by Stacey Margaret Jones

Come for the Platinum Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth and stay for the greatest American poet of the 20th century. That was my guiding principle on our June trip to the United Kingdom, where we arrived to see the Trooping of the Colour (and get great photos of the Cambridge kids as they carriaged past us on the Mall) on June 2. We made the most of our jet lag to get up at 4:30 a.m. and stake out a spot in St. James’s Park by 6:15.

But first things first, and that means that on Wednesday, June 1, after landing and depositing our luggage at our AirBnB in Notting Hill (and enjoying pizza and prosecco at Harrod’s in Knightsbridge), we put our newly acquired unlimited-Tube-rides-for-a-week Oyster Cards to work and headed to Primrose Hill in search of Plath’s life in London.

I have always been drawn to Plath. Reading a biography of her in 1991 after graduating with my elementary education degree, I saw we had a lot in common, and I felt seen and heard reading of her own depression and related struggles in her early adulthood. And in 1994, on my first trip to London, I’d hunted for her apartment on Fitzroy Road, but before smart phones and Mapquest, my brother and I had trouble being sure we were in the right place. The photo I have of me in my pleated Eddie Bauer chinos and chambray shirt from that summer shows me looking grim, not really because I may have been standing in front of the apartment where she killed herself during a horrible winter in 1963, but because I was pretty sure I wasn’t standing in front of her apartment at all, and I was out time and opportunity (too many Fitzroy-type street names in the area and no way to find the right one).

My disappointment was proportional to my respect and admiration for her technical ability as a poet and her persistence as a writer, famously sending out her work from a young age and putting it right back in the mail to another outlet when it was rejected until in her early 30s, she had earned a first-look contract with the New Yorker. As a poet myself, I was ready to learn what Plath had to teach. Then, in January 2022, I read Heather Clark’s stellar Red Comet, a comprehensive literary biography of Plath that reinspired me to find the English sites from Plath’s life in the country after she met and married British poet Ted Hughes when her Fulbright scholarship study brought her to England in the 1950s.

And thanks to Clark, Google and Siri’s maps, this time I had the tools to find everything for sure. In London, there were several possibilities, including the church where she and Hughes were married in 1956, but I was focused on Primrose Hill in Northeast London (adjacent to trendy, hipster Camden), where Plath and Hughes lived in a flat on Chalcot Square when they returned to London in 1959 after living in Massachusetts. They were living here when their daughter was born and when Plath’s first collection of poetry, The Colossus was published. There is a blue plaque on the house to mark Plath’s residence here (but not marking Hughes’). From here they moved to Devonshire, where their son Nicholas was born, and their marriage broke down.

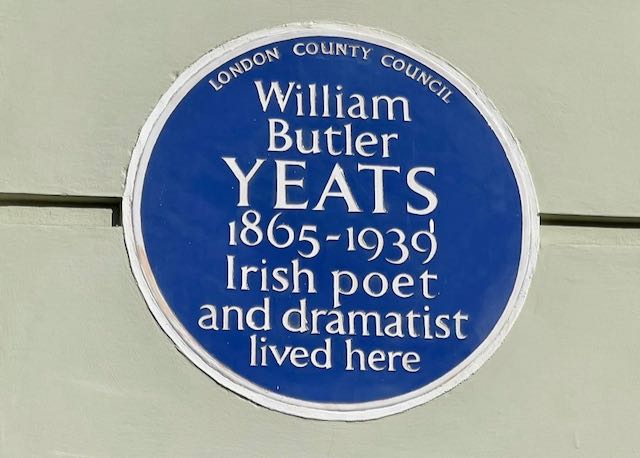

Plath returned to London in October 1962 alone with her small children and took a five-year lease on a two-story flat at 23 Fitzroy Road, just a few blocks from the previous Chalcot Square apartment. She was obsessed with getting the apartment because Yeats had lived in the building, which was marked by a blue historical plaque with Yeats’ name (and still is, with no mention of Plath). It was in this apartment where she died by suicide in February 1963 after blocking the children’s room door with clothes and towels, turning on the gas in the kitchen below and lying down with her head inside.

I was a bit anxious on the hunt for her residences because of my previous experiences, so I was distracted by the emotions of the search. And I climbed the steps of the Fitzroy Road house for the photo with a slight sense of accomplishment. But as I turned for the picture, a heavy and intense feeling of loss and profound grief settled on me unexpectedly, and if the photo had been a close-up, my tears would be evident. It’s rare for me to feel that much environmental sadness, especially on a London Street going about its daily life, but it was nearly crushing. I gathered myself down at the local, the Princess of Wales pub, where I stopped crying and imagined Sylvia Plath living in the neighborhood, both as a young poet, wife and mother, and then later on, exhilarated when she got the Yeats flat and lived out the end of her life, which became the most productive time of her writing life when she produced the poems she is best known for.

After the “Platty Jubes” was over, we were on our way to Edinburgh, with some literary stop-overs scheduled including Hebden Bridge/Heptonstall in West Yorkshire. While this remote area was the birthplace of Plath’s husband, Poet Laureate Ted Hughes, it is also the place Plath lies in death. Devastated and in shock at her suicide, Hughes, who was still married to the poet even though they’d separated over his affair with Assia Wevill, buried his wife in the family plot in Heptonstall. This is a small West Yorkshire village at the top of a big hill adjacent to the bigger town of Hebden Bridge at the foot of the hill.

