Mank

David Fincher (2020)

Facts for You:

Where to Watch: Streaming on Netflix

Length:2 hours, 12 minutes

Rated: R for language

Names You Might Know: Gary Oldman,Amanda Seyfried, Charles Dance, Lily Collins

He Said: “You cannot capture a man’s entire life in two hours, you can only hope to leave the impression of one,” says Herman J. Mankiewicz (Gary Oldman), title character of David Fincher’s new self-consciously meta-film Mank: He is explaining the narrative structure of his screenplay for Citizen Kane—the glimpses we get of Kane’s life from multiple points of view.

Anyone with even a passing interest in the history of film knows the huge place that Orson Welles’ masterpiece Citizen Kane holds in that history. It held the top spot on AFI’s original list of the “100 Greatest American Films,” and held that spot again on the revised AFI list ten years later. Fincher (an Oscar-nominee for both The Social Network and The Curious Case of Benjamin Button) has very consciously emulated that nonlinear storytelling technique in Mank, which ostensibly takes place in 1940 in an isolated farmhouse rented by Welles (Tom Burke of TV’s C.B. Strike) where Mank, immobilized by a half-body cast after a car accident, has 60 days to write a script for Welles’ new film. But a series of flashbacks give us glimpses of Mank as MGM studio hack, and of his rocky relationships with studio head L.B. Mayer (Arliss Howard of Moneyball) and production head Irving Thalberg (Ferdinand Kingsley of TV’s Victoria), and also with media mogul William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance of Game of Thrones) and his mistress, the comic actress Marion Davies (an absolutely brilliant Amanda Seyfried, of Mama Mia: Here WeGo Again). Among other things, these flashbacks demonstrate Mankiewicz’s motivations for his thinly-veiled skewering of Hearst in the character of his screenplay’s protagonist, Charles Foster Kane.

But the film, in glorious black and white, emulates Kane in so many other ways—its use of deep-focus photography (if you notice such things), its referencing of famous Kane scenes (such as the scene when Kane comes into the room in which Susan Alexander has tried to kill herself) which are only likely to make an impression on viewers fairly well acquainted with Kane—I wonder if non-Kane fans will take much away from this movie?

She Said: I agreed to watch this for my Kane-loving husband as what I figured would be a “good-for-you” movie. I would be edified, I would learn and grow, but I might be scrolling Instagram some throughout it as well. While I respect Citizen Kane and understand what an influential film it is, I don’t have affection for it. I’m not emotionally engaged by it, so I don’t feel the payoffs the film grants those who are. I figured I’d feel the same way about this movie as I do about its origins.

At the same time, I freaking love Gary Oldman. LOVE. It’s love. If you scanned my brain while showing me photos of various things, an orange, chocolate cake, Antarctica, etc., when you show me a photo of my iPhone or a photo of Gary Oldman, the love centers will light up. He absolutely disappears into a role, because every cell in his body shows up to work on set, ready to perform. I was pretty fresh off being displeased by Emily in Paris, so I had some negative emotions about Lily Collins (I won’t get too granular in naming those feelings), but she is good as Mank’s nurse, though her subplot as wife of an MIA British airman is manipulative and ineffective, she’s fine. I agree with He Said that Amanda Seyfried is luminous, even in black and white (which not all of us find glorious), as Marion Davies. When she’s on screen, even opposite my beloved Oldman, I only have eyes for her.

I enjoyed the Hollywood history aspects of this film, and I was right that I would learn and grow watching it. And I think the choice to shoot in black and white is fitting because it’s an origin story and also a big allusion to Kane that Kaneophiles (not me) will find lighting up their Kane-loving emotional brain centers. (Not mine, though.)

