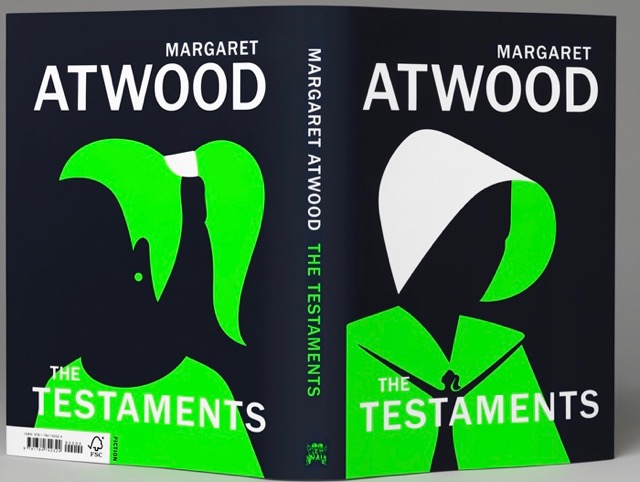

The Testaments

Margaret Atwood (2019)

[av_image src=’http://jayruud.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Shakespeare-180×180.jpg’ attachment=’76’ attachment_size=’square’ align=’left’ animation=’left-to-right’ link=” target=” styling=” caption=’yes’ font_size=” appearance=’on-hover’]

Ruud Rating

4 Shakespeares

[/av_image]

Unless you’ve been living in a cave the past few months, you are probably aware that TheTestaments, Margaret Atwood’s long-awaited sequel to TheHandmaid’sTale, was released on September 10 and, a month later on October 14, shared the prestigious Man Booker Prize (which Atwood had previously won in 2000 for The Blind Assassin). It was a strange feeling to be reading the book at the very time it received the award, and naturally colored my reading of it, forcing me to wonder all the while I was reading it whether it was deserving.

The Testaments is a sequel that’s been a long time coming. It’s been 34 years since the release of The Handmaid’s Tale, a novel Atwood wrote in 1984 conscious, I’m sure, of the echoes of Orwell’s dystopian novel of that name ringing in her ears. But the popular and critical success of the Hulu TV series based on that novel was certainly incentive to produce this sequel. The TV series found in the now classic novel a way to make a statement about women’s rights in particular, which had suffered significant setbacks under current political agendas, and tapped into a powerfully resistant vein that also made The Testaments’initial run of 500,000 copies not overly optimistic. Atwood worked with the series’ producers, ensuring that the new novel would not tread on the toes of further anticipated plotlines in the TV show.

In fact, the new novel deals with events that happen chiefly fifteen years or so after the conclusion of the first novel—though it also includes flashbacks that bring us back to the founding days of Gilead. By now you probably know that the story is told through three narrators—two of the narrative strands are labeled as testimony, as if in a criminal procedure, from two different teenaged girls. The third is from a secret personal journal kept by, of all people, Aunt Lydia, detailing a long and sordid history of Gilead from the inside, as witnessed by the chief enforcer in the women’s sphere of Gilead. She writes this memoir, she says, “for your edification, my unknown reader”—looking forward to a time, or anticipating a place, where such things may be spoken of openly.

That part may be something of a shock for the unprepared reader, and a certain revulsion must be overcome to get through those first pages. But the description of Aunt Lydia’s arrest and the psychological and physical tortures to which she is subjected—having been a dangerous “so-called woman judge” in the days before Gilead—are reminiscent of the methods of interrogation by Stalin’s secret police described in Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago (“Thanks to ideology,” Solzhenitsyn wrote, “the twentieth century was fated to experience evildoing on a scale calculated in the millions”—and there is no more dangerous ideology than the God-sanctioned self-righteous patriarchy that rules in Gilead). When Aunt Lydia relates the brutal suppression of what she calls “all that claptrap about life, liberty, democracy, and the rights of the individual I’d soaked up at law school,” it is only the least empathetic of readers who will condemn her submission. As Atwood herself said in a recent interview, “We all like to think we would have been heroic, but that’s probably not true.” It’s easy to say “I would have resisted” when it is not you on the rack.

The first of the younger witnesses (labeled Witness 369A) is a young woman named Agnes Jemima, who has been raised in Gilead by a Commander Kyle and his wife Tabitha, whom Agnes loves and thinks of as her mother but whom, she comes to realize, was only her adoptive mother. Agnes’s stepmother, Paula, whom the cold Commander Kyle marries shortly after his gentle first wife’s demise, wastes no time in trying to marry Agnes off to a Commander old enough to be her grandfather. Despite her training and grooming for this moment, Agnes is less than thrilled with the prospect, and also becomes curious about her birth mother. Having for years been unable to remember anything from her early years, she begins to have a “hazy memory of running through a forest with someone holding my hand.”