When we were planning the trip and I realized I could make time for the trip to her grave, I told my cooperative husband that I knew nothing about Heptonstall and Hebden Bridge, and that we were going there to stay for two nights regardless of what they were like as vacation towns. “They could,” I cautioned, “be horrible, black little places left scarred and destroyed by the end of the mining economy in the late twentieth century.” We had no idea we were going to such a lovely, tourist-friendly, artsy area, a place I not only loved visiting but a destination I decided I never wanted to leave.

We arrived in Hebden Bridge on a Wednesday morning from Nottingham and pulled our luggage up and down the hills of the town on the short walk (made longer by the inclines) to the White Lion Inn, the oldest building in the incredibly picturesque town of grey and blackening Yorkshire stone houses and shops. We crossed the Rochdale canal with its impossibly quaint canal boats lined up along the quay. After storing our luggage, eating a perfect lunch in the snuggliest pub imaginable and taking a bit of a lie-in to rest up, we realized the lack of rain when it seemed it was always forecast for the next day meant it was time to walk to Heptonstall and find the cemetery and grave.

When you go, be prepared for a MAJOR hill. Later, my FitBit registered this climb as equivalent to fifty flights of stairs. Fifty. Up a cobblestone lane, stone steps through shady hillsides (I saw a guy walking along, turn and seem to disappear right into the long grass and woodland, and then noticed my navigation was directing me to do the same… hidden there was a well-worn path with stone stairs and handrails when necessary). Once you’re in Heptonstall, you’ll stroll uphill through even more picturesque streets of storybook houses with blooming flower baskets, window boxes and climbing vines to the falling down church St. Thomas a Beckett. Though Plath wrote this line of Grantchester Meadows near Cambridge, I couldn’t stop thinking of her lines about “a country on a nursery plate” where “nothing is big or far.”

Next door in the village’s church-in-use St. Thomas the Apostle, is a walled cemetery in the church yard, secretive and shaded, with delipidated graves with hard-to-read headstones, mossy and dulled by time and the weather high up in the moors. Beyond that was a small, flat open field with more graves much more organized on a grid, but, for a few minutes, no more yielding of their information as we searched for Plath’s plot. There are no signs directing pilgrims, so we took off separately to go down each row in the late afternoon, high up on this Yorkshire hill on a June day, when the wind was cool enough to call for sweaters and jeans. I got impatient and googled, finding a Find-A-Grave website that pinpointed the exact spot in Google maps, which is how I found it behind a large, lovely columbine bush waving to me in the Yorkshire wind.

Again, my focus on logistics was pushed away by the descent upon me of such a heavy, holding sadness, I stood and blinked away tears as I pulled out the Flair pen I’d brought to leave for her (they are my favorite writing utensil). My husband asked why her last name, Hughes, was so strangely blanked out… it’s still completely visible, as if someone had used a kind of white-out on stone that is not exactly the right color, but they didn’t mind because the point was to show the removal of it, not to remove it at all. I told him how many Plath lovers felt such anger toward Hughes over the breakdown of their marriage that they resented his name on her stone and scratched it out, or this was the theory. The grave even went unmarked for a long time because the family couldn’t keep up with the vandalism. But “Hughes” is faintly back and the stone is there. It reads, “In Memory / Sylvia Plath Hughes / 1932 – 1963 / Even Amidst Fierce Flames / The Golden Lotus Can Be Planted.”

I stayed awhile, holding my emotions gently, looking around, taking in the sky, the air, the light, the bees buzzing in the columbine bushes, the remote quiet, the church ruins, considering how we had spent considerable time and money to find ourselves in a tiny Yorkshire town at the top of a hill, alone with the grave of a poet, and I felt both the sorrow and loss of her death as well as gratitude for the opportunity to make the pilgrimage and even more for the circumstances that meant she would be buried in such an unlikely but stunning place for the life she lived—not in Massachusetts where she was born and lived until graduate school, not in London where she began making a name for herself as a poet, got married, became a mother, and then lived on her own when her marriage broke down, not in Devonshire, where she lived with her husband and children as a family and established the writing routines that led to the London period of productivity, but on a remote moor in West Yorkshire, where you can hear almost exclusively the wind across the top of the hill and in the trees, some distant voices of passersby on the cobblestone road, feel the northern light of the sun, the exhaustion of a long journey over and the reaching shadow of the seemingly eternal church tower ruins. This cannot do anything but evoke lines from Plath’s poem, “The Moon and the Yew Tree”:

I have fallen a long way. Clouds are flowering

Blue and mystical over the face of the stars.

Inside the church, the saints will be all blue,

Floating on their delicate feet over cold pews,

Their hands and faces stiff with holiness.

The moon sees nothing of this. She is bald and wild.

And the message of the yew tree is blackness-

blackness and silence.

How interesting. I didn’t know much about Sylvia Plath, but your post has inspired me to now know more. Lovely description of the village. I can quite imagine it.

As somebody who lives in Heptonstall and walks through the cemetery with my dog every day this has been lovely to read. I’m glad you enjoyed Hebden and Heptonstall they are very special places.