He Said: Yeah, that’s what I was afraid of. There is yet another Kane-related aspect of this film that most certainly will escape non-Kaneites: The script, written by Fincher’s late father back in the ’90s, was based largely on a lengthy New Yorker article published back in 1971 by critic Pauline Kael called “Raising Kane,” in which she revived the original controversy over the authorship of the Oscar-winning screenplay, arguing that Mankiewiczshould get sole credit for the writing. The film does make it clear that Mank originally agreed to ghost-write the film for Welles (Welles’ contract with RKO required him to write, produce, direct and star in two films for the studio, so he had to be credited as writer of the movie). But that is not the main thrust of the film. It seems to me that the film is really about the writing process, and all the experiences and relationships that are transformed by the writer into art. Mank’s relationship with Davies is really the heart of this movie, and there is not a little shame in the film that Mank uses this relationship to create the character of Kane’s untalented and unappreciated second wife, Susan Alexander. Do you think that’s the real theme here? As a sidelight, I just want to add that I was tickled by the awesome cameo of Bill Nye the Science Guy as writer and gubernatorial candidate Upton Sinclair).

She Said: You bring up something I meant to address in my initial pass: I did really enjoy the writing-life aspects of the film very much. I don’t know if I experienced the Mank-Davies relationship as the heart of the film because, while I really enjoyed those scenes and could see there was something lovely between them, it wasn’t quite developed enough for me, BUT what was developed enough to engage me emotionally the most was the depiction of the writer’s life and what the writer processes into art. Thank you for reminding me of that, because it’s subtle, but to me that was the big payoff of the film.

He Said: Right. So, speaking of writing, the film implies (even directly states in a closing textual note) that Citizen Kane was Mankiewicz’s last hurrah, that he didn’t do much afterwards. So the film is kind of presented as the fading, alcoholic writer’s climactic final gasp, through which he attains immortality. The fact is, Mank was nominated for another Oscar the following year for his screenplay for Pride of the Yankees, the classic Lou Gehrig biography. And he wrote several more screenplays, including, ten years later, another baseball movie, Pride of St Louis (the Dizzy Dean story). But anyway, in the end, I loved the movie, loved the retro- and meta-qualities of it, loved the story and loved the performances, especially of Oldman and Seyfried, both of whom, I predict, will be nominated for Academy Awards, for Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress, respectively. (Hollywood, after all, loves to honor movies about Hollywood). I say we give this movie four Hitchcocks.

She Said: I’ll give it three Soderberghs; It’s pretty good at what it’s good for, but you helped me realize that a) the emotional heart of the Davies-Mank relationship could have been more pronounced and 2) the fact-skewing of the ending is annoying and unnecessary.

This Week’s We Watched It So You Don’t Have To:

She Said: Paranoidon Netflix.

Hot Take:Ridiculously written cliff-hangers in an interesting mystery featuring mostly unlikeable to detestable characters.

NOW AVAILABLE:

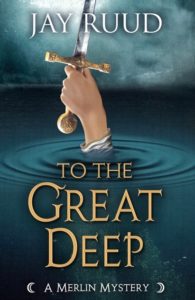

To the Great Deep, the sixth and final novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at http://encirclepub.com/product/to-the-great-deep/

You can also order from Amazon (a Kindle edition is available) at https://www.amazon.com/Jay-Ruud/e/B001JS9L1Q?ref=sr_ntt_srch_lnk_1&qid=1594229242&sr=8-1

Here’s what the book is about:

When Sir Agravain leads a dozen knights to arrest Lancelot in the queen’s chamber, he kills them all in his own defense-all except the villainous Mordred, who pushes the king to make war on the escaped Lancelot, and to burn the queen for treason. On the morning of the queen’s execution, Lancelot leads an army of his supporters to scatter King Arthur’s knights and rescue Guinevere from the flames, leaving several of Arthur’s knights dead in their wake, including Sir Gawain’s favorite brother Gareth. Gawain, chief of what is left of the Round Table knights, insists that the king besiege Lancelot and Guinevere at the castle of Joyous Gard, goading Lancelot to come and fight him in single combat.

However, Merlin, examining the bodies on the battlefield, realizes that Gareth and three other knights were killed not by Lancelot’s mounted army but by someone on the ground who attacked them from behind during the melee. Once again it is up to Merlin and Gildas to find the real killer of Sir Gareth before Arthur’s reign is brought down completely by the warring knights, and by the machinations of Mordred, who has been left behind to rule in the king’s stead.