents of the parsonage were auctioned off when Patrick died in 1861, much credit must be given the Brontë society who through a mammoth effort were able to collect and preserve a significant number of artifacts in the 1890s and to start a museum. When Haworth industrialist Sir James Roberts purchased the parsonage in 1928 and donated it to the Bronte Society to house their museum, the present memorial was born.

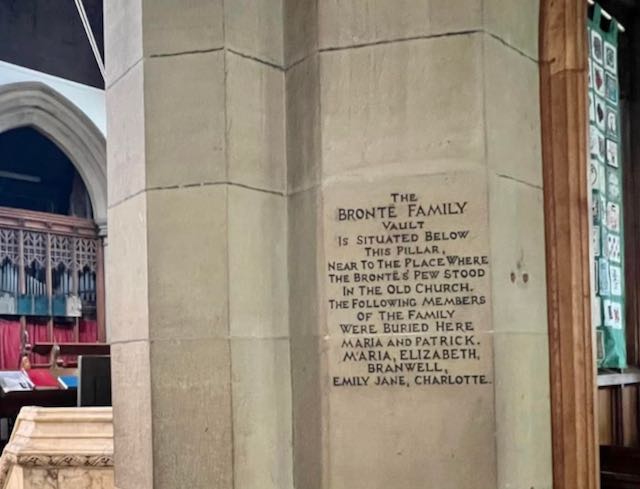

This is a must-see place for Brontë lovers. If you go, don’t forget to visit the church next door. It’s been rebuilt since Patrick’s time, but the new church has a plaque marking where the remains of the Brontë family members lie below the floor. Or you can wander through the old churchyard and listen to the wind gusting over the moor. You might imagine you hear Heathcliff himself calling.