Our third witness (369B) is a young teenager named Daisy, growing up in freedom in Canada for whom Gilead is just a dysfunctional neighboring country run by a repressive regime she wants no part of. But her life isn’t perfect: Like Agnes she’s being raised by a couple, Doug and Melanie, who are nother parents, who run a thrift store somewhere off the beaten track in the Great White North. She declares that things never felt quite right with the couple: “It was like I was a prize cat they were cat-sitting,” and on her birthday she discovers she is simply a “fraud–a forgery done on purpose.” After a terrorist attack on the thrift store, she is spirited away and discovers that her real name is Nicole—yes, that Nicole. In her only real nod to the TV series, Atwood has given us a grown up “Baby Nicole,” the daughter of June/Offred smuggled into Canada, now fifteen years older (not really a spoiler—it’s revealed fairly early and you’ll suspect it long before that).

Atwood adds some new wrinkles to the Gilead setting that will pique your interest: There is the Rubies Premarital Preparatory school, a kind of Gilead version of Hogwarts, where adolescent girls are trained (brainwashed?) to be properly submissive wives to the Commanders who will enslave…uh, marry them. There’s an Underground Femaleroad that helps woke Handmaids to escape north into friendly Canada. There’s a Gilead “missionary” program called Pearl Girls, in which Aunts-in-training go two-by-two beyond Gilead’s borders, proselytizing for all the world like Mormon missionaries, but in their case trying to bring unsuspecting young girls into the Gilead cult, mainly to replace the Handmaids who are defecting.

And as the novel hurtles to its climax, the story becomes a kind of a girl-buddy story, with Agnes and Nicole on a dangerous road trip. Whether they are Thelma and Louise or Romy and Michelle I won’t reveal since that would be getting into the realm of spoiler. But I will say that, in contrast with The Handmaid’s Tale, The Testaments is more plot-driven, more of a page-turner.

And that is precisely what some reviewers have faulted the novel for: How can it possibly be Serious Literature if we are interested in how the plot comes out? Are we interested in the plot of Orwell’s 1984? Well, OK, bad example. What about the true classics, the foundations of Western literature like, say, Hamlet? No, bad example, say Sophocles’ Oedipus the King? Oh, never mind. I guess a plot is all right to have after all. Other reviewers didn’t like the fact that the three narrators, spread across the class strata of Gilead and seeping into neighboring Canada, made for such a broad stage, unlike the claustrophobic daily life of Offred, trapped in her little life in The Handmaid’s Tale. But the fact is, we’ve been there and done that. Why should Atwood repeat that kind of focus? Here, she wants to broaden her strokes and take in all of Gilead and its relations with the rest of the world. That is not a weakness but and expansion of the novel’s theme. Others see the protagonists’ youth as less interesting, since they don’t have the perspective of the maturity and varied sexual experiences of June. And while it’s true that at times the novel crosses into YA territory, that’s not in itself a weakness, since it makes the book into more of a Bildungsroman, a kind of initiation story, which may not be the kind of story those readers were looking for, but is perfectly legitimate and interesting in its own right. So essentially, the complaints I’ve seen really amount to something like “I don’t like this book because it’s not the book I would have written if I were writing this book.”

And thank God it’s not. I didn’t want to read the same book again, or see a printed version of the TV show. What we have in The Testaments is a beautiful book in its own right, one with characters you care about in a world that’s frighteningly real, engaged in a story whose outcome you look forward to discovering, and told by a true master of the English language. Shut up and give it a Booker Prize. And Four Shakespeares while you’re at it.

NOW AVAILABLE:

“The Knight of the Cart,” fifth novel in my Merlin Mysteries series, is now available from the publisher, Encircle Publishing, at https://encirclepub.com/product/theknightofthecart/

You can also order from Amazon at

https://www.amazon.com/Knight-Cart-MERLIN-MYS…/…/ref=sr_1_1…

OR an electronic version from Barnes and Noble at

https://www.barnesandnoble.com/w/the-knight-of-…/1133349679…

Here’s what the book is about:

The embittered Sir Meliagaunt is overlooked by King Arthur when a group of new knights, including Gildas of Cornwall, are appointed to the Round Table. In an ill-conceived attempt to catch Arthur’s notice, Meliagaunt kidnaps Queen Guinevere and much of her household from a spring picnic and carries them off to his fortified castle of Gorre, hoping to force one of Arthur’s greatest knights to fight him in order to rescue the queen. Sir Lancelot follows the kidnappers, and when his horse is shot from under him, he risks his reputation when he pursues them in a cart used for transporting prisoners. But after Meliagaunt accuses the queen of adultery and demands a trial by combat to prove his charge, Lancelot, too, disappears, and Merlin and the newly-knighted Sir Gildas are called into action to find Lancelot and bring him back to Camelot in time to save the queen from the stake. Now Gildas finds himself locked in a life-and-death battle to save Lancelot and the young girl Guinevere has chosen for his bride.